Idly he picks up a page from the table.

“I have so many things to do today:

I must murder the rest of my memory,

I must turn my soul to stone,

I must learn to live again.”

He recites the lines without once consulting the page before letting it fall back onto the stack. “This weightiness, it has to be earned, and the price is high. Not everyone, you know, is willing to pay the price of immortality.”

I should be in bed, not lingering in the kitchen in my nightgown, memorizing dangerous poetry and talking to strangers, but I speak without thinking, before I can excuse myself and leave. “I thought this hasn’t been published. How can it be immortal if no one can read it?”

“Perceptive but wrong, my dear child. It’s like that tree falling in the forest when no one is around. Rest assured, there are powers that see and hear everything happening in this world. And in any case, aren’t you reading it right now? Manuscripts do not burn, as another immortal once said—though you are probably too young to have read him just yet. How old are you, anyway?”

The jazz music of my parents’ party is coming from somewhere very far away.

“Thirteen.” I lick my dry lips. I realize that I never did get that cup of water. Battalions of smeared glasses have been abandoned in careless disorder near the sink, and from where I sit, an arm’s length away—everything in our kitchen is only an arm’s length away—I can smell the half-honeyed, half-acrid scent of unfinished wine. “The age of Juliet,” I nearly add, but say instead, “I’ll turn fourteen this summer.”

“Oh, you have some time. Not too much time, mind you,” he says airily as he glances at the clock on the wall, and as if on cue the cuckoo creaks, bowing on its perch; it is three in the morning. “Time, you know, is the ultimate limitation placed on man, and you need to be supremely aware of your limitations if you desire to become a poet. Of all the different kinds of art, you see, poetry is the one most attuned to man’s condition, and therefore the most noble and the most demanding of them all. Just as men struggle to transcend the inherent limits of geography, history, and biology to find the meaning of life, so poets strive to transcend the inherent limits of language, meter, and structure to find beauty and truth. And just as life wouldn’t have meaning without death, so poetry wouldn’t have its sublime power outside the prison of its form.” He nods at the manuscript before me: “Which makes it even more powerful when you combine the limitations of language with the repressions of history. But the opposite is true as well. Poetry diminishes in times of plenty, loses its urgency and hunger, grows flabby. People of each age get just the poetry they deserve.”

As he continues to talk, I begin to feel dizzy with the sense of utter strangeness and, at the same time, a kind of novel, intoxicating freedom. The kitchen has ceased to be the familiar place where I eat rushed breakfasts on school mornings while my mother waters her windowsill herbs and my father fumes at the day’s headlines. In this new place, at this unearthly, in-between hour, the chilled, crisp sweetness of an April night enters through the cracked window like some barely audible promise, and souls of banished words are resurrected in guilt-ridden whispers, in paling print, in a stranger’s languid, knowing drawl, to hang in the air, dark and light and eternal, mixing with the heady smell of spring, swelling my chest with some immense, nameless longing.

The man with the handsome face of a ruined god is watching me closely.

“Do you want to be immortal?” he asks.

“What?”

“It’s a simple question and a simple matter. Do you want to be immortal?”

I want to say: I don’t know what you mean. I open my mouth.

“Yes.”

He smiles again—a real, warm smile this time, though somehow cruel in spite of its warmth. All at once I think: If I lean forward ever so slightly, his breath will brush my face. I feel my skin growing hot. I do not lean forward.

The man stands, his movements fluid with loose, predatory grace. I am shocked to see bare feet protruding from the frayed cuffs of his pants.

“Well, time for a rude awakening,” he says. “I could take a dramatic leap off the windowsill, but something tells me you are not easily impressed with clichés, so let me make a more subtle exit. Time waits for no man, memento mori , and all that.”

The clock creaks on the wall, and as I look up, I see the cuckoo taking its three bows, one left, one right, one straight, which seems impossible, since it was three o’clock some ten minutes ago, unless the hands have started going backward, and then the cuckoo calls out “Cuckoo! Cuckoo! Cuckoo!” in the hoarse voice of my earliest childhood memories, and the man with the face of a thwarted angel jauntily sidesteps the bird and disappears inside the clock, which is when I know that I am asleep, just seconds before I know that I am awake because my father is shaking me.

“And what is the meaning of this?” my father asks with severity.

My head has fallen on the Requiem typescript. I can hear Orlov roaring with laughter in the doorway.

Nineteenth-Century Porcelain, or The Meaning of Life

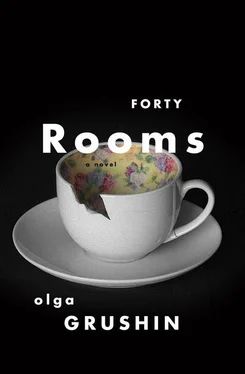

My fingers are still sooty from the bonfire, and as I pick up my cup, I watch them leave faint smudges on the trellised flowers. We use simple cups at the dacha as a rule, thick and earth-colored, which remain rattling in the cupboard after we return to the city; but this morning my mother packed her best porcelain into starched nests of napkins, to be brought to the country along with cold chicken cuts and her famed apple pie.

I notice Olga studying the cups as well.

“Pretty,” she says. “Are they old?”

I nod. “Nineteenth-century. Mama collects them.”

“It suits you, you know. Ballet dancers, gypsy ancestors, family jewels, old porcelain. You’ll be reading by candlelight next.”

I laugh. “Are you saying I’m anachronistic?”

“I was thinking romantic. But I suppose it comes to much the same thing.”

“I see what you mean. A seventeen-year-old maiden sitting on the balcony at dusk, drinking tea made with water drawn from the village well.”

“With a full moon rising,” she says.

“With a nightingale singing in the bushes,” I rejoin.

“With facilities in the yard,” she says.

“Oh, now you’ve gone and ruined it! That’s hardly romantic.”

“But true,” she says, laughing also.

“Which is my point precisely. Truth can’t be very romantic.”

“Well, in any case. Nice cups. Sorry about the fingerprints.”

For a while I sip the tea in silent contentment. I can feel the dacha’s peaceful darkness behind my back. After driving here in the morning, laden with provisions, my parents have gone back to the city, to return three days hence; this lull of solitude is my graduation present of sorts, a foretaste of adulthood, a short spell of freedom between two anxiety-ridden stretches of last-minute cramming: the high school exams ended last week, the university entrance exams will commence next month. The June evening is blue and clear, the roofs at the end of our unpaved street stand out with crisp precision against the pale breadth of fields merging with the pale depth of the sky, and the world feels marvelously light, and I feel marvelously light too, as if I might take off at any instant, sail away in the small boat of the balcony into that luminous distance, the sweet smells of grasses and clover, the exhilarating expanse of the never-ending horizon—and splash through the slight chill in the air as through the waters of some cool, delightful stream, and catch the bright yellow moon like a leaping fish in my hand… But the balcony is moored to the rickety house by tenacious tendrils of ivy, my mother’s precious porcelain cup feels dangerously fragile in my fingers, and Olga is talking again.

Читать дальше