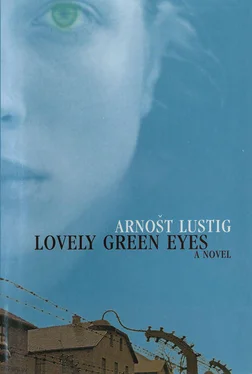

The repair work was directed by Obersturmführer Xaver Kinkel, a dwarfish man in a colonel’s uniform which made him look like a green gnome. He wore fur boots and a woollen ski mask on his face. A little man of indefatigable energy and organizational talent, he wore several Nazi decorations. He appeared to have sprung straight from a Dr Caligari film. All one could see of him were his bespectacled eyes.

Obersturmführer Kinkel knew how often similar disasters happened on the Ostbahn, the eastern track whose repair and maintenance — but not its security — he was responsible for. Not one of them had been an accident. He claimed no other merit for his work on the Ostbahn than that which a clockmaker would claim for repairing a broken timepiece. Those who threatened the Ostbahn threatened Reich property, the spirit of the Reich. Germany’s railways now seemed to him like a wounded, bleeding beast.

The matron organized blood donors. The Brown Nurses all volunteered. So did servicemen and women who’d come through the disaster unscathed. The matron got Skinny to bring out some chairs. Who knew their blood group?

Ginger, Maria-from-Poznan and Smartie had already volunteered. The matron noticed Skinny’s tattoo on her forearm. A number? Feldhure? She was shocked. Only then did Obersturmbannführer Mathilde Kemnitz realize where they were. This was the estate they’d heard about. She stopped being impersonal.

“Schämst du dich nicht?” Aren’t you ashamed of yourself?

Skinny shook her head at the nurse.

“She’s not one of us,” the nurse said.

“She passed my screening,” Oberführer S chimmelpfennig intervened. “She has Aryan blood.”

At least I hope so, he added to himself. In the chaos of Auschwitz-Birkenau or Festung Breslau the right hand didn’t know what the left hand was doing.

“Jawohl, Herr Oberführer” the matron said.

The Frog hung up an acetylene lamp by the gate. Out of the corner of his eye he saw the gilded tin eagle. A truckload of army engineers pulled up. They had come for sex, but the truck did not even enter the estate. Operations were suspended. The men could dismount, the truck would stay. They could wait in the waiting room. Was it warm in there? Yes, warm and there was music.

The Oberführer took the matron on a tour of the estate. He showed her the latrines, the kitchen, the guards’ dormitories, and where she would find drinking water. Skinny helped her until nine in the morning. She could scarcely stand. Finally Obersturmbannführer Kemnitz allowed her to go and lie down. The dormitory was full of soldiers. She stretched out in Cubicle 16 and fell instantly asleep. She dreamt that she was a Brown Nurse and that her train had been derailed. When a Hitlerjugend boy saw her blood he shouted that she was a Jewess. Her blood turned to water. Rats were crowding round her. She screamed when the heat from the fire got under her skirt. Her heels were burning, she was afraid she might lose her legs. Her stomach was aching. She tried to fight off the rats with her hands.

She was woken by the matron, who had heard her scream. The woman gave her a plate of tapioca pudding with a scattering of sugar and chocolate and a topping of raspberry juice. She put a little jug of milk before her. The first thing Skinny was aware of was diarrhoea. Was that why she’d had a bellyache in her dream? She ate faster than she wanted to in front of the matron.

“What are you afraid of? Do you have diarrhoea?”

“Sometimes.”

“From the food or from the cold?”

“I don’t know.”

“No wonder, in these conditions. All of us have it, out east.”

Then she said: “It happened so suddenly, in a matter of seconds. A colossal bang. Cases were flung about, people screamed. We were thrown from our bunks and seats, hitting other bodies. There was shattered glass everywhere. People were pushing and stumbling, stepping on each other. And at last the train came to a halt. We were lucky it didn’t happen on the bridge. Perhaps we were moving too fast. If it had happened on the bridge we would all have been drowned in the icy water.” She paused. “We came to the east to bring them civilization,” she continued. “To teach them German, get them used to German laws.”

Her voice broke. She watched Skinny eat, licking her plate clean and drinking the milk in big gulps. It was the first milk she had had for three years.

“No-one’s going to take it away from you,” the matron said. “And look what they’ve done,” she went on. “We were on our way to the front. They ought to shoot anyone getting close to the track. Surely the Ostbahn is ours? Who’s going to make up the loss? Doesn’t anyone guard the track? Where are our aircraft?”

“I am full of misgivings,” the matron said.

She raised her eyes to Skinny: “So few like us.”

Skinny needed to belch.

“It is Germany’s fate,” the matron said. Her neck wrinkled into folds that seemed to Skinny like a many-stringed necklace. Lines appeared on her forehead. In spite of her ample figure she was a good-looking woman.

Then she added: “Would you want it to happen all over again, seeing that you’re not German?”

After a while she asked, with her eyes on the ground: “How many?”

Skinny did not understand. Her short hair was stuck to her neck with sweat. She felt different now to how she had at the beginning of the night, more like an uninvited guest at someone’s feast. Or someone’s wake. She was aware of the pudding and milk in her stomach. Small amounts rose now and again to her mouth. It was pleasant, reminding her of food and of being full.

“How many soldiers each day?” the matron asked, explaining her question. “Those poor boys. My name’s Mathilde — Sister Mathilde or Frau Mathilde. On duty they call me Obersturmbannführer Mathilde.”

Her voice and gaze echoed the numberless sick, wounded and dying she had seen.

“Twelve,” Skinny said.

“Twelve?” Sister Mathilde repeated.

“Sometimes more.”

“Every day?”

“Except Sunday. But sometimes on Sunday too. Not today.”

“I saw the troops arrive. Will you have to catch up?”

“I don’t know. Perhaps.”

The matron reflected on the different lives that people were born to, how their fates differed. Her mother had also been a matron, just as her mother’s mother was before her. The Kemnitz matrons. It was a family tradition, a dynasty.

She looked at Skinny. Might she have become a nurse? She did not wish to know how a 15-year-old had become a whore in Germany.

“I wouldn’t have the stomach for it.” Then she asked: “Didn’t the Lebensborn organization have this place before?”

“So they say.”

It seemed to Skinny that there was distaste in the matron’s well-fed voice. And Skinny was right, the matron had a rather bourgeois view of fallen girls and of marital fidelity. She would not allow a man other than her husband to have anything to do with her body.

“You must have started early. You look very young. Fifteen?”

“Eighteen,” Skinny said. “Getting on for 19.”

“You did a good job,” said the matron.

Skinny didn’t answer.

Skinny had gulped her food down like a sick animal, afraid that someone might snatch it away. This aroused both suspicion and compassion in Obersturmbannführer Mathilde Kemnitz. And when, earlier on, she had kicked off her blanket and screamed in her sleep, the matron had noticed a festering sore on her bottom. For a moment she considered enrolling the girl in the Brown Nurses. Was she in the brothel as a punishment?

“Lie down on your tummy,” she ordered.

With her fingertips she probed the wound.

“Has the doctor seen this?”

“He gave me some sticking plaster.”

Читать дальше

![Корнелл Вулрич - Eyes That Watch You [= The Case of the Talking Eyes]](/books/32103/kornell-vulrich-eyes-that-watch-you-the-case-of-thumb.webp)