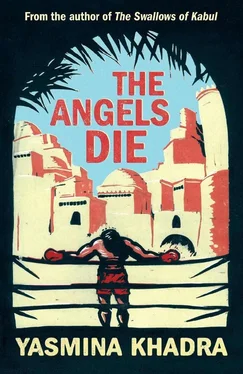

Yasmina Khadra

The Angels Die

My name is Turambo and they’ll be coming to get me at dawn.

‘You won’t feel a thing,’ Chief Borselli reassures me.

How would he know anyway? His brain’s the size of a pea.

I feel like yelling at him to shut up, to forget about me for once, but I’m at the end of my tether. His nasal voice is as terrifying as the minutes eating away at what’s left of my life.

Chief Borselli is embarrassed. He can’t find the words to comfort me. His whole repertoire comes down to a few nasty set phrases that he punctuates with blows of his truncheon. I’m going to smash your face like a mirror , he likes to boast. That way, whenever you look at your own reflection, you’ll get seven years of bad luck … Pity there’s no mirror in my cell, and when you’re on death row a stay of execution isn’t calculated in years.

Tonight, Chief Borselli is forced to hold back his venom and that throws him off balance. He’s having to improvise some kind of friendly behaviour, instead of just being a brute, and it doesn’t suit him; in fact it distorts who he is. He comes across as pathetic, disappointing, as annoying as a bad cold. He’s not used to waiting hand and foot on a jailbird he’d rather be beating up so as not to lose his touch. Only two days ago, he stood me up against the wall and rammed my face into the stone — I still have the mark on my forehead. I’m going to tear your eyes out and stick them up your arse , he bellowed so that everyone could hear. That way you’ll have four balls and you’ll be able to look at me without winding me up … An idiot with a truncheon and permission to use it as he pleases. A cockerel made out of clay. Even if he rose to his full height, he wouldn’t come up to my waist, but I suppose you don’t need a stool when you’ve got a club in your hand to knock giants down to size.

Chief Borselli hasn’t been feeling well since he moved his chair to sit outside my cell. He keeps mopping himself with a little handkerchief and spouting theories that are beyond his mental powers. It’s obvious he’d rather be somewhere else: in the arms of a drunken whore, or maybe in a stadium, surrounded by a jubilant crowd screaming their heads off to keep the troubles of the world away, in fact anywhere that’s a million miles from this foul-smelling corridor, sitting opposite a poor devil who doesn’t know where to put his head until it’s time to return it to its rightful owner.

I think he feels sorry for me. After all, what is a prison guard but the man on the other side of the bars, one step away from remorse? Chief Borselli probably regrets his overly harsh treatment of me now that the scaffold is being erected in the deathly silence of the courtyard.

I don’t think I’ve hated him more than I should. The poor bastard’s only doing the lousy job he’s been given. Without his uniform, which makes him a bit more solid, he’d be eaten alive quicker than a monkey in a swamp filled with piranhas. But prison’s like a circus: on one side, there are the animals in their cages and, on the other, the tamers with their whips. The boundaries are clear, and anyone who ignores them has only himself to blame.

When I’d finished eating, I lay down on my mat. I looked at the ceiling, the walls defaced with obscene drawings, the rays of the setting sun fading on the bars, and got no answers to any of my questions. What answers? And what questions? There’s been nothing up for debate since the day the judge, in a booming voice, read out what my fate was to be. The flies, I remember, had broken off their dance in the gloomy room and all eyes turned to me, like so many shovelfuls of earth thrown on a corpse.

All I can do now is wait for the will of men to be done.

I try to recall my past, but all I can feel is my heart beating to the relentless rhythm of the passing, echoless moments that are taking me, step by step, to my executioner.

I asked for a cigarette and Chief Borselli was eager to oblige. He’d have handed me the moon on a platter. Could it be that human beings simply adjust to circumstances, with the wolf and the lamb taking it in turns to ensure balance?

I smoked until I burnt my fingers, then watched the cigarette end cast out its final demons in tiny grey curls of smoke. Just like my life. Soon, night will fall in my head, but I’m not thinking of going to sleep. I’ll hold on to every second as stubbornly as a castaway clinging to wreckage.

I keep telling myself that there’ll be a sudden turnaround and I’ll get out of here. As if that’s going to happen! The die is well and truly cast, there’s not much hope left. Hope? That’s one big swindle! There are two kinds of hope. The hope that comes from ambition and the hope that makes us expect a miracle. The first can always keep going and the second can always wait: neither of them is an end in itself, only death is that.

And Chief Borselli is still talking nonsense! What’s he hoping for? My forgiveness? I don’t hold a grudge against anyone. So, for God’s sake, shut up, Chief Borselli, and leave me to my silences. I’m just an empty shell, and my mind is a vacuum.

I pretend to take an interest in the bugs running around the cell, in the scratches on the rough floor, in anything that can get me away from my guard’s babble. But it’s no use.

When I woke up this morning, I found an albino cockroach under my shirt, the first I’d ever seen. It was as smooth and shiny as a jewel, and I told myself it was probably a good omen. In the afternoon, I heard the truck sputter into the courtyard, and Chief Borselli, who knew , gave me a furtive glance. I climbed onto my bed and hauled myself up to the skylight, but all I could see was a disused wing of the prison and two guards twiddling their thumbs. I can’t imagine a more deafening silence. Most of the time, there have been jailbirds yelling and knocking their plates against the bars, when they weren’t being beaten up by the military police. This afternoon, not a single sound disturbed my anxious thoughts. The guards have disappeared. You don’t hear their grunting or their footsteps in the corridors. It’s as though the prison has lost its soul. I’m alone, face to face with my ghost, and I find it hard to figure out which of us is flesh and which smoke.

In the courtyard, they tested the blade. Three times. Thud! … Thud! … Thud! … Each time, my heart leapt in my chest like a frightened jerboa.

My fingers linger over the purple bruise on my forehead. Chief Borselli shifts on his chair. I’m not a bad man in civilian life , he says, referring to my bump. I’m only doing my job. I mean, I’ve got kids, d’you see? He’s not telling me anything new. I don’t like to see people die , he goes on. It puts me off life. I’m going to be ill all week and for weeks to come … I wish he’d keep quiet. His words are worse than the blows from his truncheon.

I try and think of something. My mind is a blank. I’m only twenty-seven, and this month, June 1937, with the midsummer heat giving me a taste of the hell that’s waiting for me, I feel as old as a ruin. I’d like to be afraid, to shake like a leaf, to dread the minutes ticking away one by one into the abyss, in other words to prove to myself that I’m not yet ready for the gravedigger — but there’s nothing, not a flicker of emotion. My body is like wood, my breathing a diversion. I scour my memory in the hope of getting something out of it: a figure, a face, a voice to keep me company. It’s pointless. My past has shrunk away, my career has cast me adrift, my history has disowned me.

Chief Borselli is now silent.

Читать дальше