He had the house to himself for the weekend.

A bed, two even.

And food, TV, anything he wanted.

Furo locked his mind on the TV, which showed a Nollywood movie, and in the scene a weeping woman sat in jail with a bloodied, shirtless man. The woman’s crying sounded strained, the movie jail was a real garage — motor oil spots on the floor, filigreed grille for a door — and the make-up blood looked like make-up blood. Furo changed the channel, and kept on changing, his thumb tapping the keys, the remote wedged against his belly, his knees spread apart and his shoulders slouched, his eyes blinking as the TV flickered and switched voices in mid-sentence: here’s some peri peri, a much stronger bite, dominate the headlines, nothing but Allah’s favour, love potting around, Jerry! Jerry! Jerry! , cocoa boom era, hungry man size, avoid Gaddafi’s fate, last scrap of hope, her majesty the queen, we make our own beef, terrible for tennis, stadium crowd chanting , still capable in spurts, battle to reach each level, xylophone tinkling , accused of phone hacking, can withstand his might, right to be proved wrong, hit you like ooh baby , off the starboard bow, what happened elsewhere, love can save the universe, loud audience laughter —

His phone rang: he could hear its plaintive jangling below the TV’s barrage. He jumped up from the settee and ran into the bedroom and grabbed the phone from the bed. It was Syreeta calling. ‘Phone was in the bedroom,’ was the first thing he said. And then, ‘I was watching TV.’

‘Enjoy,’ Syreeta said. ‘I just remembered I hadn’t asked you how it went. Your passport.’

‘Oh yes, it went very well. I’m supposed to collect it on Monday.’

‘We should celebrate. Do you plan to go out tonight?’

‘No.’

‘What of tomorrow?’

‘No plans for tomorrow.’

A teasing note entered her voice. ‘Don’t you do clubs? Come on, it’s the weekend!’

‘No clubbing for me,’ Furo said with a forced laugh. ‘I can’t afford it.’

‘OK then,’ Syreeta said. Her voice had reached a decision. ‘I’ll return on Sunday, in the evening. I’ll take you out, my treat. We must wash your passport.’

‘I’d like that,’ Furo said, to which Syreeta responded with a quick ‘Cheers,’ and then, as he began to express his thanks, the line went dead. Lowering the phone from his ear, he stared at it without seeing, thinking about Syreeta and her puzzling kindnesses. He knew she felt sorry for him, and he suspected she even liked him in her own hard-boiled way, but now it also seemed she trusted him, at least enough to leave her bedroom unlocked. But all of that didn’t explain why a Lagos big girl was so free with her favours, especially as she knew he had no money. He had nothing she could want, nothing at all. After all, she had seen everything, even his buttocks.

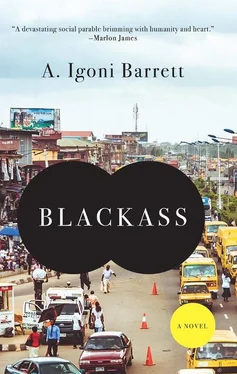

That morning, when she and he discovered his buttocks together, was branded on to the underside of his consciousness. He had awoken several times in a fright on Wednesday night, her laughter ringing in his mind. But the bigger terror was that the blackness on his buttocks would spread into sight, would creep outwards to engulf everything, to show him up as an impostor. That it hadn’t yet happened didn’t mean it wouldn’t still. That he didn’t have a hand in what he was didn’t mean he wasn’t culpable. No one asks to be born, to be black or white or any colour in between, and yet the identity a person is born into becomes the hardest to explain to the world. Furo’s dilemma was this: he was born black, and had lived in that skin for thirty-odd years, only to be born again on Monday morning as white, and while he was still toddling the curves of his new existence, he realised he had been mistaken in assuming his new identity had overthrown the old. His idea of what he was, of who the world saw him as, was shaken by the blemish on his backside. He knew that so long as the vestiges of his old self remained with him, his new self would never be safe from ridicule and incomprehension. Syreeta, clearly, had shown him that.

Thinking these troubling thoughts, Furo spent the rest of Friday with his eyes stuck to the TV screen until he tumbled off the cliff edge of his mental fatigue. He awoke what felt like mere minutes later to the human noises of Saturday morning, and after he freshened up with a quick bath and a light breakfast, after the power went and the wild clatter of generators swelled in all corners of his mind and the housing estate, after he stared at the dead TV for so long that his eyes stung from the rub of the thick-as-mud air, and then, after he fiddled with his phone until he figured out how to turn off the Caller ID, he called his old phone. It rang on the first try, and before he could recover from the shock of the expected, that voice he recognised even better than his own jolted him awake to the horror of his mistake, a mistake he only salvaged by biting down on his tongue to control the urge to reply to his mother’s hopeful hello. He cut the call, switched off the phone, removed the battery, and then bowed his head to the pounding of the generators, the machine rumble of the world.

Later, when he’d calmed himself enough to breathe easy, he made every effort to close back the portal from which the past was leaking into his head.

Saturday passed slowly, but it passed.

He rose with the sun on Sunday and washed his clothes, then wrapped his towel like a sarong and stepped out of the apartment for the first time since Friday. The yard was empty, as were the estate streets, because sunny Sundays were bumper days for churches. After hanging his washing on the clothesline, he went back inside and swept the floor, dusted the furniture, beat the hollows out of the settee, and washed his piled-up dishes. The sun’s face was sunk in a mass of thunderclouds by the time he was done with housework. He gathered in the sun-scented laundry, ironed his shirt and trousers, and took a bath. By four o’clock he was ready for Syreeta’s return.

The rainstorm struck at five. From afar the rain approached like a crashing airliner. At this sound, a rising whine that left the curtains curiously still, Furo hurried into his bedroom and stared from the window above the bed, which gave the clearest view of the sky. He smelled the raindrops before he saw them. A lash of thunder roused the wind, which rose from the dust and began to swing wildly at treetops and roof edges and flocks of plastic bags ballooning out to sea. Raindrops swirled like dancing schools of silver fish and scattered in all directions, splattering the earth and the shaded walls of houses. Furo sprinted around the apartment shutting windows.

Syreeta arrived in the rain. As was usual during a storm, the power had gone, and Furo was stretched out on the settee, not asleep but drifting there, lulled by the drumming on the roof and the wind whistling outside the windows. He started upright when he heard the key in the lock. The door banged open, Syreeta rushed in, turned around in the doorway to close her umbrella and shake water from it, then kicked the door closed and bent down to rest the umbrella against it. She was barefooted. The bottoms of her jeans were rolled up to her knees. Her braids were gathered in a shower cap, and when she came closer Furo saw she was shivering. Her face was angled with annoyance.

‘You came in the rain!’ Furo exclaimed in welcome, but Syreeta made no response as she strode into her bedroom and slammed the door.

Furo stood up from the settee and skulked off into his bedroom. He took off his clothes and hung them in the wardrobe to preserve their freshness, and then slipped into bed and pulled the blanket over his head. Syreeta’s mood had dampened his, and the excitement he’d nursed all day at the thought of their going out was now a fluff of fear in his belly. He felt like a chided child, driftwood in angry currents, at the mercy of whims as changeable as Mother Nature’s.

Читать дальше