It is astonishing how life endures. Many villagers had survived the carnage by disappearing into the thick night, hiding as best they could, others played dead, while others still did not know by what miracle they survived. They recognised me as soon as they saw me. “It’s Rachid,” they cried, “Cheïkh Hassan’s son!” They rushed over and crowded around me, the children going through my pockets as though I was some wealthy uncle coming home. I couldn’t shake off my stilted politeness, I stood stiffly, head high, glancing around me, stammering words that sounded strange and grating to my ear. I listened as I idiotically babbled “ Salam, salam! ” I was welcomed, fussed over, thanked, congratulated. Normal roles had been reversed, the poor were comforting the privileged. For my part, I was shell shocked. I barely recognized my childhood friends, they looked so old, so pitiful it was unbearable, they looked almost like bedridden invalids you take outside in the morning so they can sit in the sun, and bring in again when night falls. The sight of them, with stumps for teeth, grey hair, deep wrinkles, hunched backs, made me feel guilty. Their hands looked thick and arthritic, the story of their short lives could be read in the ridges and their calluses. Those who had been old when I had first known them looked exactly as they always had, though maybe more alive than their children. When death comes knocking, life suddenly revives. We talked and talked some more, we talked for three whole days. The little Arabic I learned on the estate in Paris was useless. I babbled away in a mixture of French, English, German and what crumbs of Arabic and Berber I remembered, and we quickly bonded. We understood each other perfectly. To tell the truth, there wasn’t much to say: a smile, a few gestures, a few bows said all that needed to be said. Conversation is all in the mind, you carry on a conversation with yourself, answer your own questions, while a look, a gesture, is enough to sum it up to others. When it came down to it, all I was trying to say was, “I’m very well, thank you, Allahu Akbar .” Then I moved on to the next person, said the same things, drank some more coffee. I went from house to house, rediscovering the places, the smells, the mystery of a childhood suddenly rekindled. I wanted to run, to nose about, to steal, to plot, to invent great new secrets I would never tell to a living soul. We talked about that terrible night. They had all lost someone close to them — a relative, a friend, a neighbour. It had happened much as I had imagined it. Crime is not difficult to understand, it is something we know intimately, something we can easily imagine, something we see, we hear about, we read about all the time. Crime is our totem pole, planted in the earth, visible from the moon. It is the history of the world. And Algeria had written a special chapter for Aïn Deb and those who lived there.

Everyone in the village came to visit me in our family home which was now filled with emptiness, with memories of which I knew only the smallest part. But childhood memories are extraordinarily powerful. The people of Aïn Deb fed me, went without so that I could eat, worried about me, watched over me in the heavy afternoon hours as I slept, and when night began to weigh on me, the last of them would quietly creep away carrying their sleeping children in their arms. I was pleased to find that my father had been respected here and my mother thought of as blessed. I felt flattered. They say that the reputation the dead leave behind is ruthlessly judged by those who survive them. My parents had had their quietus.

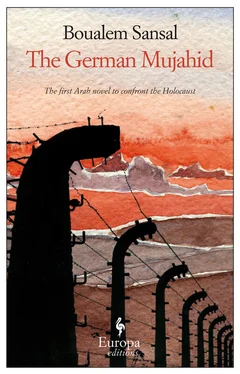

The victims of the massacre had been buried in a section of the cemetery marked out with whitewashed stones, elevating them to the status of martyrs for God and the Republic. A marble slab set into concrete inscribed in Arabic says as much. I counted thirty-eight graves in neat rows. To a small village, this brutal loss had been devastating. Carved into the gravestones were the names of those who had died, a verse from the Qur’an and a little flag. The regional administration had planned and funded the memorial. The inauguration ceremony attracted officials from civil, military and religious authorities and a national TV crew. They arrived in a cortege, and left trailing a glorious cloud of dust, leaving behind the village which had served them as a film set and the villagers whose walk-on parts they had momentarily upstaged. I had been worried that my father, a Christian, would be buried elsewhere, something that would have upset me, but his grave was next to my mother’s in the martyrs’ section. On their headstones were the names Aïcha Majdali and Hassan Hans known as “Si Mourad.” This strange anomaly again. It was only now that I found out that papa had converted to Islam in 1963. After Independence, he decided to settle here in Aïn Deb. At first, the villagers found it strange, even inappropriate for a German, a Christian, to decide to live among them, but since papa had fought in the War of Independence and earned the title Mujahid, and since he was an Algerian national, they felt honoured. Three months later, charmed by the young and beautiful Aïcha, the daughter of the village cheïkh, papa converted to Islam in order to marry her and took the name Hassan. He was forty-five, she was eighteen. When the old cheïkh died, the villagers conferred the title on papa. It was a formality, really, since everyone already referred to him as Cheïkh Hassan. They came to consult him, to listen to him, he had a solution for everything, they were amazed by the changes he made to the village. Strangers passing through — admittedly, as infrequent as the rain — used to go away astonished, half-believing Aïn Deb was not in the same country. Papa’s wisdom, his experience, his flair for organisation and natural authority had argued in his favour without any need to plead his case. This was something else I didn’t know. Though, as I child, I heard people call him Si Hassan, I thought it was just a nickname. They called him Si Mourad too, the name he used in the maquis during the War of Independence, later they called him Cheïkh Hassan, but I just assumed it was a mark of respect for his age.

Having made my pilgrimage, and having been so warmly welcomed, I soon felt at peace again. My breathing slowed, each breath now filled with courage, each sigh with noble self-denial. Everyone I met offered me words of comfort that harked back to that ageless, tragic condition of man, the essential humanity without which he would be nothing more than an automaton wandering in the desert, rusting without knowing it: “To God we belong and to Him we return. . We are but dust in the wind. . No one can knows what lies beyond death. . Believe in God, he is the resurrection and the life. . Allah never forsakes his own. .” Here in this sacred atmosphere, in this place where death had passed like a blast of the apocalypse, these phrases resonated oddly with me. Being so far from everything in this devastating but exhilirating emptiness, borne up by this sense of time passing unhurriedly, by these infallible memories, by words which have crossed the centuries, questioning and humanizing the unknowable, fosters a sense of infinite and unshakeable patience, of transcendence. You do not see yourself moving towards this blessed state, but suddenly you are someone else, someone who observes the world serenely, asks no questions, feels no fear. It is wonderful and terrifying at the same time. You spurn life, rise above it, look on it as inconsequential, ephemeral, illusory, even as life — indefatigable, magnificent, eternal — crushes us like grains of sand and sweeps us under the carpet.

I was worried when I read this part of Rachel’s diary. I’ve cut out a lot of stuff and kept the best bits, the rest is the sort of bullshit you hear in the mosque. I’ve had my fill of sermons like that. Back in the day, I was a regular in the basement of Block 17, where the jihadists had a mosque for anyone who wanted to come. You’re hooked before you know it — it only takes three sessions, and there are five prayers a day and you don’t get any days off. This is the sort of stuff they talk about all the time there: “real” life, paradise, djina , they call it, the houris , the Companions of the Prophet, the saints of the Golden Age, God’s perfect system, Brotherhood, then everyone smiles that merciful smile and hugs like veterans of some holy war, thinking hard about Jerusalem— El Qods , they call it. At first, it was cool — me and my mates went because we enjoyed going. Then a bunch of other people showed up with this new imam who was a leader in the AIG — the Armed Islamic Group — and the whole laid-back vibe turned into this terrifying madness and we were all caught in the headlights. Suddenly the only thing anybody talked about was jihad and the martyrs of Islam, about kaffirs and hell and death, about bombs and rivers of blood, about the end of the world, and noble sacrifice, about exterminating the other. Even outside, after we’d been to the mosque, we talked about it all the time. Then, the next time we heard the muezzin, we’d head back down to the basement wearing a black band round our foreheads, bloodthirsty and ready for action. When I got expelled from school, the new imam was delighted. According to him, school was a crime perpetrated by Christian dogs, the mosque was the future. I’d never really had much time for school, but I’d never thought about it like that. The imam said, “I will teach you what Allah expects of you, I will open the gates of paradise for you.” I made my excuses, said I had some training course to do and got the hell out of there. Momo kept going, he was really into all that shit, but when he got to Taliban level, he found out the meaning of pain. When you get to be a Taliban — a student of Islam — leaving is considered desertion. The jihadists caught up with him and beat him to a bloody pulp. He would have died if we hadn’t got him to hospital. We told the doctors he’d been run over by a truck. Momo spent two weeks in there being spoiled by the nurses. The jihadists were planning to finish him off in hospital but they didn’t get round to it and then they ran out of time. It was round about then that Raymond, who’d been going round calling himself Ibn Abou Mossab, asked his father to help get him out of there. Raymond was in deep shit by then, he already had his plane ticket to Afghanistan and the manual for the training camps in Kabul. He was only seventeen, but on his fake papers they’d added ten years and a big beard. After he got his son out, Monsieur Vincent set up a neighbourhood watch committee and that’s when all hell broke loose. They managed to get the mosque in Block 17 closed down for health and safety reasons, but the jihadists just set up again straight away in the back of a Moroccan grocery shop. Com’Dad is in there all the time, he’s big friends with the owner.

Читать дальше