There are two Algerian documents. The first one, dated 17 June 1957 and signed by Colonel Boumédienne, Chief of Staff of the Armée des frontières , reads:

This is to attest that Si Mourad has been appointed to the training corps of the EMG as an advisor on logistics and weaponry.

CC: BE, SBLA, head of the CFEMG, heads of the technical and operational units of Wilayah 8 (communications, transport, engineering. .).

The second, dated 8 January 1963, is signed by the General Secretary of the Officer Training Academy in Cherchell:

1) This is to confirm the appointment of the aforementioned Mourad Hans, a temporary civil instructor.

2) The chief of service of personnel shall be responsible for implementing this decision.

CC: personnel department of the Ministry of Defense.

For information only: Office of Military Security, district of Algiers.

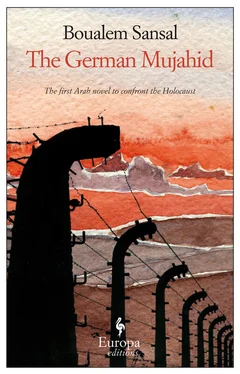

There is a battered little booklet: papa’s military record. The writing on the front is in this really impressive German gothic type. The first page lists his personal details: Hans Schiller, born 5 June 1918 in Uelzen, son of Erich Schiller and Magda Taunbach. Address: 12B Millenstraße, Landorf, Uelzen. Education: Chemical engineering, Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität, Frankfurt am Main. His regimental number is stamped in a little box, and at the bottom of the page is the signature and the stamp of the recruiting officer: Obersturmbannführer Martin Alfons Kratz. The rest is a complicated list of the postings, transfers, ranks, promotions, citations, medals and injuries he received during his career. The pages are peppered with stamps. Papa reached the rank of Captain, he was a big shot. And he was a hero too. He was wounded a bunch of times and he was mentioned in dispatches and decorated over and over! He was posted to Germany, Austria, France, Poland and other places which would have meant nothing to me without Rachel’s notes: Frankfurt, Linz, Grossrosen, Salzburg, Dachau, Mauthausen, Rocroi, Drancy, Auschwitz, Buchenwald, Ghent, Hartheim, Lublin-Majdanek. Some of the places were extermination camps. These were top-secret places where the Nazis exterminated the Jews and other undesirables. Rachel says hundreds of people died and the article in Historia says millions. Fucking hell, I thought.

I had already read Rachel’s diary over and over and I had found out a lot of stuff, but holding papa’s medals, his military records in my own hands, seeing the names, the documents, the stamps on them with my own eyes really fucked me up. I felt sick. This meant papa was a Nazi war criminal, he would have been hanged if they’d ever caught up with him, but at the same time it didn’t mean anything. I refused to believe it, I clung to something else, something truer, fairer, he was our father, we are his sons, we bear his name. He was a good man, devoted to his village, loved and respected by everyone, he fought for the independence of his country, for the liberation of a people. He was a soldier, I thought, he was just obeying orders, orders he probably didn’t understand, orders he didn’t agree with. The leaders were the guilty ones, they knew how to manipulate people, get them to do things without understanding what they were doing, without thinking. Besides, I thought, why stir up all this shit now? Papa dead, his throat cut like a sheep at Aïd, murdered along with maman and all their neighbours by real criminals, by the most brutal bastards the earth has ever produced, criminals who are supported, cheered on, even helped by people, in Algeria and all over the world. These criminals speak at the UN, they have ads on TV, they insult whoever they like, whenever they like, like the imam in the mosque in Block 17, always jabbing his finger to heaven trying to scare people, to stop them thinking for themselves. I can understand Rachel’s pain, his whole world falling apart, I can understand why he felt guilty, tainted, why he felt that somehow, somewhere, someone had to atone. Rachel was the one to atone, though he had never hurt anyone in his life.

I know it sounds incredible, but I didn’t know anything about the war, the extermination. I’d heard bits and pieces, things the imam said about the Jews and other stuff I’d picked up here and there. I always thought it was like a legend, something that happened hundreds of years ago. But the honest truth is I didn’t think about it much, I didn’t care, me and my mates, we were young, we were broke, all we cared about were our own lives. Rachel wrote terrible things. Everything was boiling over in his mind — words and phrases I’d never heard before cropped up again and again: the final solution, gas chambers, Kremas, Sonderkommandos, concentration camps , the Shoah, the Holocaust. There was a phrase in German, I didn’t know what it meant and Rachel didn’t translate it but it sounded like a curse: Vernichtung Lebensunwerten Lebens . And another one that I recognised straight off: Befehl ist Befehl . That means “orders are orders.” When we were little, living back in the bled , papa used to say it under his breath sometimes if we argued back. Then, in French, or in Berber, he’d say, “We’re not at the circus!” It’s like what Monsieur Vincent used to say when we tried to get round him: “Just do what I told you to do, if there’s time later, we’ll talk about your ideas.”

I guess after he read all this stuff, Rachel sat up all night. Reading what he wrote about it did my head in. Rachel was clever, he could always see the big picture, he understood things. I’m not like that, I need explanations, I need time to get things straight in my head. If I’d been Rachel, the stuff in the suitcase would have meant nothing to me, all I would have thought was: my parents have been murdered and I’ll never see them again. I’d have thought: papa was a soldier back in Germany, then he came here to train the maquis , end of story. The only thing that seemed weird to me was that with all the experience he had, papa ended up in a godforsaken hole like Aïn Deb. I’d have been off to California, I’d have been a stuntman in Hollywood or a bodyguard to some rich heiress. But that was papa, he was a bit of a poet, a bit like those weirdos who get up one morning, sell their big city apartments and head off to the mountains to raise sheep that wolves will end up eating before they do. Papa went a lot farther, he went to Aïn Deb. It was the perfect place, really — even Algerians have never heard of it. Or at least they hadn’t until 25 April 1994.

I’m going to finish with something Rachel wrote, I think about it all the time: “Here I am, faced with a question as old as time: are we answerable for the crimes of our fathers, of our brothers, of our children? Our tragedy is that we form a direct line, there is no way out without breaking the chain and vanishing completely.” There’s one more thing. I’ve made a resolution: someone needs to put a stop to the imam from Block 17 before it’s too late.

RACHEL’S DIARY, TUESDAY, 22 SEPTEMBER 1994

Face pressed to the window, I stare out at the carpet of clouds. Everything is white, the clouds and the sky, motionless, flickering fit to blow a fuse. I close my eyes. My thoughts are waiting for me, dark and murky, ready to drag me under. I feel exhausted. I open my eyes and look around. The plane drones gently, it is packed with passengers glowing with health, the light is mild, the temperature milder still. The passengers bury themselves in their newspapers, whisper to each other or doze. They are Germans, for the most part. This is their regular commute. When I was checking in at Roissy, I noticed most of them didn’t have any luggage, just a roll-on Samsonite, a briefcase, a couple of magazines tucked under their arm. This is routine to them, they could do the trip blindfolded. They’re freshly scrubbed, well-groomed, long-suffering as Buddhist monks. They’re tired, but they never let it show. It’s a matter of habit and considerable self-discipline. There is something terrifying about the deathly daily commute that passes for life in Paris. Somehow on a plane it’s even more depressing. Airports are the anthills of the third millennium, high-surveillance hubs with their business hotels like glass prisons, the hidden loudspeakers spouting counter-fatwas born in the bellies of all-powerful computers. When they arrive, there are the buses, the metros, the trains, the lines of taxis waiting to shuttle them onwards until at last everyone disappears into their hermetically sealed homes. Anonymity is daunting, definitive, spanning the planet and the movements of capital. These people arrive in Paris every morning, attend their business affairs, then take a plane back the same night or the next day, and by the time they land there another flight is waiting for them. They come and go and all they need to pack is a toothbrush. I’m just like this when I travel on business — a robot, all I need is an oil change and a socket to plug in my electric razor. I arrive, do what I have to, go back to the hotel, pick up my things and head back to the airport. Now and then we let our hair down. With the Italians, the Spaniards and the Greeks, it happens all the time, it doesn’t matter whether business goes well or badly. Mediterraneans like to party, we can be crude, rude, tell each other anything — that’s how we relax. The Germans, the Austrians, the Swiss and the English are different, work is their religion and their hobby. We might take time off for a coffee break occasionally, talk about the weather. The most thrilling places to me are the former dictatorships still riddled with red tape, violence and corruption. I love the film-noir feel of these places, they still cling to the best of socialism, the conspiracy, the cloak and dagger politics, but have adopted the choicest parts of capitalism, its killer instinct. All these hopeless people who shuffle along, and the others who are constantly chasing some insistent rumour that will not let them rest until they’re dead. The murkiness, the mystery, the frenzy, the misery. And the joy when — by the purest fluke — you stumble on some nameless civil servant, some nondescript hanger-on who, with a magician’s flourish, makes one phone call and breaks the impasse in a public finance contract someone has just sworn would never be resolved. That’s when parties start, the endless round of formal ceremonies, not to commemorate a successful conclusion to an honest negotiation or the miraculous release of a bank transfer — that would be tasteless — no, to celebrate the friendship between our two great countries, the entente cordial between their great leaders. By the time you get home, you have lots of stories to tell your friends, and you can exaggerate as much as you like without the fear of overdoing it: a spy here, a hit man there, an assassination attempt in a hotel lobby, the minister who strangles his secretary in the middle of negotiations for leaving out a zero in a memo, the minister who pisses on lobbyists who are not from the same tribe as he is, the leader who gasses a rebel village then flies around in his Sunday best apologizing and proclaiming a new world order. You hear a lot more than you ever see. In these countries of constant mourning, rumor and gossip are the lifeblood of every day, every minute. I’ve never quite understood how our bosses manage to make any money out of these power-mad lunatics desperate to keep every penny to themselves, but then again, we sell pumping systems, something people can’t live without, and even if we’re motivated purely by greed, it will never be as big as their appetite. We’ve got pumps in all colours, to suit all tastes, horizontal and vertical, manual and remote, tiny pumps the size of a marble and vast installations you’d need to build a hangar to hide. We’re the market leader, we have something to tempt even the most difficult customers.

Читать дальше