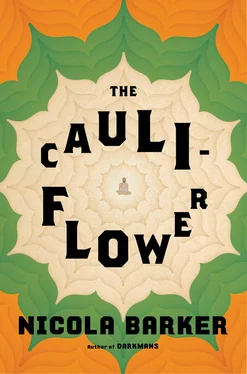

Nicola Barker

The Cauliflower

This small book is humbly and lovingly offered — like a freshly picked wild rose — at the feet of Shafilea Ahmed, Uzma Arshad, Mashael Albasman, Banaz Mahmod, and the five thousand other women worldwide who are killed, each year, for the sake of “honor.”

Not one, not two, not three or four,

but through eighty-four hundred thousand vaginas have I come.

I have come

through unlikely worlds,

guzzled on

pleasure and pain.

Whatever be

all previous lives,

show me mercy

this one day,

O lord

white as jasmine.

— Akkamahadevi, twelfth-century Indian poetess

Catch us the foxes,

The little foxes that spoil the

vines,

For our vines have tender

grapes.

— Song of Solomon, 2:15

1849, approximately

The beautiful Rani Rashmoni is perpetually trapped inside the celluloid version of her own amazing and dramatic life. Of course, every life has its mundane elements — even the Rani, beautiful as she is, powerful as she is, must use the bathroom and clean her teeth, snag her new sari with a slightly torn thumbnail, belch graciously with indigestion after politely consuming an over-fried rice ball prepared by a resentful cook at the house of her oldest yet most tedious friend — but Rani Rashmoni is, nevertheless, the star (the heroine) of her own movie.

How will it all end, we wonder? Temporarily disable that impatient index finger. We must strenuously resist the urge to fast-forward. Because everything we truly need to know about the Rani is already here, right in front of us, helpfully contained (deliciously condensed, like a sweet, biographical mango compote) within the nine modest words engraved in the official seal of her vast and sumptuous Bengali estate: “Sri Rashmoni Das, longing for the Feet of Kali.”

Hmmm.

Her husband, the late Rajchandra Das — a wealthy businessman, landowner, and philanthropist, twice widowed — first saw her as an exquisitely lovely but poor and low-caste village girl bathing in the confluence of three rivers thirty miles north of Calcutta. He instantly fell in love. She was nine years old.

That was then. But now? Where do we find the Rani today, at the very start of this story which longs to be a film, and eventually (in 1955) will be? We find her utterly abandoned and alone in her giant palace (the guards, servants, and family have all fled, at the Rani’s firm insistence). Her poor heart is pounding wildly, her sword is unsheathed, and she is bravely standing guard outside the family shrine room as a local garrison of vengeful British soldiers ransacks her home.

In one version of this story we find the Rani confronting these soldiers. In other versions her palace is so huge and labyrinthine (with more than three hundred rooms) that although the soldiers riot and pillage for many hours, they never actually happen across the Rani (and her sword) as she boldly stands, arm raised, fierce and defiant, just like that extraordinary Goddess Kali whose lotus feet she so highly venerates.

The Rani, like the Goddess, has many arms. Although the Rani’s limbs are chiefly metaphorical. And the two arms that she does possess — ending in a pair of soft, graceful, yet surprisingly competent hands — aren’t colored a deep Kali-black, but have the seductive, milky hue of a creamy latte. The Rani is modest and humble and devout. The Rani is strictly bound by the laws of caste. The Rani is a loyal wife. The Rani is a mother of four girls. The Rani is a cunning businesswoman. The Rani is ruthless. The Rani has a close and lucrative relationship with the British rulers of Calcutta. The Rani is a thorn in the side of Calcutta’s British rulers. The Rani is compassionate and charitable. The Rani always plays by the rules. The Rani invents her own rules.

The soldiers — when they are finally compelled to withdraw on the orders of their irate commanding officer (who has been alerted to these shocking events by the Rani’s favorite son-in-law, Mathur) — have caused a huge amount of damage. The Rani wanders around the palace, appraising the mess, sword dragging behind her, relatively unperturbed. She cares little for material possessions. Only one thing shakes her equilibrium. They have slaughtered her collection of birds and animals, worst of all her favorite peacock, her darling beloved, who lies on the lawn, cruelly beheaded, magnificent tail partially unfurled in a shimmering sea of accusing eyes.

1857, the Kali Temple, Dakshineswar (six miles north of Calcutta)

He is only four years older, but still I call him Uncle, and when I am with Uncle I have complete faith in him. I would die for Uncle. I have an indescribable attraction toward Uncle. It is painful to be parted from Uncle — even briefly. It was ever thus. And it is only when I leave his side — only then, when I am feeling sad and alone and utterly forlorn — that the doubts gradually begin to gnaw away at me. Perhaps I should never leave Uncle’s side, and then the doubts will finally be dispelled. Mathur Baba repeatedly instructs me not to do so, never to leave Uncle. (Uncle is a special case, Mathur Baba insists, a delicate flower who must be supported and nurtured at all times — and who else may perform this task if not I, his ever-faithful nephew and helper Hridayram?) I have great sympathy and respect for Mathur Baba’s views, but how can I always be with Uncle when I am constantly doing the work that Uncle cannot manage to do himself? Sometimes Uncle is unable to fulfill his duties in the temple and I must perform arati —the sacred worship — on his behalf. Sometimes Uncle sends me to the market for sweets (Uncle has an incredible sweet tooth) or on sundry errands. Even so, I guard Uncle jealously. I am Uncle’s shadow. But Uncle is slippery. He can be secretive. Uncle is not as other men.

The family jokes about how Uncle’s mother, Chandradevi, gave him birth in the husking shed at Kamarpukur. The old blacksmith’s daughter was acting midwife. She was sitting on a stool in the half darkness briefly catching her breath and then suddenly she heard the baby cry out. She leaped forward to take her first good look at the child. But he was nowhere to be found! She and Chandradevi — who is by nature a simple creature — were completely mystified. They both felt their way blindly around the shed until poor Uncle was finally located, hidden in the pit below the husking pedal. In many of our local Bengali folk songs the husking machine — the dhenki —is seen as a kind of phallic symbol. Uncle had fallen straight from one vagina into the deep, dark depths of another! Ah, yes. Looking back on it now it seems only right and natural that Uncle should eventually become a great devotee — perhaps even the greatest-ever devotee — of the Black Mother.

1793

Every story flows from a million sources, but the story of Rani Rashmoni (and therefore, by extension, the story of Sri Ramakrishna — as yet unborn, but already floating like a plump and perpetually smiling golden imp in the navy-blue ether) might easily be said to begin with a pinch of salt. Yes, salt. Sodium chloride. That commonplace, everyday, intensely mundane, yet still precious and once much-contested mineral. Salt.That most revolutionary of crystals.

If we cast our minds back, we see this powerful yet curiously delicate whitish-transparent grain generating ferment (ironically, saltis a preservative) worldwide throughout centuries. Saltis serious; it’s no laughing matter — didn’t we once look on in awe as the ancient Hebrews gravely made a covenant of saltwith their jealous God? And what of Christopher Columbus? Didn’t he voyage across the world (leaving in his wake that ugly colonial legacy — that despicable flotsam — of genocide, slavery, and plunder) financed, in the main, by Spanish saltproduction?

Читать дальше