“Several existences are needed to make a sole person.” That’s why Philip I is confused with his grandson Philip II (who, in the novel, becomes his son); why Celestina traverses the centuries, and the wife of Philip II goes to England to become Queen Elizabeth. Characters from books — Don Juan and Don Quixote — join real characters, and at certain times the silhouettes get confused: Don Quixote becomes Don Juan and Don Juan becomes Don Quixote.

If Esch is Luther, the history which leads from Luther to Esch is simply a private story of Luther-Esch. The structural consequences are overwhelming. The novel has always been built on the notion of temporal space which couldn’t go beyond the dimensions of one life. To imagine a romanesque story lasting a thousand years or even a hundred would have seemed nonsensical.

And if Ludovico discovers in Mexico a new undiscovered continent, if he then finds himself in Palestine in Roman times, and if he appears during the last summer of our century, in Paris, with Celestina — she who was the mistress of Philip I and Philip II — the time of the novel becomes limitless. The private story of all these characters (reincarnated, immortal) is nothing more than the story of history itself.

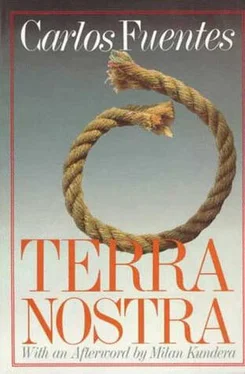

If Esch is Luther, the novel enters the realm of the “fantastic.” The fantastic of Terra Nostra is not far from madness, but that folly (baroque folly) does not oppose the novel as an aesthetic category. On the contrary, Terra Nostra is the spreading out of the novel, the exploration of its possibilities, the voyage to the edge of what only a novelist (“a Dostoevsky,” as Fuentes says) can see and say.

9

For Cervantes, history was the barely visible background of adventure.

For Balzac, it became a “natural” dimension without which man is unthinkable.

Today, at last, history appears like a monster, ready to assault each of us and to destroy the world. Or else (another aspect of its monstrousness), it represents the immeasurable, incomprehensible mass of the past — a past which is unbearable as forgetfulness (because man will lose himself), but also as memory (because its mass will crush us).

Let us read the last pages of Terra Nostra. Philip II lies in his coffin in the Escorial. As often happens in poetry marked by the baroque tradition (a tradition which is as strong in my country as in Carlos’s — another parallel between Central Europe and Latin America!), the corpse is aware of being dead. Philip of Terra Nostra lives his death. One day, he rises and leaves his coffin. He encounters a tour guide who panics and runs away. But Philip is also afraid of the guide and flees to the mountains. There he finds some peasants around a small fire. We are in the distant future. An old mountain man strokes his head and Philip is suddenly full of “a sense of comfort and gratitude.”

The encounter between Philip and the guide and the villagers is not only “beautiful like the encounter between an umbrella and a sewing machine.” It makes us hear the uninterrupted dialogue between our present and humanity’s immemorial past — that dialogue which only the novel of our late epoch (of the West’s late epoch) knows how to hear and say.

Translated by David Rieff