Apollo’s Arrow

The three large windows glowed with a perfect April sunset; its colors reminded her of a tropical drink in a glossy advertisement—something cool, sweet with fruity liqueurs, crowned by a pink paper umbrella. From up here, the rows of townhouses on the street below, with their dark tile roofs and neat arrangements of potted plants on the narrow balconies, looked clean, toylike, European somehow, and she said so, more in the spirit of indiscriminately voicing her thoughts aloud than of making conversation, for with Paul she did not much think of what she said.

“Though I’ve never been to Europe. Well, technically Moscow is Europe, but it isn’t really. Yes, we are Scythians, yes, we are Asians with slanting, greedy eyes, and all that.”

He looked up from slicing the mushrooms. “What was that Scythian bit?”

“Oh, just some famous lines from Blok.” She added after a beat, “A Russian Silver Age poet.”

“Ah. Poetry. Never got into it myself. Anyway, Europe. You should really go, you know.”

“Travel’s not so easy for me,” she said. “I have issues with documents—”

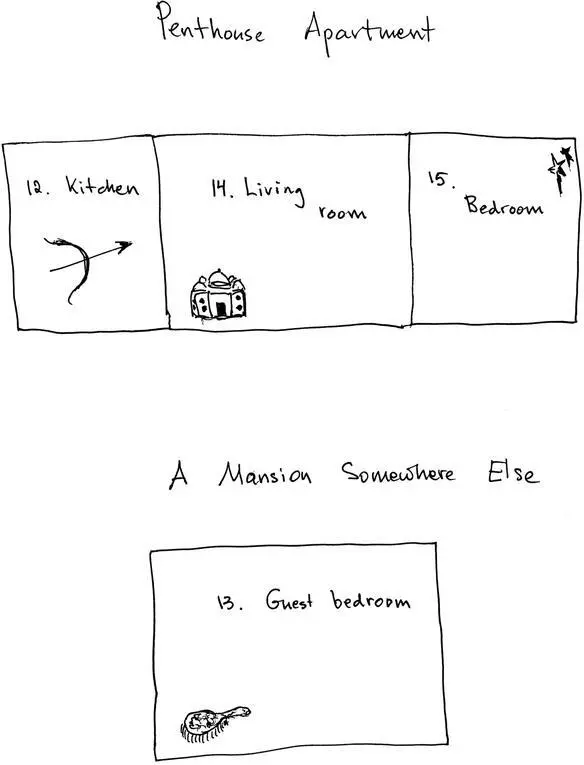

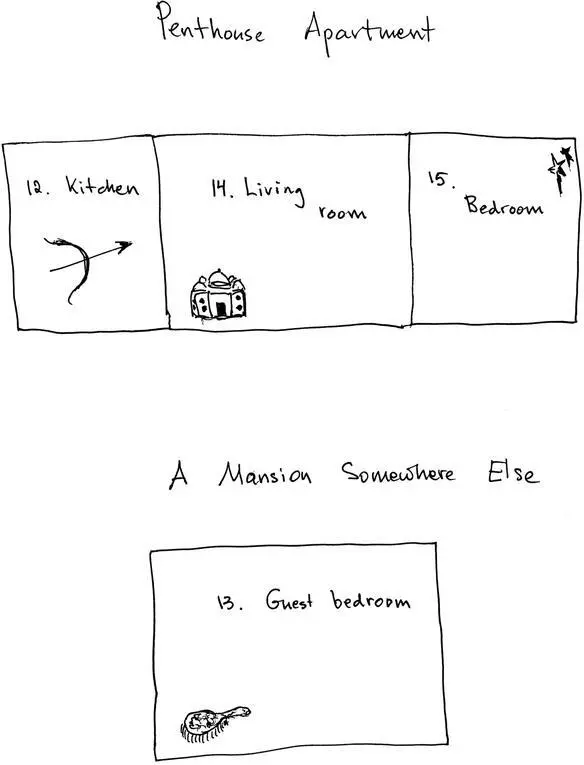

She could have added, “Nor do I have the money,” for in truth she was nearly destitute. She had long before quit her day job in a department store and her night job in a restaurant, and now survived by taking on occasional translation projects; the assignments, however, paid by the page, and she had proved inconveniently slow, agonizing as she did over the most trivial word choices with all the obsessiveness of a thwarted poet. Every night she jotted down her earnings (“Proposal for installing latrines in Central Asia, 3 pages, $48”) as well as her expenses (“March rent, $525; apples, $3.60; bus from the library, $1.10”; she always walked there to save the fare, but the piles of books she invariably checked out were too heavy to lug home on foot). At the end of each week, if the subtractions worked out, she would allow herself the single luxury of a cappuccino and pastry in a nearby café. She carried her poverty lightly—she believed that her upbringing had inoculated her against needing comforts or longing for possessions—but she sensed that any mention of her situation might embarrass Paul, who, after finishing business school, had landed a vague but clearly well-paid job at some management consulting firm and was now living in a furnished penthouse apartment in a finer part of the city.

Quickly she changed the subject.

“Are you sure I can’t lend you a hand?”

“I would never make a guest cook. Besides, I love cooking for people. Just sit back and enjoy your Chardonnay, dinner will be ready in no time.”

Swirling the wine in her glass, she watched him as he moved between the stove and the island with an agility unexpected in someone of his massive build, until at last she admitted to feeling surprised, and pleasantly so. Ever since they had run into each other on a street downtown (he had been leaving his new office; she, walking to the library), they met for coffee every few months, but this was the first time he had invited her over for dinner. She had, she realized, envisioned a grimy bachelor’s den and a plate of overcooked spaghetti topped with lukewarm sauce from a can (the extent of her own culinary endeavors). In the near-ascetic bareness of her life, had she fallen victim to the trite assumption that someone at ease with numbers—just as someone at ease with words—could never be altogether at ease in the physical world? It held true in her case, to be sure, yet here was Paul the math major in a white apron embroidered with grapes, wielding a knife with efficient grace as he chopped asparagus in his immaculate kitchen, exuding a sense of serenity amidst boiling pots and hissing pans and mysterious gleaming utensils at whose purpose she would not even attempt to venture a guess.

She found his capable presence relaxing.

“I hope it won’t be too rich for you,” he said as he stirred more cream into the sauce. “I haven’t tried this one before, it’s from a new cookbook—”

“Whatever it is, the smell is making me hungry… And just look at all these books! I don’t have any books in my kitchen. Granted, my entire kitchen is the size of a teapot—” Wineglass in hand, she rose from the table and inspected the shelves, then, pulling a book out at random, leafed through it idly.

“But these are like poetry,” she exclaimed then. “Ossobuco Gremolada with Risotto Milanese! Marseille Bouillabaisse with Aïoli! Or how about this militant Duck Flan with Maltese Blood Orange Sauce and Shallot Confit? I don’t think I know two-thirds of these words. Can anyone actually cook these?”

“Possibly. One never knows until one tries,” he said, smiling.

“And you have two entire books of desserts! I can never pass up anything sweet, it’s my one weakness… Here is something called Casanova’s Delight. Mmm, it has kiwi sauce and Grand Marnier ice cream mousse.”

He stepped closer, bumping her arm. “Oh, sorry. Let me see. This one’s a little ambitious.” As always, when he stood next to her, she was startled by his football player’s bulk. “Still, let’s brave it for our next dinner, shall we?”

“So generous of you to volunteer feeding the masses.”

He resumed his place at the stove, his face reddened with the heat of cooking.

“So,” he said after a short pause, “heard from any of the old crowd lately?”

“Just Lisa.” She opened another book. “She married Sam, you know, as we all expected. They’ve just had a boy. What in the world is cardamom?… And Maria and Constantine split up, but I haven’t spoken to either of them since.”

“I keep in touch with them. Maria is in New York, trying to break into acting. Constantine went back to Greece and inherited his shipping empire. And Stacy is renting her own childhood room from her parents. They are crazy as bats, she says. And, of course, the horrible thing with John… Not that I liked him much, always thought he was a pretentious ass, but one shouldn’t speak ill of—”

“Who?” she asked, turning a page. She was enchanted by the precisely quantified lists of exotic ingredients, the casual mentions of distant places, the pure linguistic pleasure of melodiously named concoctions—a vocabulary entirely new to her. Since Adam’s departure (fourteen months, eight days, and two hours ago now), she had barely stirred from the monastic confinement of her dim basement cell, and she felt her very soul squinting, blinded by the brightness of life out in the open, so sophisticated and varied, so full of adult things she appeared to know nothing about. It occurred to her that she was not giving the senses their proper due. It might be interesting to attempt a poem for each sense, like the verbal equivalent of one of those allegorical seventeenth-century paintings with Lady Taste licking a sugared plum, Lord Sight studying stars through a telescope, Lady Smell lifting a rose to her nose, and Lord Hearing serenading the courtly gathering on a mandolin, while Lord and Lady Touch pawed each other in the discreetly darkened bushes in the background. The Hearing poem would be the easiest, no doubt, sprinkled liberally with alliteration and onomatopoeia, but the others would present a challenge, for the trick would be to convey in words alone the unique nature of—

“John. Hamlet. Didn’t you date him at one point?”

“Oh,” she said, closing the volume. “Yes. Briefly. Did something happen to him?”

Читать дальше