Let the raven be a lesson to you, Saraqael had warned us bitterly, as though he were in competition with the birds himself: Be satisfied with what you have, however little, or you shall lose even that in vain hankerings and preposterous emulation.

With such words do angels of the Lord ensnare the ingenuous into contentment.

In corroboration of this truth, a raven met me, eye to eye. Envious bird to envious brother. Reluctant propagator to one who could not be certain he was meant to propagate at all.

Why, if my eye was open, the raven wondered, was I sitting quite so still?

In order, I answered, not to spill my brother.

The raven dropped his head on to one shoulder and eyed me with horizontal scorn.

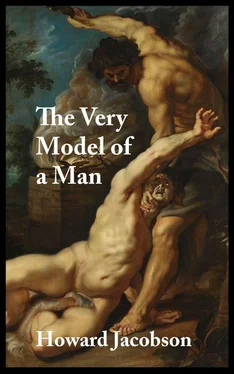

He knew something about death I didn’t. But then so did the meanest maggot I trod on in my garden. We had no experience of it among ourselves. No one had lectured us on the subject. No one had said whether we were built to go the way of Abel’s flock — a bleat, a gush of blood, and then up in smoke to please the nose of God; or whether life would drip out of us, in a crimson trickle, like wine from a punctured wineskin. We had been left untutored in mortality. I held Abel hushed and moveless in my arms to keep the life steady and irreducible within him.

The sky would not progress into darkness. The sun had gone, but everything else — moon, stars, wind, the black that normally superseded purple — hung in a suspense that was more respectful than expectant. An evening such as this, perhaps this very evening exactly, had been long awaited. And eventuation commands deference. A ghastly, formal surpriselessness spread inexorably into every corner of the night, like a last reprimand to doubters, like a proof too damning to be questioned, like the final reassertion of absolute power.

Only the ravens wondered what the long lingering of half-light held for them.

In time — although all usual measurement of time had stopped — the raven to whom I had confessed my ignorance of death began scratching in the soil. I took him to be after worms or shard beetles or some other vileness mirroring the mind of God, but conscientiously though he clawed, he never once looked to see what he’d unearthed, never once removed his gaze from mine. His expression was serious, reflective, fretful, not lacking in rapacity but requiring me to grasp that rapacity was not the first and last of his character. I also have it in me to be of use, the eye said. I am the enemy of angels, just like you. Learn, then, from me. Scratch, scratch, scratch as I do, and all may yet be well.

It was only then that it occurred to me that I had done something that needed to be hidden. Did I suppose, with the whole of heaven watching, that I could conceal my brother, as the bird advised, and go on as though nothing out of the ordinary had happened? Of course not. I knew how comprehensively I’d been observed. But I had at last to put Abel down. My arms were tired. He was tired. It was necessary that I lay him somewhere. And while I believed I was ready to withstand whatever questions the Holy Inquisitor was soon to hurl at me, I felt less confident about meeting the wailings of my mother and father. I could not say to them, as I could to Him, this is Your doing, for the reason that they were His doing too.

It was from them I had to hide Abel.

But I could not lay him in the earth.

The raven’s eye grew more livid. Scratch, it said, scratch if you value your immunity. Scratch if you value your good name. But how was I to tell a raven that I could no more claw the earth with my fingers than I could receive spittle from his throat?

Scratch, scratch, said the raven.

I cannot, replied the man.

Then my friends and I will do it for you, coward, scoffed the bird.

We sat in unblinking silence, we two brothers, and watched the ravens excavate. Their envious natures made them competitive. Jealous of the sharpness of one another’s beaks, they attacked the ground as though it were their enemy, perforating the soil with a ferocity that must have made the writhing worms beneath fear Armageddon had begun. We sat as still as owls, smelling dung and loam, listening to the breaking of beetles’ backs, the splintering of shields and shells, the juicy skewering of slugs. Until at last there was a shallow trench the size — the length and depth, the shape — of Abel.

Lay him down, said the raven.

I shook my head.

Lay him in, said the raven.

I shook my head.

Lay him on his back, so that he can look up towards the sky, said the raven, and we will cover him, my friends and I.

Only if you promise he will always see the sky, I said. Only if you promise you will never turn him over.

Trust us, said the raven. Lay him down, lay him in, lay him on his back, and we will hide him.

And so I did. And so they did. But the moment there was no more of him above ground — not one straggling hair remaining, no cruelly broken bone, no gentle outline showing through impressionable soil — I remembered I had failed to show a brother’s love, had not put my ear to his breathing in the one hour above all others when it mattered that my hearing should be infallible. Where had been the use of all those years of vigil if I were to prove careless now?

The ravens read my mind. Nothing is ever lost on the envious. For envy is the engine of intelligence. They hopped around the perimeter of the grave they’d made and dared me to unmake it. Scratch here, they said, and we will requite you, claw for claw.

I outstared and outwaited them. Disgusted by their own company, they grew impatient for the night that would not come, began to fear that elsewhere there were other birds doing better out of the interminable suspension of darkness than they were, and one by one — all except my bird — hobbled off, broken-footed and crooked-spirited, to sink their sight, if not their claws, into whatever thing they’d missed.

But when I raked the earth for Abel, he too was no longer there, and the soil was not warm from where he’d been.

Was this how we died? Did the ground below the ground open wide its mouth to receive our bones and swallow down our blood? Were we not available to be visited? Had I seen the very last of Abel?

The bird squinted at me, still astonished by how little I knew.

I called to God: Where is Abel my brother?

All at once the darkness which had been held in an unbearable abeyance, like thunder that would not break, fell around me. All shapes vanished. All solidity dissolved. There was no separating me from the blackness. It was as if space itself had been swallowed, just like my mother’s other child, in a single gulp. Only the raven’s eye gave out light.

I cried: What have You done? Where is my brother?

And God answered through the bird, saying: ‘Wouldst thou dare call unto Me! What hast thou done? The voice of thy brother’s blood have I listened to, and thy brother’s generations which thou hast denied. For their sake have I done what I will never again do, and opened the earth’s stomach to receive him. But thee will I not receive.’

Am I, of all people, not to be told what You have done with him? I demanded of the Lord. Am not I my brother’s keeper?

The livid eye narrowed and flashed, like a blade piercing the blanket of the night. The beak snapped shut, as though upon a fly, and then creaked open — a rusted gate emitting rusted sounds.

‘Thou couldst not keep what thou wert given, Cain. Instead thou didst what thou now must name. Speak it: What thou hast done!’

How far back, I wondered, how far back into the history of doing would He allow me to go. Against just such a question as He had put to me, delivered in just such a voice at just such an hour, I had long prepared my answer: Lord, I have done what You fashioned me to do. But I did not have the courage for it now, face to face with the dishevelled raven, blacker than the night wherein I stood and quaked, alone. Instead, I said: Lord of the World, for Whom the whereabouts of the finest grain of sand is certain knowledge, Who cannot be surprised by any thought, of whatever monstrous growth or vile complexion, that flowers in the mind of man — why do You ask to hear what You already know? You knew my deed before I did. Is it out of cruelty that You would make me name it?

Читать дальше