“You won’t believe this. In our camp we have a stove with a flue just like this one, and in the flue there’s a mouse. When we stoke the fire, the mouse hides. It’s got some hiding place in the wall, no-one knows where. As soon as the flue cools, the mouse begins to scratch. Bound to be a Jewish mouse. It’s not enough to have a will to live, or to dodge being burnt. This mouse must also be clever and lucky, or else it wouldn’t survive. Should humans learn from mice?”

He saw her blush but went on.

“I like it when you blush. As you can see, I find it hard to say goodbye to you. I’d love to take you out for a beer to the railway pub. I’ll see if they’ll let you out with me. They have Czech beer there. Tell me, are you corresponding with anyone?”

“No.”

“Would you like me to take a message to anyone? Give someone news of you?”

“Thank you, but no,” she said.

She dropped her eyes. She felt herself trembling. Why had he said “a Jewish mouse”?

He put his finger on her lips. He saw her alarm, her sudden start and her step back, but he didn’t show it. He didn’t want to frighten her even more. He was asking himself why it was so important to him to make a prostitute whom he had already had like him. Did she think that every Wehrmacht officer reported to the Gestapo?

“Would it break one of your private rules if you were to kiss me goodbye?”

She did so.

Then he said: “Anyway, it’s all schüssegal . Farewell.”

He picked up his yellow, elbow-length fur gloves. These probably hadn’t come from the Auschwitz-Birkenau store. He was suddenly irritated. He pulled on the gloves. So he was not going to shake hands with her? Had he gone too far? Had it just occurred to him how many dozen soldiers this thin, mournful little whore would lie with tomorrow, and then again, and after her Sunday break, on Monday, Tuesday and so on? Was he already thinking of his armour plated Horch? Of the provisions in its boot? Today he was here, tomorrow who could tell? That was the fate of an officer in wartime. To live from one hour to the next, from one day to the next. Exactly the way a whore lived.

She shrank. Her shoulders and head drooped. The hollows in his cheeks reminded her of how he had come to her cubicle, frozen. He was, she could see, already somewhere else in his mind. Before he closed the door she experienced a moment of panic at the thought that he might still trap her, surprise her or accuse her of something.

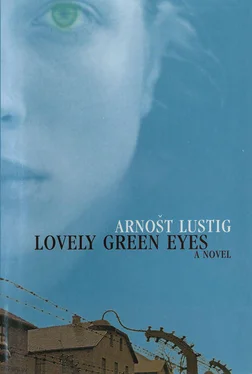

But he just said: “You’ve got lovely green eyes.”

He must have told Madam Kulikowa that because it remained with her. At No. 232 Ost they called her Lovely Green Eyes.

*

Fresh snow fell during the night. Black flakes were floating down to the ground; in the morning they would be white. Who could tell how Captain Daniel August Hentschel would get back to his unit in his bullet proof, four-seater Horch with chains on all its tyres? The snow glistened in the darkness. The water in the tubs no longer melted. The wood began to spit in the stoves.

“You’re crying?” Skinny asked.

“Not because of that,” Beautiful said.

This was the third day that Beautiful had diarrhoea. It was the first time she hadn’t talked about her mother.

“I’m thinking the same as you,” Skinny said.

“I’m thinking of my mother,” said Beautiful.

Twelve: Erich von Eicken, Albrecht Domin, Karl Osten, Varin Arp, Horst Torberg, Theodor Eisenbach, Herwart Kopf-Eschenbach, Hans Seidel, Endos Bredel, Berthold Wupperthal, Berndt Uhlstein, Max Edell.

They could tell the voices of the guards apart. The deep and even deeper ones, and the high and higher ones, like a children’s choir. Was it a sin that she thought of her young brother?

There had been a snowfall. Ginger and Maria-from-Poznan had started yard duty at 5 a.m. to clear the drifts around the latrine.

Skinny and Estelle climbed into one tub at the end of the corridor. Skinny sometimes had the impression that Estelle was avoiding her and at other times that she was seeking her out. She leant against the side of the tub, feeling the rotten wood against her back. Her body was aching, she felt as if she had been run over. Absentmindedly she splashed her face, then licked her lips.

“Don’t drink it,” Estelle said.

It was almost dark.

“I’ve had enough of it,” Estelle continued. “Haven’t you? Did you have that officer yesterday?”

Surely Estelle knew who she’d been with? Why did she ask? She had learned to lie. Her voice was matter-of-fact, but she was keeping something hidden.

The soap was coarse, rectangular double bars for laundry work, with grains of sand. The soap repeatedly slipped through her fingers and she had to retrieve it from the bottom of the tub. The Oberführer had told them that it was the same as was used by the troops. She got a splinter in her hand and immediately pulled it out. They were large splinters, and the larger they were the easier they were to get rid of.

“Aren’t you cold yet?” Estelle asked.

“Not really,” Skinny lied.

Was Estelle blaming her for having had only one man yesterday? Did the others have to make up the numbers? She did not make these decisions herself; Madam Kulikowa decided who was sent to her.

“I’ve learned to count the time, not the number of bodies,” Estelle said. “How many hours I still have left.”

That didn’t sound like a reproach.

“Yes,” said Skinny.

“It’s a shift, like the laundry women, coal miners, or the girls in the weaving shop. Like the girls in the bakery kneading dough.”

“Perhaps.”

“If somebody asked me what I’ve learned here, I’d say: To lie and to die.”

“We aren’t dead yet.”

“Twelve times a day,” Estelle repeated. “Today fifteen times. I don’t know where my family are or what has happened to them. My father, mother and sister. I drown it all in a lie.”

The water splashed. Estelle was not lying now. Skinny began to suspect what was behind Estelle’s confidences.

“I’d like to be able to handle it like going to work.”

Skinny looked at her. In Estelle’s voice rang an echo of what she heard within herself. Estelle had never spoken in this way about her family. Was it better to know that they were dead or to be tortured by the uncertainty that she heard in Estelle’s voice? No-one knew who they killed, who starved to death or who was lost somewhere. She had been putting off her questions and her doubts from the first day she got to Auschwitz-Birkenau with her family. Now this seemed far away and long ago, but it was neither.

The tubs stood about three yards from each other. It didn’t matter where each had come from, from what country or what region. Things vanished under a sea of ashes, of mud, of snow and ice, like abandoned islands in some nocturnal icy ocean. She washed herself thoroughly, everywhere, even the soles ofher feet. Who knew what she had stepped on when she came to the tub barefoot?

In the sixth tub someone was singing. Ginger?

Estelle washed herself with a large natural sponge which the truck from the Wehrkreis had brought. The men used them for washing the Oberführer’s car. Skinny’s ears were full of water. Estelle offered her the sponge.

“Thanks.”

“This soap is like sandpaper.”

In the yard outside, the troops, ready for departure, were singing a song about Hitler. She could hear the shout Heil three times, and again three times.

“They are pigs,” Estelle whispered.

Skinny was anxious not to catch something from the water when she had so far avoided infection from contact — or so she hoped.

“They think that we are the pigs. Me and you,” she answered.

Читать дальше

![Корнелл Вулрич - Eyes That Watch You [= The Case of the Talking Eyes]](/books/32103/kornell-vulrich-eyes-that-watch-you-the-case-of-thumb.webp)