“I’m checking it,” said Firmino.

“Do you wish to visit the great northlands of Europe?” continued Don Fernando. “Oslo, for example, the city of the midnight sun and the Nobel Peace Prize: page nineteen, leaving Zurich at 12:21 from platform 7, the ferryboat timetable is provided in a footnote. Or, take your pick, it might be Magna Grecia, the Greek theater at Syracuse, the ancient culture of the Mediterranean, to get to Syracuse you only have to turn to page twenty-one, you leave Zurich at exactly 11 o’clock, and there you will find all the possible connections on the Italian railways.”

“Have you made all these journeys?” asked Firmino.

Don Fernando smiled. He selected a cigar but did not light it.

“Naturally not,” he replied, “I have simply confined myself to imagining them. After which I return to Oporto.”

Firmino passed him the volume. Don Fernando took it, gave it a swift glance without opening it and handed it back.

“I know it by heart,” he said, “I make you a present of it.”

“But you may be attached to it,” said Firmino, not knowing what else to say.

“Oh,” said Don Fernando, “none of those trains run any more, that precise Swiss timing has been swallowed up by time itself. I give it to you as a souvenir of these days we’ve spent together, and a personal souvenir as well, if it is not presumptuous on my part to think that you might like to have something to remember me by.”

“I shall keep it as a souvenir,” replied Firmino. “And now please excuse me, Don Fernando, I have to get something, I’ll be back in ten minutes.”

“Leave the door on the latch,” said the lawyer, “don’t make me get up again to press the button.”

FIRMINO RETURNED WITH A package under his arm. He undid it carefully and placed a bottle on the table.

“Before leaving I would like to drink a toast with you,” he explained, “unfortunately the bottle isn’t chilled.”

“Champagne,” observed Don Fernando, “it must have cost you a fortune.”

“I chalked it up to my newspaper,” admitted Firmino.

“I suspend judgment,” said Don Fernando.

“With all the special editions they’ve printed thanks to our articles I think that the paper can treat us to a bottle of champagne.”

“ Your articles,” specified Don Fernando as he fetched two glasses, “they were your articles.”

“Well, anyway,” murmured Firmino.

They raised their glasses.

“I propose we drink to the success of the trial,” said Firmino.

Don Fernando took a sip and said nothing for the moment.

“Don’t cherish too many hopes,” he said as he put down his glass, “I’m prepared to bet it will be a military court.”

“But that’s ridiculous,” exclaimed Firmino.

“It’s logical according to the lawbooks,” replied the lawyer phlegmatically, “the Guardia Nacional is a military body, I will do my best to challenge this logic, but I don’t have too many hopes on that score.”

“But this is a brutal murder,” said Firmino, “a question of torture, of drug peddling, of corruption, it’s got nothing to do with war.”

“Of course, of course,” murmured the lawyer, “and tell me, what’s your fiancée called?”

“Catarina.”

“A beautiful name,” said the lawyer, “and what does she do in life?”

“She’s just taken an exam for a post at the city library,” said Firmino, “she’s a graduate of library sciences, and a qualified archivist, but she’s still waiting for the results.”

“Working with books is a wonderful way of life,” murmured the lawyer.

Firmino refilled the glasses. They sipped away in silence.

Finally Firmino picked up the bound volume and got to his feet.

“I think it’s time I was going,” he said.

They shook hands briefly.

“Give my best to Dona Rosa,” Don Fernando called after him.

Firmino went out into Rua das Flores. A fresh breeze had sprung up, it almost had a nip in it. The air was as clear as crystal, he noted that the leaves of the plane-trees were patched here and there with yellow. It was the first sign of autumn.

OF THAT DAY FIRMINO WAS destined to remember chiefly his physical sensations, lucid enough but as foreign to him as if he hadn’t been involved at all, as if a protective film had cocooned him in a state between sleep and waking, where sensory perceptions are registered in the consciousness but the brain is powerless to organize them rationally, leaving them floating around as vague states of mind: that misty late-December morning when he arrived shivering with cold at the station in Oporto, the local trains unloading the early commuters with their faces still puffy with sleep, the taxi-ride by those sullen buildings of that damp and gloomy city. The whole place depressed him immensely. And then his arrival at the Law Courts, all that red tape at the entrance, the block-headed objections of the policeman at the door, who frisked him and wouldn’t let him in with his pocket tape-recorder, his Union of Journalists’ card which finally did the trick, his admittance to that tiny courtroom where all the seats were taken. He wondered why, for such an important trial, they had chosen such a small room, of course he knew the answer, although in that state of mingled insentience and hyper-awareness he was unable to articulate it mentally, and went no further than registering the fact.

He finally managed to find a place on the narrow dais reserved for the Press, segregated by a dark-stained, pot-bellied-columned balustrade. He had expected a crowd of reporters, photographers, flash-bulbs. But there was nothing of the sort. He recognized two or three colleagues, with whom he exchanged brief nods, but the rest were quite unknown to him, probably specialists in law cases. He realized that a lot of the newspapers would be falling back on information from press agencies.

In the front row he spotted Damasceno’s parents. The mother was swathed in a grey coat and dabbed her eyes every so often with a crumpled handkerchief. The father was wearing an unbelievable red-and-black checked jacket, American style. To the right, at the table where the lawyers sat, he spotted Don Fernando. He had dumped his lawyer’s gown on the table and was busy studying documents. He was wearing a black jacket and a white bow-tie. There were deep circles under his eyes and his lower lip drooped even more than usual. Between his fingers he was twisting an unlit cigar.

Leonel Torres was sitting practically huddled in his seat, looking scared out of his wits. Beside him sat a frail blonde who was presumably his wife. Sergeant Titânio Silva himself was seated with his two deputies. The latter were in uniform, whereas Titânio Silva, in mufti, was wearing a pin-striped suit and a silk tie. His hair was gleaming with brilliantine.

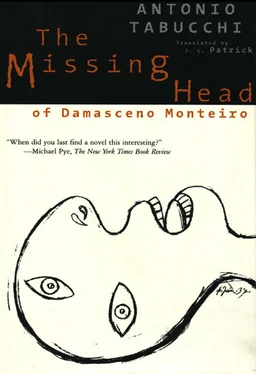

The Court entered and the proceedings began. Firmino thought of switching on his tape-recorder, but he had second thoughts because the courthouse had hopeless acoustics and the recording was sure to come out badly. Far better to take notes. He drew forth his notebook and wrote: The Missing Head of Damasceno Monteiro. After which he wrote no more, he just listened. He wrote nothing because he already knew all that was being said: the reading of Manolo the Gypsy’s testimony about finding the body, the fisherman’s statement that he had fished up the head on the line he had out for chub, and the results of the two autopsies. As to what Leonel Torres had to say, he knew that as well, because the Judge simply asked him if he confirmed what he had said during the preliminary investigations, and Torres confirmed it. And when it came to Titânio Silva he too confirmed his previous statement. His raven-black hair glistened, his hair-line mustache kept time with the motion of his thin lips. Of course, he said, his first statement to the examining magistrates was the result of a misunderstanding, because the young recruit who was with him in the car was sleepy, very sleepy, poor lad, he had come on duty at six in the morning and was only twenty years old, and at that age the body needs its sleep, but yes, in fact they had taken Monteiro to the station, and he was beside himself, at the end of his tether, he had broken down and cried like a child, he was a small-time crook, but even crooks can sometimes touch the heart, so that he himself and one of the deputies had gone down to the kitchenette on the floor below to make him a cup of coffee.

Читать дальше