Oh, I am late for tea! Please offer my copious love to Beatrice and Henry and do forgive this unforgivably abrupt finishing off.

With all good wishes,

or

“Namaste!”

Ms. Laura Bartholemew

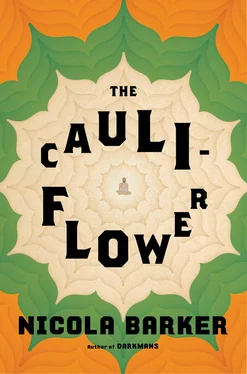

P.S. Papa, ever the natural scientist, wants me to be sure to assure you, for reasons of authenticity, that all the most important details of this curious little anecdote are absolutely true — the argument, the cauliflower etc., but for some perverse reason (known only to herself) the author of The Cauliflower™ (can we even truly call her “the author”? The collagist…? The vampire…? The colonizer…? The architect…? The plagiarizer…? The skid mark…?) has chosen to fictionalize this account.

x

LB

Girish Chandra Ghosh puts his beloved guru on the spot:

Girish, laughing, asked:

“Sir, are you man or woman?”

But he could not say.

Early autumn 1882. Jadu Mallick’s garden house

The guru (who will not be called a guru ) is in the sitting room, weeping copiously, having become perfectly demented with love for Narendra Nath Datta.

Late December 1883. The Dakshineswar Kali Temple

The Master (who will not be called Master) is in his room, collapsed on his bed, weeping copiously, still perfectly demented with love for Narendra Nath Datta. A bemused devotee, Bholanath, is holding his hand and trying to calm him:

Bholanath ( concerned ): “But is this appropriate behavior, Master? To become so distressed because of a simple Kayastha boy?”

Sri Ramakrishna ( briefly staunches his tears for a moment, thinks intently, hiccups, and then, at full volume ): “WAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAHHHH!!!”

Six months later

One of the devotees, Prankrishna, fondly known as the Fat Brahmin, tries to reason with Sri Ramakrishna (who is currently in the rather unfortunate habit of endlessly holding forth on the infinite virtues of Narendra Nath Datta) :

The Fat Brahmin ( nervously but respectfully ): “Father, if I might just … If I could possibly interrupt you for a moment … [ clears throat anxiously as Sri Ramakrishna — not much accustomed to being interrupted — gazes at him, hawkishly ] … Narendra is of course a lovely boy, but he has very scant education. Do you think it might be a little rash to be so — so infatuated with him?”

Silence .

Sri Ramakrishna continues to inspect Prankrishna, blankly.

The Master gazes at Narendra and sighs:

“When I hear you sing,

A snake hisses, spreads its hood,

Holds still, and listens.”

Several months earlier, the Master’s room, at the Dakshineswar Kali Temple (six miles north of Calcutta)

Sri Ramakrishna is surrounded by visitors and devotees, but he refuses to acknowledge any of them, only Narendra:

Narendra Nath Datta ( embarrassed ): “There are many people here to see you, sir. Do you think you might take the trouble to talk to some of them?”

Sri Ramakrishna ( glancing around him, perfectly astonished, as if they had all previously been quite invisible to him ): “Oh! [ dazedly scratches head ]…”

Two months later, the Master’s room, at the Dakshineswar Kali Temple (six miles north of Calcutta)

An exasperated Narendra Nath Datta sharply chastises the mooning and love-struck guru , warning him that if he doesn’t gain some control over his adolescent ardor he will be in serious danger of damaging his reputation.

The startled and deeply hurt guru goes scuttling to the temple and prays to the Mother, then returns, a short while later, in high dudgeon:

Sri Ramakrishna ( hotly ): “You rascal! For a moment you almost had me doubting myself, but then the Mother told me that what I truly love is only the God in you. Without the God in you I could not love you at all !”

Narendra Nath Datta laughs, bemused.

“Shame, hatred, and fear

Must be removed from your heart

Before you’ll see God.”

“I have taken off my robe;

How can I put it on again?

I have washed my feet;

How can I defile them?

My beloved put his hand

By the latch of the door,

And my heart yearned for him.

I arose to open for my beloved,

And my hands dripped with

myrrh,

My fingers with liquid myrrh,

On the handles of the lock.…”

—Song of Solomon 5:3–5

The guru openly and happily confesses:

“Really and truly

I have no pride — not any—

Not the slightest bit!”

1886. A nameless street. A nameless town. Bengal.

When I consider it, I cannot fully comprehend it. I cannot comprehend that Uncle is no longer here by my side, that Uncle is no longer with me. Because Uncle is my every word. Uncle is my every breath. Where is Hridayram without Ramakrishna? Where is Hridayram without Uncle? I am torn apart. I am empty. I am a pair of hands with nobody to serve.

And what was my crime? I had offered sandalwood paste and flowers at the feet of Trailokya’s daughter. Trailokya is the temple owner. His daughter was a sweet child, only eight years of age. I had seen her in the temple during arati and was suddenly inspired. I took her and I worshipped her following the ancient Tantric rites. No harm was done. But later the owner’s wife saw signs of sandalwood paste upon her daughter’s pretty feet and became enraged. She is a small-minded woman. She is wealthy but ignorant. She thinks that for a Brahmin priest to worship a girl child of a lower caste in this manner is an ill omen — that the child’s future husband will now die after her marriage.

But I meant no harm by it. Uncle is my example. Uncle is always my example. Did not Uncle say that social and caste rules were only to be maintained until we are able — with God’s help — to move beyond them?

It was the act of a mere moment, but the punishment was swift and harsh. Hridayram was told to leave the temple grounds and never to return. He quickly ran to his Uncle. He told his Uncle what had happened. His Uncle said nothing. His Uncle did nothing. His Uncle was a stone, a clod of earth. What could his Uncle do? What could his Uncle say? Hridayram turned and left. A short while later a temple administrator asked Uncle to leave as well. Uncle did not object. He just quietly picked up his towel, placed it over his shoulder, and commenced slowly walking toward the temple gate. Uncle did not argue. Uncle did not fuss. Uncle did not look back. And that was all. Uncle took Trailokya only his towel. Surely Uncle is the pinnacle of detachment and renunciation! But Hridayram is not like Uncle. Hridayram had grabbed what he could. No. I am not like Uncle. But surely this is because I care for Uncle! I must worry and think and plan ahead; I must plan ahead for Uncle.

Oh, when my fugitive eyes saw Uncle walking toward the gate, my heart was lifted. Suddenly there was hope! Yet before Uncle had reached the gate, Trailokya — apprehending Uncle’s stately movements — hurriedly came to remonstrate with him. “Sri Ramakrishna!” he exclaimed. “This is a terrible misunderstanding.”

“Have you not ordered me to leave?” Uncle asked. There was no anger in Uncle’s voice, only calm, only flatness.

“No, sir, no. It is only your nephew I have asked to leave,” Trailokya insisted. “I have not asked you to leave, Father. You can stay; you must stay. Please, Father, please, promptly return to your room.”

At this, Uncle smiled, then he turned, still smiling, his towel still over his shoulder — the very image of detachment — and began walking, slowly walking, back to his room again.

Читать дальше