Some — just a couple — the guru does not touch. He withdraws his hand. “Not yet,” he murmurs, coldly. Imagine the feeling — to be refused the touch of the guru ! To be notably excluded — and in public! One of these sorry individuals is Akshay Kumar Sen. Akshay is tiny and dark skinned. He is not considered attractive. He is not young and plump and beautiful like the guru ’s favored boys. He is in his early thirties. He has lived a poor, hard life. But he is clever. He is diligently supporting himself as a tutor in Calcutta.

Akshay is desperate — needy. From his very first sighting of Sri Ramakrishna he is utterly besotted by him, but the guru , while unerringly polite, is always slightly cool and distant with Akshay. Many devotees are permitted to touch — even gently massage — the guru ’s feet, but the Master will not countenance Akshay’s touch. When Akshay approaches, he swiftly withdraws his feet with an exclamation of disquiet. Poor Akshay. He knows that the guru is perfectly capable of giving him the vision of Lord Krishna which he craves more than life itself, but for some reason he refuses to. Akshay tries everything he can think of to persuade the haughty guru —he is helpful and humble and obliging. He brings him gifts. The guru loves ice — the impoverished Akshay brings him an ice cream. The guru turns up his nose and will not touch it. Akshay endures endless snubs and rebuttals at the guru ’s hands. But every disciple is different. And Ramakrishna — ever inscrutable — is crushing Akshay’s ego through indifference. This is Akshay’s path. He will be rejected, ignored, passed over, humiliated. And even today, on this day, when everyone is touched, Akshay is held at bay.

In several written accounts of this landmark occasion, it is made clear that Akshay is rejected. In some, he is seen presenting a flower to the guru , even described as standing some distance away and then being genially called over by the guru and blessed. But the accounts of him being turned away have a greater ring of legitimacy to them. Sri Ramakrishna is not Jesus Christ. He is not democratic. He will not accept just any body. He is complex and discriminating. So let us imagine Akshay being turned away on that special day. And let’s ponder his sense of rejection, his feelings of inadequacy, of injustice; let’s dwell on his humility, his need, his poverty. Where, we wonder, may this whirlpool of emotions ultimately lead him?

A sour note has certainly been sounded on an otherwise magical day. But does it destroy Akshay’s faith in the guru ? Does it undermine his confidence in Sri Ramakrishna’s status as an incarnation? Nope. Not one bit. When the guru dies, Akshay remains one of his most ardent devotees, and after a while an urge rises within him to pick up a pen and to write about the guru . Akshay has no confidence — he is not well educated, he has not attended the university, he was never a favorite of Ramakrishna’s, not comfortably of the inner circle — but he picks up his pen and he begins writing down all his feelings of great love (underpinned, as they are, by this desperate sense of unworthiness, of unfulfilled desire), and creates an extraordinary landmark in the history of Bengali verse — a giant, crazy, stirring, magical, hysterical four-volume love song, a love rant to the guru : Sri Sri Ramakrishna Punthi.

And perhaps this is how the Master encourages Akshay’s sadhana —and in so doing, quite coincidentally, inspires his own great literary monument. Ramakrishna’s cruel rejection of this needy devotee only spurs on his ardor — nay, his idealism. Consummation can sometimes — just sometimes — be overrated. Which of us remembers the happy endings? Surely the poems of an unrequited lover are always the most passionate, the most moving, the most fierce, the most agonizing, the most heartfelt, the most indelible?

“When yearning for God,

Be just like the mother cow

Pursuing her calf.”

“Oh, that you were like my

brother,

Who nursed at my mother’s breasts!

If I should find you outside,

I would kiss you;

I would not be despised.

I would lead you and bring you

Into the house of my mother,

She who used to instruct me.

I would cause you to drink of

spiced wine,

Of the juice of my

pomegranate.…”

—Song of Solomon 8:1

The Rani. Ah, the glorious Rani — she started off this story, did she not? And now, at this late hour, she must be cordially deputized to end it (before it’s even truly begun).…

This is the Rani’s final scene. But it is two scenes. The Rani can never do anything by halves. She is a creature of many cuts, of many edits, of many versions. All that we can be sure of is that she is perfect, that she is noble, that she is a creature exquisitely of her time and out of it.

The Rani (the indignity!) has been struck down by chronic dysentery. Her doctors, fearing the worst, ask for her to be moved to more hospitable climes. Hospitable or no, the Rani opts for her garden house in Kalighat (adjacent to the famous temple), which stands on the banks of a small tributary of the holy Ganga.

Shortly before her death, as is traditional, the Rani is carried down to the banks of the river and partially immersed there. It is late at night and very dark, so many lamps have been lit. In one version of her death scene, a violent gust of wind blows them all out.

But the version we are following, the scene we are watching, sees the Rani blinking, owlishly, into the shining lights around her and then suddenly, furiously, impetuously, exclaiming: “Turn off the lights! Turn them off! I have no need of them! I have no need of artificial illumination now! Turn off the lights!”

Shortly after, embraced in the ebony arms of that coruscating darkness, with a small sigh of relief, a brilliant smile: “Ah, Mother,” she murmurs. “My Mother. Have you come?”

An indelible moment, I think you’ll all agree … (the sound-man conspicuously checks his watch). And how fortunate that we [The Cauliflower ™] were here to record it! What a coup ! Later, however (much later), when we anxiously scrutinize the footage, we discover that we have nothing ( nothing! not a damn thing!) in the can.

The Divine Mother — we know for an absolute fact; we are certain —has come herself, in person, to escort her favorite daughter into the heavenly hereafter. But the film? The film ?! Urgh . Completely blank.

Hmmm …

Perhaps, after all, we were just too close to see her.

“We have a little sister,

And she has no breasts.

What shall we do for our sister

In the day when she is spoken

for?

If she is a wall,

We will build upon her

A battlement of silver;

And if she is a door,

We will enclose her

With boards of cedar.

I am a wall,

And my breasts, like towers.…”

—Song of Solomon 8:8–10

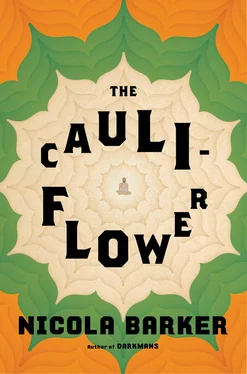

This novel (if I can call it that) is truly little more than the sum of its many parts. It’s a painstakingly constructed, slightly mischievous, and occasionally provocative/chaotic mosaic of many other people’s thoughts, memories, and experiences. I have not lived in the nineteenth century. I have never met Sri Ramakrishna. I am not a practicing Hindu. I have never visited Calcutta. If I had, I probably could not have written this book. I wouldn’t have been stupid, arrogant, brave, naughty — and possibly even dispassionate — enough.

This novel is a small (even pitiable) attempt to understand how faith works, how a legacy develops, how a spiritual history is written. I have been fascinated by Sri Ramakrishna for much of my life. He’s such a perplexing and joyous character. And I felt that his story might benefit from being told again — shared, enjoyed, celebrated (especially now) — but from a slightly new (and, yes, vaguely warped) perspective.

Читать дальше