Mother Teresa sees God (or Jesus) in all of the hopeless. When she dresses a gangrenous limb, or cleans up a pile of vomit, she is serving God in man.

It’s worth noting that in 2010 plans were under way to upgrade the legendary but severely dilapidated burning ghat at Nimtala. The great Bengali Renaissance poet Rabindranath Tagore was cremated there. They built a small monument in his honor. It was thought that it might be nice to change the name of the ghat as a mark of respect. Although when we look back to the original name — Nimtala — we discover that its origins are in the old neem tree which stood on that very spot for many centuries, and under whose holy and welcoming shade, it just so happens, Job Charnock first landed in Kolkata — which was not even yet Calcutta — on August the 24th, 1690.

Sometimes, when you read the assorted literature on the subject, it feels as if Mother Teresa (does she take her prefix from Ma Kali, we wonder?) was the first person ever to invest any concerted energy in Calcutta’s lost and her dying. But what of the Rani’s home? Where was it, exactly? Who ran it? And what did it consist of? History is hoarse — it has no proper voice to tell us. But what we can be quite certain of is that these are two women — two good, clever, inventive, powerful women — working, together, in Calcutta, under Ma Kali’s forbidding glare. They are creating a legacy shaded by the Paramahamsa ’s great white wings — of faith and unity and tolerance and service and care.

How curious, to have two great saints in such close proximity! What does this tell us about Calcutta, I wonder? Perhaps only that it is a place most in need of faith. In need of hope. A lost place. A hungry place. A desperate place. A city run under the brutal, clear-eyed, and merciless auspices of the Goddess Kali. The creatress, the destroyer. The mother, the murderess.

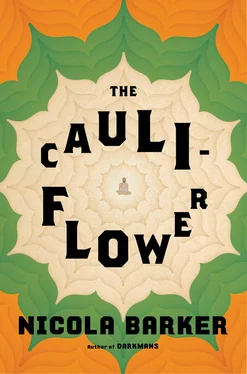

And this is enough (isn’t it?). Enough of Mother Teresa? For this book? For the Cauliflower ™, with its bad haiku and its sketchy budget? Simply to know that she was there? That sixty-two years after the main event this tiny, industrious, inventive, creative, ferocious, prune-faced saint came along and took a low bow? Isn’t that enough?

Yes?

Yes?

Although there is a bizarre footnote.… Because one thing we now know, much to our consternation — to our astonishment — of this blue-tinged saint (unlike her so recent predecessor, whose servant she quite unwittingly named her Home for the Dying after), is that while he was overwhelmed by the presence of God, she was signally under whelmed by it. This great modern heroine, this mysterious power, this taut nerve of a woman who was driven almost to distraction by her urge to serve, to save, was actually without God. But nobody — aside from her spiritual confessor — knew it. Because such was her love of God that she made an oath to live and serve without him. Without solace. Without comfort. Without inner peace. She gave it up. She sacrificed it. And more to the point, her God took it. He snatched it away from her. He left her dry and alone. Empty. Hollow. A spiritual husk. And so she became — in her own words — a saint of darkness. A black hole. And she gave up any hope, any comfort (“consolation,” the religious call it) for a period approximating — her secret oath promised— infinity itself . To serve. To inspire. She gave up her very soul for all eternity, to live without love, for love.

And why? Because she loved God so much. And in her beautifully, crazily warped conception of it, a true saint — a great saint — always humbly sacrifices the thing that she loves the most.

Ah, the Pair of Opposites!

I give you two saints:

One quite bloated with God’s love—

And the other? Starved .

1864, at the Dakshineswar Kali Temple (six miles north of Calcutta)

There is so much great potential in Uncle, and very often it saddens me that Uncle seems determined not to make full use of it. Late in his Tantric sadhana , Uncle secretly confessed to me that he was now possessed of the Eight Miraculous Powers. I became most excited at this news. Uncle could — if he wished — reduce his body to the size of an atom, or have ready access to any place on earth, or realize whatever his heart desired.…

Of course, armed with such valuable information I at once set about thinking of many interesting and lucrative ways in which Uncle might make good use of these new powers of his, and Uncle — with his habitual childlike spirit — was at first very enthusiastic about my many schemes. But then, after a little while, he became uneasy and restless and said that he would go to the temple and pray to the Goddess to find out which acts she wished to see him perform with them. When he returned from praying Uncle was very grave and sober. “The Goddess has told me that I am to hold these new powers of mine in as much esteem as I would hold excreta,” he said. From that moment onward Uncle refused to talk of such matters with me any further. And if I dared to raise them with him — and sometimes it was hard for me to resist — he would become quite incensed.

At another time Uncle caught me deep in conversation with Mathur Baba, who had inquired about the best way in which he might secretly leave his vast inheritance to Uncle. Mathur Baba and I were coming up with all manner of excellent plans when Uncle happened to enter the room, and — even though our talk immediately stopped — he somehow caught a whiff of what was being discussed (Uncle has a great talent for the reading of minds — this is one of his Eight Miraculous Powers, after all) and became instantly furious. He accused us both of trying to ruin him and then ran away almost in tears.

I wish Uncle knew what was best for him.

I wish Uncle knew what was best for us.

Mathur Baba loves to spend his money on Uncle in any way that he can. He once bought Uncle an exquisite Vaishnava shawl and presented it to him. Uncle — with the spirit of a child — took the shawl and felt its quality and admired its decoration and arranged it across his shoulders and twirled around his room in it. He was quite delighted with the gift. And so he went out into the temple grounds and pranced around in his new shawl, showing it to anyone and everyone who would care to stop and take a look. His moon face was beaming with joy and excitement. It was truly lovely to see him taking such innocent pleasure in Mathur’s generous gift.

But then Uncle’s mood suddenly changed. He began to scowl. “Tell me, Hriday,” he murmured, plucking at the shawl nervously, “will this beautiful shawl bring me any closer to God?”

Oh, how was I to answer him? My heart sank. I glanced away. I said nothing. And then before I could stop him, Uncle had ripped the shawl from his shoulders and had thrown it onto the ground and was spitting on it, with hatred, and then began jumping up and down on it. Next he ran off to find a match so that he might burn it — this hateful shawl, this beautiful shawl, this expensive shawl — because it could not bring him closer to God. No. Worse even than that. Because Uncle felt that to love earthly possessions — to feel such attachments — was to be drawn further away from God.

I am only thankful that Uncle was gone for some time trying to find a match so that I could take the shawl and hide it from him.

You might be forgiven for thinking that Mathur Baba would be cross with Uncle for treating his generous gift so shabbily, but Mathur Baba, on being told of what Uncle had done, just nodded his head approvingly. “It is perfectly right that your Uncle should have behaved as he did.” He smiled. Because Mathur Baba can find no fault in Uncle. Which I suppose is just as well — for us all.

Читать дальше