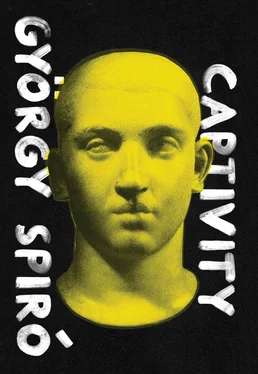

György Spiró - Captivity

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «György Spiró - Captivity» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2015, Издательство: Restless Books, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Captivity

- Автор:

- Издательство:Restless Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2015

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

Captivity: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Captivity»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A literary sensation in Hungary, György Spiró’s Captivity is both a highly sophisticated historical novel and a gripping page-turner. Set in the tumultuous first century A.D., between the year of Christ’s death and the outbreak of the Jewish War, Captivity recounts the adventures of the feeble-bodied, bookish Uri, a young Roman Jew.

Frustrated with his hapless son, Uri’s father sends the young man to the Holy Land to regain the family’s prestige. In Jerusalem, Uri is imprisoned by Herod and meets two thieves and (perhaps) Jesus before their crucifixion. Later, in cosmopolitan Alexandria, he undergoes a scholarly and sexual awakening — but must also escape a pogrom. Returning to Rome at last, he finds an entirely unexpected inheritance.

Equal parts Homeric epic, brilliantly researched Jewish history, and picaresque adventure, Captivity is a dramatic tale of family, fate, and fortitude. In its weak-yet-valiant hero, fans will be reminded of Robert Graves’ classics of Ancient Rome, I, Claudius and Claudius the God.

"With the novel Captivity, Spiró proved that he is well-versed in both historical and human knowledge. It appears that in our times, it is playfulness that is expected of literary works, rather than the portrayal of realistic questions and conflicts. As if the two, playfulness and seriousness were inconsistent with each other! On the contrary (at least for me) playfulness begins with seriousness. Literature is a serious game. So is Spiró’s novel.?"

— Imre Kertész, Nobel Prize — winning author of Fatelessness

"Like the authors of so many great novels, György Spiró sends his hero, Uri, out into the wide world. Uri is a Roman Jew born into a poor family, and the wide world is an overripe civilization — the Roman Empire. Captivity can be read as an adventure novel, a Bildungsroman, a richly detailed portrait of an era, and a historico-philosophical parable. The long series of adventures — in which it is only a tiny episode that Uri is imprisoned together with Jesus and the two thieves — at once suggest the vanity of human endeavors and a passion for life. A masterpiece."

— László Márton

“[Captivity is] an important work by yet another representative of Hungarian letters who has all the chances to become a household name among the readers of literature in translation, just like Nadas, Esterhazy and Krasznahorkai.… Meticulously researched.… The novel has been a tremendous success in Hungary, having gone through more than a dozen editions. The critics lauded its page-turning quality along with the wealth of ideas and the ambitious recreation of historical detail.”

— The Untranslated

“A novel of education and a novel of adventure that brings to life ancient Rome, Alexandria and Jerusalem with a vividness of detail that is stunning. Spiró’s prose is crisp and colloquial, the kind of prose that aims for precision rather than literary thrills. A serious and sophisticated novel that is also engrossing and highly readable is a rare thing. Captivity is such a novel.”

— Ivan Sanders, Columbia University

“György Spiró aspired at nothing less than (…) present a theory in novelistic form about the interweavedness of religion and politics, lay bare the inner workings of power and give an insight into the art of survival….This book is an incredible page turner, it reads easily and avidly like the greatest bestsellers while also going as deep as the greatest thinkers of European philosophy.”

— Aegon Literary Award 2006 jury recommendation

“What this sensational novel outlines is the demonic nature of History. Ethically as well as historically, this an especially grand-scale parable. Captivity gets its feet under any literary table you care to mention."

— István Margócsy, Élet és Irodalom

“This book is a major landmark for the year.”

— Pál Závada, Népszabadság

“It would not be surprising if literary historians were soon calling him the re-assessor and regenerator of the post-modern novel.”

— Gergely Mézes, Magyar Hírlap

“Impossibly engrossing from the very first page….Building on a huge volume of reference material, the novel rings true from both a historical and a literary point of view.”

— Magda Ferch, Magyar Nemzet