to this world. Then arise from your corpse and go

Straight ahead regardless of the ghosts.

Know that those unfortunate beings exist only

When they trick you into believing that you exist, too.

Withstand, you must, the burden of death.

2.

In your dreams it is always

good to know that you are not you, and that you are far

from yourself. Neglected because you turned your attention

to the specters in your body. Do not connect yourself,

either through pain or joy, to the illusions of reality

so that you also will not exist as they do.

Disturbed by the morbid tone of the poem (about which more will be said later) and by the preparations to assassinate someone who had long been dead, Mrs. M. attempted to talk to her son, which caused an eruption of anger that ended in the above-described incident and Ernest’s admission to Professor Breuer’s clinic.

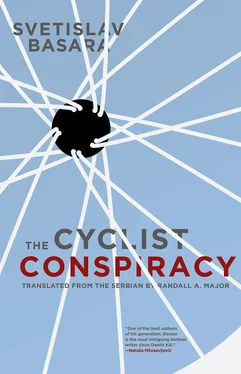

During our first meeting, Ernest left the impression of being a polite, well-adapted, but melancholic and above all introverted person. I must admit that this was the first and last time in my practice till now that I have met such a person. Except for the fact that he was unshakably convinced of absurd and illogical things, Ernest seemed to be a psychologically stable young man. It was quite difficult for me to penetrate the barrier that Ernest had placed between himself and the world; if it had not been such an interesting case I doubtlessly would have put it aside, because the patient showed absolutely no desire to be healed, which is the basic condition for the work of the psychoanalyst. However, Ernest showed much more interest and desire to cooperate whenever we began talking about dreams. In spite of that, he had great difficulty talking about what he had dreamt, not because he lacked education — quite evident from the texts in the notebook — but because of his hesitancy; he obviously did not want to betray his secret. I was present during the unusually interesting (but also slightly troubling) process of the split of Ernest’s personality into the personality of the Dreamer and the personality of the wakening Ernest, where the Dreamer personality — obsessed with delusions of holiness and edification — mostly neglected and later even despised the personality of the waking Ernest M.

When I told the patient that his spite was leading toward an even more drastic separation of his personalities, he reacted quite calmly. “Of course,” he said, “the old Ernest must die. In order for me to be born in the Spirit, I must get rid of the old Ernest. He likes girls, and women have the image of a soul instead of a soul.” To my question: What is that, the image of a soul? Ernest drew this sign  . I asked him to explain it to me and he agreed, with pleasure. What he ended up recounting to me was a flood of images from, I am convinced of it, the darkest regions of the collective unconscious. The female soul, according to Ernest’s account, is only an image of the male soul; it is Adam’s rib twisted, the archetype of the letter M, like mater ; hyle without form or substance. The male soul, on the other hand, has a horizontal cross-bar that gives it stability and it looks like this:

. I asked him to explain it to me and he agreed, with pleasure. What he ended up recounting to me was a flood of images from, I am convinced of it, the darkest regions of the collective unconscious. The female soul, according to Ernest’s account, is only an image of the male soul; it is Adam’s rib twisted, the archetype of the letter M, like mater ; hyle without form or substance. The male soul, on the other hand, has a horizontal cross-bar that gives it stability and it looks like this:  . But that is not its real state, but its state after the fall because, as can be seen, its top, all of its ends, are pointed toward the earth. Therefore it is necessary to turn things around ( metanoia? ) and point the soul toward the vertical axis anew —

. But that is not its real state, but its state after the fall because, as can be seen, its top, all of its ends, are pointed toward the earth. Therefore it is necessary to turn things around ( metanoia? ) and point the soul toward the vertical axis anew —  — so that it once again becomes receptive to taking in God’s energy which results in and creates the personality , enclosed by God in itself, a personality that no longer dies and can be represented graphically like this:

— so that it once again becomes receptive to taking in God’s energy which results in and creates the personality , enclosed by God in itself, a personality that no longer dies and can be represented graphically like this:

However, the real surprise came after the question was posed of how that came about. Ernest categorically refused to play any sort of role in formulating a pseudo-Gnostic theory of the soul. He claimed that he had received his teaching from reputable members of the mystical order he belonged to, but about which he did not want to say anything more intimate. This, we could call it “oneiric” education, had begun when he was just seven years old. Every evening when he would fall asleep, his teachers would appear and give him lessons about the meaning of life on Earth. To my question: Who were those men? he answered that he did not know because they had been dead since long before he was born, but he had recently identified one of them as Angelus Silesius. As his education advanced he, Ernest, experienced reality more and more like the sphere of chaos, and his dreams as the intermediary space between the material world and spiritual world, and he called that awakening . In my later study I established that Ernest had not had a chance to become familiar with eastern philosophy and the Buddhist religion, to which, apparently, the expression awakening refers. I was interested in how it was possible for him to be taught by people who had died several centuries before. Ernest said that, in dreams, such things had no meaning, which is true, because the dead often visit our dreams, though in a different function to be honest.

By pure accident, those days I got a letter from an acquaintance from the world of art, with whom I had kept up correspondence for a certain time.

“As you know,” my acquaintance wrote among other things, “the process of the maturation of the human being is closely connected with upbringing and education; we teach our progeny the secrets and rules of life. We do not do anything like that with dreams. We dream, if I may say it that way, chaotically, randomly. Perhaps that is why we live as we do in reality: in chaos, like straws given over to the elements.”

Those few remarks helped me to assemble an acceptable view of Ernest’s disturbance. It is true that we live in a chaotic world where the illusions of order and a system trudge about. Ernest’s sensitivity, fostered by his Calvinistic upbringing, could not stand the state of disorder, dominant in the world; added to that was the inability to change things. And that is why Ernest fled into dreams, a purely subjective place, in which he established a corresponding system of values, at the top of which God was found. The absence of his father (whom he did not remember), created tortuous complexes in him that he rid himself of by projecting them into the figure of Archduke Franz Ferdinand (the father of the nation=the father in general); in doing so, he killed two birds with one stone: he gained a father (a being without a father has no ontological backing) and he killed him at the same time (a being with a father has no independence), without exposing himself to any kind of risk because his father was already dead, brutally murdered.

Ernest, who became more communicative after seven or eight sessions, had a different version: Franz Ferdinand has to be killed because he was the inheritor of the Western Roman Empire which wants to control the Eastern — Byzantium. I reminded him that he thus brought about an aporia: Byzantium had not existed for centuries, and Franz Ferdinand had already been killed. But that did not confuse Ernest in the least: “Yes, doctor, the Archduke has been killed, but that was agreed upon just last year in October; I know that you will not understand me, but I will tell you anyway: the things that happen now are prepared in the future, it is a waste of time to seek for the causes of things in the past. Death does not come from the past, but from the future. As far as Byzantium goes, it never ceased to exist, it just went from being an exoteric empire to being an esoteric one. All sorts of states spring up on its soil, but the whole is never lost in parts; only parts are lost — the external ones.” I must admit that Ernest had mastered a certain logic, similar to Berkeley’s, that is hard to penetrate. Anyway, if by chance he had been born in the century when his imaginary teachers were, there is no room for doubt that he would have been a figure worthy of respect, judging by the wildness of his imagination, equal to Angelus Silesius. But chance wanted him to be born in the 20 thcentury from which he fled into the saving extra-territoriality of the Byzantine Empire.

Читать дальше

. I asked him to explain it to me and he agreed, with pleasure. What he ended up recounting to me was a flood of images from, I am convinced of it, the darkest regions of the collective unconscious. The female soul, according to Ernest’s account, is only an image of the male soul; it is Adam’s rib twisted, the archetype of the letter M, like mater ; hyle without form or substance. The male soul, on the other hand, has a horizontal cross-bar that gives it stability and it looks like this:

. I asked him to explain it to me and he agreed, with pleasure. What he ended up recounting to me was a flood of images from, I am convinced of it, the darkest regions of the collective unconscious. The female soul, according to Ernest’s account, is only an image of the male soul; it is Adam’s rib twisted, the archetype of the letter M, like mater ; hyle without form or substance. The male soul, on the other hand, has a horizontal cross-bar that gives it stability and it looks like this:  . But that is not its real state, but its state after the fall because, as can be seen, its top, all of its ends, are pointed toward the earth. Therefore it is necessary to turn things around ( metanoia? ) and point the soul toward the vertical axis anew —

. But that is not its real state, but its state after the fall because, as can be seen, its top, all of its ends, are pointed toward the earth. Therefore it is necessary to turn things around ( metanoia? ) and point the soul toward the vertical axis anew —  — so that it once again becomes receptive to taking in God’s energy which results in and creates the personality , enclosed by God in itself, a personality that no longer dies and can be represented graphically like this:

— so that it once again becomes receptive to taking in God’s energy which results in and creates the personality , enclosed by God in itself, a personality that no longer dies and can be represented graphically like this: