“Yes, in Lisbon,” confirmed Firmino.

“We’re getting a movement going in favor of the gypsies of Portugal,” whispered the waiter, “I don’t know whether you’ve seen the racist demonstrations there have been in a number of towns around here?”

“I’ve heard about them,” said Firmino.

“People don’t want the gypsies,” said the waiter, “in one town they’ve even beaten them up, it’s an outbreak of racism. I don’t know for sure which political parties are inciting people against them though it’s not hard to imagine, and we don’t want Portugal to become a racist country, it’s always been a tolerant country, I am a member of an association called Citizens’ Rights and we are collecting signatures, would you care to sign?

“Willingly,” replied Firmino.

From his pocket the waiter produced a sheet full of signatures headed “Citizens’ Rights.”

“I ought not to have you sign in the restaurant,” he said, “because collecting signatures is forbidden in public places, we have special centers dotted all over town, but as the boss isn’t looking, right, if you just sign here, with your particulars and the number of some official document.”

Firmino wrote his name, the number of his identity card, and under the heading “profession” wrote: journalist.

“Will you give us a write-up in your paper?” asked the waiter.

“I can’t promise,” said Firmino, “at the moment I’m busy with another matter.”

“There are some ugly things happening in Oporto,” observed the waiter.

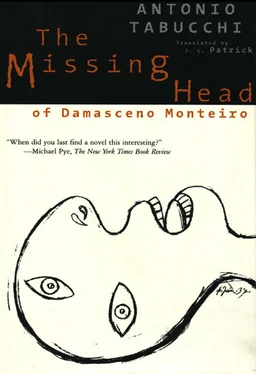

Just then a newsboy entered the café, a kid carrying a bundle of newspapers, and as he did the rounds of the tables he repeated: “The great Oporto mystery, the missing head discovered.”

Firmino bought Acontecimento . He gave it a quick glance, folded it neatly in four because he felt embarrassed. He put it in his pocket and left. He thought he had better be getting back to Dona Rosa’s.

DONA ROSA, SEATED on the sofa in the sitting-room, had a copy of Acontecimento open before her. She lowered the paper and looked up at Firmino.

“What a horrible business,” she murmured, “the poor soul. And poor you,” she added, “having to face such horrors at your age.”

“That’s life,” sighed Firmino, taking a seat beside her.

“The pretenders to the throne are a good deal better off,” observed Dona Rosa, “in Vultos there’s a feature on a splendid reception given in Madrid, everybody is so elegant.”

Just then the telephone rang and she went off to answer it. Firmino watched. Dona Rosa gave a nod, beckoning twice with her forefinger.

“Hullo,” said Firmino.

“Have you something to write with?” asked a voice.

Firmino instantly recognized the voice which had called him before.

“I’ve got something to write with,” he said.

“Don’t interrupt me,” said the voice.

“I’m not interrupting you,” Firmino assured him.

“The head is that of Damasceno Monteiro,” said the voice, “twenty-eight years old, he worked as errand-boy at the Stones of Portugal, he lived in Rua dos Canastreiros, it’s up to you to find the number, it’s in the Ribeira, opposite a fountain, you must inform the family, I can’t do it for reasons I won’t go into, goodbye.”

Firmino hung up and at once dialed the number of the paper, giving a glance at the notes on his pad. He asked for the Editor but the switchboard operator put him through to Senhor Silva.

“Hullo, Huppert here,” said Silva.

“This is Firmino,” said Firmino.

“Enjoying the tripe?” asked Silva in sarcastic tones.

“Listen Silva,” said Firmino, stressing the name, “why don’t you go fuck yourself?”

There was a silence at the other end, then Silva asked indignantly: “What did you say?”

“You heard,” replied Firmino, “now pass me the Editor.”

After a bit of electronic music on came the Editor’s voice.

“He’s called Damasceno Monteiro,” said Firmino, “twenty-eight years old, worked as errand-boy at the Stones of Portugal in Vila Nova de Gaia, I’ll go and inform his family, they live in the Ribeira, and after that I’ll go to the morgue.”

“It’s now four o’clock,” said the Editor quite casually, “if you can manage to get me a report by nine tomorrow morning we’ll come out with another special edition, today’s sold out in an hour, and just think, today’s Sunday and lots of the kiosks are closed.”

“I’ll try,” said Firmino without conviction.

“You better had,” declared the Editor, “and make sure there’s lots of colorful detail, plenty of drama and pathos, like a good slushy photo-romance.”

“That’s not my style,” replied Firmino.

“Find another style,” retorted the Editor, “a style Acontecimento needs. And another thing, mind it’s a long piece, really good and long.”

THE SCENE OF THIS SAD, MYSTERIOUSand, may we add, bloodcurdling story is the smiling and industrious city of Oporto. Strange but true: Oporto, our very Portuguese Oporto, that gentle city cradled by tender-hearted hills and traversed by the placid waters of the Douro, on which since time immemorial have sailed those unique Rabelos laden with oaken barrels, bearing to the cellars of the city the precious nectar which, carefully bottled and elegantly labeled, will make its way to the furthest corners of the earth, enhancing the imperishable fame of one of the most highly prized wines on the face of the globe.

And readers of our newspaper know that this sad, mysterious and blood-curdling story relates to nothing less than a decapitated corpse: the pathetic mortal remains of a person unknown, horribly mutilated, abandoned by the murderer (or murderers) in a patch of waste land on the edge of the city, like a worn-out shoe or an old tin pan.

This, alas, is the turn things seem to be taking these days in this country of ours. A country which has only recently recovered democracy and has been accepted into the European Community along with the most civilized and progressive nations of the Old Continent. A country of honest and industrious folk, who return home of an evening weary from a hard day’s work and shudder as they read of the murky deeds which the free and democratic press, such as this newspaper, is unfortunately bound to report to them, even if with aching heart.

And it is indeed with aching heart, and in great perturbation of mind, that your special correspondent in Oporto is obliged by his professional ethics to tell you the sad, murky and blood-curdling story which he himself has lived through at first hand. A story which begins in one of the many hotels in this city, where your correspondent receives an anonymous telephone call. For like all journalists engaged on difficult cases he receives dozens of anonymous calls. He answers the telephone with all the skepticism of an old and experienced journalist, fully prepared for some mythomaniac intent on telling him that a certain councilor is corrupt or that the wife of the chairman of a certain sporting club is going to bed with a bullfighter.

But not this time: the voice is crisp and almost authoritarian, with a strong northern accent: a young voice, which might well be full of self-confidence if it were not speaking in an undertone. It tells your correspondent: the head is that of Damasceno Monteiro as errand-boy for the firm of Stones of Portugal, his home is in the Ribeira, Rua dos Canastreiros, I don’t know the number because there is no number on the building, it is opposite a fountain, you must inform the family because I can’t do it for reasons I wont go into, goodbye. Your correspondent is left speechless. He, an experienced, fifty year-old journalist who in the course of his life has witnessed the most appalling situations, must now take on the tragic, and at the same time Christian, task of bearing the mournful news to the victim's family. What to do? Your correspondent is fraught with misgivings, but he does not admit defeat. He knows that his profession calls even for such missions as these, painful but unavoidable. He goes down into the street, he hails a taxi and tells the driver to take him to Rua dos Canastreiros, in the Ribeira.

Читать дальше