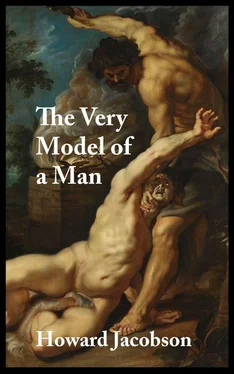

I left him on the ground, unharmed, and busied myself unnaturally at his altar. I didn’t look at him. I prepared the fire, lit it, shaped what was left of my unleavened cake mix into ten round wafers and arranged them on the griddle.

When he came at me he had the advantage of surprise, but not strength. He was too finely made.

You mustn’t, was all he said.

I held him off, my first concern being my offering which was now hallowed by struggle no less than sacrifice. Not only was it a gift against my nature, it was an offertory against my brother. We were both on that griddle. I hoped the gesture would be well received.

You mustn’t, he said again. And this time put his hands on me. It had been years since I’d last been rough with him. And now that I was rough with him again I discovered that I’d missed it, that it was no way for brothers to be, keeping each other at arm’s length, not touching, not fighting, not arguing, just silently denying each other’s right to be. We should have got to grips physically more often. It should have been ordinary with us, commonplace, an unexceptional event. Then we might have known better how to go about it. Might have found the sensuousness of it more resistible, less of a luxury.

All right — I might. It was on me that the charm of novelty fell. I smelled his bathed skin. I smelled his fear. I smelled his likeness to me. It’s always possible that I smelled his hatred and took it for something else. Hatred is the chameleon of scents and to survive must pass as bergamot or attar. When I pulled him close, I couldn’t be certain he was not my father, not my mother, not myself. Get very close and you lose a person altogether. This is universally true, but in my brother Abel’s case there is also his delicate framework to take into account. He almost fell apart in my arms. And when I began to punch him, not hard but persistently, first on one shoulder, and then another, first on this side, then on that, all that was ponderable in him, all that gave him weight — and all that lent density to his whiteness, all that was silver, all that was milk — fled his body.

I held him so that he shouldn’t fall or float away, and so that I could go on rhythmically striking him. Getting the rhythm right seemed to be important. It needed to be the rhythm of speech. A duplication of the patterns which I knew dispirited him. This was just talk, I must have wanted him to know. A continuation of our argument. The argument we never had.

I had to take him round the waist at last, supporting his spine for fear that, as he could not fall on me, he might choose the other way to go and break backwards. His face was tight against mine. Or at least someone’s face was. The lips twisted in what looked like the old family jeer — triumph when no issue had been contested, stealing what had been freely given — and more teeth showing than I cared to see. Marvellous, how teeth can express despair. The eyes were open but blank. No one’s eyes that I recognised. A bad odour came from him, whoever he was.

I let him go and he fell easily, almost comfortably, crumpling from the middle, his ankles crossed. I turned to my unleavened cakes but they were black and fuming, like the droppings of those three-eyed amphisbaenae that used to groan and vomit themselves into being in the days when the Lord had even less control over Creation than He did on this wild flaming yellow evening, painted to harmonise us with Grandeur.

A bad odour came from the altar too.

I looked back to Abel. I wanted to say, I hope you are pleased with yourself. But was so ashamed of him for lying there without weight or pigment, without fight, only a grimace of absurd concentration on his face, as though he were taking advantage of this quiet time to make his devotions, to give thanks where all his senses should have told him no thanks were owing; I was so angry with him for his compliancy, and so humiliated by his exposure, that I began to shovel debris on him, just dust at first, just grit and pebbles that I could kick, but then shale and flakes of slate, flint, chippings from the clumsy slabs of stone quarried by my father in slavish obedience to Saraqael’s instructions for a sacrarium and slaughter table.

A great dust rose from where he lay, as desolate as his altar. I could not penetrate it to see what damage I had done until the sun dropped like a stone itself into the earth, and a wind, smelling of salt desert, of drifting sand, of distance, blew the air from red to purple. I knelt by him and wiped the gravel from his eyes. His body had taken the main force of my attack; the only disfigurement to his face was a small cut running across his cheek like a broken vein. The idea that I had punctured his skin upset me more than any thought of what I had done to his bones. I couldn’t see his bones.

I cleaned the cut and then sat him up, putting my head to his chest as I had done for nights without number, crouched over his sleeping form, listening to the evenness of his breathing, keeping him from harm — but on this night there was no breathing to be heard.

Not from him, not from anything.

A short interval.

When they are greatly amused, or sorely distressed — and they are not always certain of the difference — audiences in Babel find that it settles their nerves to break, briefly, for refreshment and perambulation. A glass of iced water or sherbet, a turn beneath the steadying Babel moon, a quick exchange of pleasantries with friends, and they are once again ready to be entertained.

For those who prefer to stay in their seats and mop their foreheads with their sleeves, a divertissement is normally provided, not necessarily balletic, but always musical, light in spirits, and ironical if only by virtue of its incongruity to the main event.

Just like Naaman himself.

‘Going well,’ he says to Cain, off-stage.

Cain nods.

‘Oatcakes!’ Naaman shakes his head, has difficulty containing all the mirth that is in him. ‘Oatcakes! Wicked!’

Cain stares ahead.

‘So,’ says Naaman, as though Cain’s determination to make merry cannot be allowed to hinder the discussion of more serious matters indefinitely, ‘So, you are almost finished. You must be relieved.’

‘Were it not that the end is always a prelude to another beginning, I would be. As it is —’

‘Of course, of course,’ says Naaman. ‘Goes without saying.

But presumably you’ll be taking a rest. A deserved rest, if I may say.’

‘I have no specific plans,’ says Cain. ‘Naturally, I mean to discuss further engagements and other locations with you.’

Naaman puts his hand on Cain’s shoulder. A gesture implying willingness, concurrence, expansiveness beyond the scope of words. What he next says is so by-the-by, so much in the nature of an afterthought, that were he and Cain not such good friends he would probably not even bother to mention it. ‘This tower of yours —’

‘What tower of mine?’

‘This temple or whatever that you have a mind to rent or build or ruminate a while in…’

Cain risks continuing with not knowing what Naaman is talking about.

‘My daughter,’ says Naaman, not hiding that this is difficult for him, and not hiding that he is not grateful to Cain for making it so, ‘my daughter assures me that possession of an edifice enjoying elevation and solitude has long been an ambition of yours. I may have something that will answer.’

‘It has never been my intention,’ Cain says, ‘to climb on another man’s shoulders. If your daughter has told you I seek altitude for its own sake — to secure a view or to proclaim my eminence — she has either misled you or misunderstood me. I am not looking for a pedestal to perch on. I do, however, frequently think of a monument to my brother which will also serve as a resting place for myself.’

Читать дальше