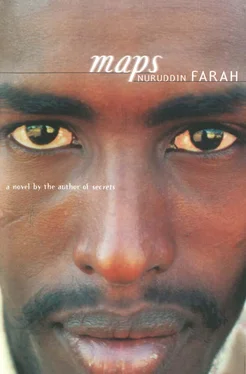

There was a brief silence which appeared endless to Askar, for it was during this period that he was to cross from the darkened area of a dreamscape to that of light. Uninitiated, it took him longer and the man repeated the greetings formula a couple of times until Askar was ready to hear and understand. The man continued: “We met but briefly, you and I, my son. My vision had just begun to grow mistier and the fog had descended on my soul, and thus I could not see nor comprehend. Greetings.”

Askar stared at him in silence.

The man went on, “And I have a message. Would you like to receive it? And will you promise to deliver it to its rightful recipient, my son?”

Askar nodded his head, but didn’t ask who the rightful recipient of the message was.

“The Prophet has said, may God bless his soul, that men are asleep. It is only at their death that they are awoken. Can you repeat that to me, word for word, my son?”

Askar nodded his head.

“Please repeat it to me, word for word.”

Askar repeated it.

“And there is another message.”

Askar indicated that he was waiting to receive it, even if it were on behalf of someone else.

“Please listen very carefully.”

Askar waited.

The man said, “An eagle builds a nest with its own claws.” There followed a slight pause. And the man waited. Askar repeated, “An eagle builds a nest with its own claws.” Then the man in the coarse garments of wool took Askar by the hand and the horse, without being called, joined them, but kept a distance, awaiting instructions. The man walked to where the horse was and he whispered something into its ear. And the horse nodded. The horse then indicated to Askar that it was ready to be ridden. Askar, as he mounted the horse, wondered to himself if it would grow wings as bright as dawn and fly in the direction of the morning sun. Whereupon, as they bid each other farewell, the man said to Askar, “May you be awoken in peace.”

And Askar awoke.

II

II

Awake and washed, handsome, shaven and seventeen years old, he now stood behind a window in a house in Mogadiscio — Uncle Hilaal’s house. To his right, a writing desk on which lay, not as yet filled out, a form from the Somali National University Admissions Committee, a form he hadn’t had the peace of mind to look at, because he didn’t know whether he would, after all, choose to go to university although he had passed his school certificate examination with distinction and-was within his rights to say which course or faculty he wanted. There were, besides the unfilled-out form, two other notes — one from Uncle Hilaal, in whose charge he lived, telling him that Misra had been seen in town and that she had been looking for the whereabouts of Askar and was likely to turn up any day at this doorstep; the other from the Western Liberation Front Headquarters, in Mogadiscio, requesting that he appear before the recruitment board for an interview. He stood behind the window, contemplative and very still — resembling a man who has come to a new, alien land. Presently, he left the window and picked up the forms and the notes in turn. He realized that he couldn’t depersonalize his worries as he had believed he might. It occurred to him, as an afterthought, that on reading the note from Uncle Hilaal last night when he got back (he had spent a most pleasant evening out in the company of Riyo, his girlfriend), his soul, out of despair, had shrunk in size while his body became massive and overblown. He wondered why

Misra was here, in Mogadiscio!

Askar was now big, tall, clean as grown-ups generally are, and healthy What would she make of him? he asked himself. He remembered how she used to lavish limitless love on him when sick; how she took care of him with the attentiveness of a child mending a broken toy. She would wash him, she would oil his body twice daily and her fingers would run over his smooth skin, stopping, probing, asking questions when they encountered a small scratch, a badly attended to sore or a black spot. Boils were altogether something else. They never worried her. “Boys have them when and as they grow up,” she said, repeating the old wives’ notion about boils. “They are a result of undischarged sperm.”

But how would she react to him and to his being a grown man, maybe taller than she, who knows; maybe stronger and more muscular than she? Would absurd ideas cross her mind: that she would like to give him a bath? Or would she offer to give him a wash or help him soap his back, or — why not? — sponge those parts of his body his hands can’t reach, would she? Whose look would be earth-bound, his or hers? Would he be able, in other words, to outstare her?

Standing between them, now that he had turned seventeen and she forty-something, were ten years, each year as prominent as a referee stopping a fight — ten years in which he shed his childish skin and grew that of an adult, under the supervision of Uncle Hilaal. He was virtually a different person. Perhaps he wasn’t even a person when she last saw him. He was only a seven-year-old boy and her ward and, sometimes he thought to himself, her toy too. Anyway, the ten years which separated them were crucial in a number of ways.

The world Uncle Hilaal and Salaado had introduced him to, his living in Mogadiscio with them, his schooling there and the world which these had opened up for him, was a universe apart from the one the war in the Ogaden imposed on Misra’s thinking. But how did she fare in war? Why did she become a traitor? For there was a certain consistency in one story — that she had sold her soul in order to save her body — but was this true? Was it true that she had betrayed a trust and set a trap in which a hundred Kallafo warriors lost their lives? Or did she surrender her body in order to save her soul? He then remembered that living with Misra wasn’t always full of exhilaration and happiness, that there were moments of sadness, that it wasn’t always fun. It had its pains, its agonies, its ups and downs, especially when the cavity of her womb overflowed with a tautology flow of blood once every month. When this occurred, she was fierce to look at, she was ugly, her hair uncombed, her spirit low, and she was short-tempered, beating him often, losing her temper with him. She was depressive, suicidal, no, homicidal.

That was how Karin entered his life.

III

III

Once a month, for five, six, and at times even seven days, Misra looked pale, appeared to be of poor health and depressive, and was of bad temper. And she beat him as regularly as the flow of her cycle. He used to think of her as a Chinese doll which you wound — if you waited long enough, its forehead would fall lifelessly on its chin, when unwound. A makeshift “mother” substituted her. Not one of Uncle Qorrax’s wives, no. The woman’s name was Karin and she was a neighbour, with grownup children who had gone their different ways, and a husband who lay on the floor, on his back, almost all the time, perhaps ailing, perhaps not, Askar couldn’t tell. Karin carried or took Askar wherever she went, as though he were running the same errands as herself. For a long time, he called this woman “Auntie” and never bothered to find out what her name was, wondering if she had any. For all the children in the area, including Uncle Qorrax’s, referred to her as “Auntie”, too. One of Uncle Qorrax’s sons said she was the wife of “the sleeping husband”.

Karin didn’t tell him what the matter with Misra was for a very long time. And when she did, she simply said, “Oh, Misra is bleeding”. This made no sense to Askar. He had not seen any blood (he had once had a nosebleed himself and of course knew what blood looked like) and therefore said he didn’t understand. He reasoned that this must be an adult’s way of hiding something, or Karin’s liking for speaking in parables. He couldn’t forget that it was she he had asked what was wrong with her husband and she replied that he had a backache. On making inquiries still further, this time from Uncle Hilaal, he was given the scientific name of the ailment. Now he asked, “Do you ‘bleed’ too?”

Читать дальше

II

II