Paraiti entered Harrison’s and went over to look at the bolts of fabric. She felt she was in a magic land of laces, silks, wools, calicoes, twills and cottons. The colours were stunning — shimmering blues, glowing yellows and bright reds. A senior saleswoman appraised her as she came in and immediately approached her. ‘May I help you?’ she asked. There was no accompanying ‘Madam’ to her enquiry, but Paraiti’s self-confidence had grown — and she had been to Harrison’s before and she knew the kawa, the protocol:

1. Shop attendants were always supercilious but they were, sorry lady, only shop assistants, even if they were senior saleswomen.

2. She had as much right as anybody else to shop in Harrison’s.

3. Her money was as good as anybody else’s.

She unpinned her hat and placed it on the counter, claiming some territory. ‘Why, thank you,’ she said pleasantly, revealing her scar in order to intimidate the saleswoman. ‘I’d like to see that bolt of cloth and that one and that one,’ and she pointed to the ones that were highest in the stacks.

Meantime, Paraiti rummaged through some of the other fashionable material and accessories that were on display. By the time the saleswoman returned, she had made her selection: a variety of attractive lengths of fabric, bold, with lots of flash. She also selected a couple of pairs of bloomers with very risqué ruffles on the legs. Pleased with her purchases, Paraiti waited at the doorway for the final piece of kawa to be observed:

4. When the paying customer is ready to depart, the door is always opened for her.

In a happy mood, humming to herself, Paraiti made her way back to the Regent, window shopping on the way, and took her seat in the theatre. Unnoticed, the Maori maid, who had been watching Paraiti in the haberdashery, and had followed her back, took a seat a few rows back.

Paraiti loved nothing better than to sit in the dark where nobody could see her and get caught up in the fantasies on screen. She had seen Charlie Chaplin’s previous movie, The Kid , and hoped that The Gold Rush would be just as good — and it was. The audience in the Regent couldn’t stop laughing. Paraiti thought she would die — the tears were running down her face at the part where the starving man in the film kept looking at the little tramp and imagining seeing a nice juicy chicken. And she just about mimied herself when the little tramp was in the pivoting hut caught on the edge of a crevasse; the hut see-sawed whenever Charlie walked from one side to the other. At the end she wanted to clap and clap: Charlie Chaplin was the greatest film clown in the world. She was so glad that she had come into town.

But when she came out of the theatre into the mid-afternoon sun and saw the Maori maid standing in the sunlight like a dark presence, she felt as if somebody had just walked over her grave.

‘You are Paraiti?’ the maid asked. She was subservient, eyes downcast, her years weighing her down — but her words were full of purpose. ‘May I trouble you for your time? I have a mistress who needs a job done. If you accept the job, you will find the price to your liking.’

Although everything in her being shouted out, ‘Don’t do this, turn away’, Paraiti equivocated. She had always believed in fate, and it struck her that coming to Gisborne ‘just like that’ might not be coincidental. She found herself saying, ‘Kei te pai, all right. Let me drop my parcels off at the municipal stables and then I will give your mistress an hour of my time.’

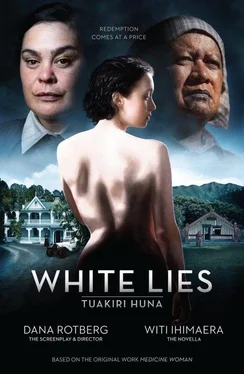

That task accomplished, the Maori servant introduced herself. ‘My name is Maraea,’ she said. ‘My mistress is Mrs Rebecca Vickers. The Honourable Mr Vickers is currently in Europe on business. We are only recently arrived in Gisborne. Be good enough to follow me, but stay far enough back so that people do not know that we are together.’

Paraiti was immediately offended, but it was too late — she had already agreed to speak to Mrs Vickers. She followed Maraea into the Pakeha part of town. The houses on Waterside Drive, ranged along the river with willow trees greening along the banks, spoke of elegance and quality.

Maraea waved Paraiti to join her. ‘The Vickers’ residence is the fourth house along, the two-storey one with the rhododendron bushes and wrought-iron gate. When we arrive at the house I will go in and see if it is safe for my mistress to see you. Kindly do not approach until I signal to you with my handkerchief.’

‘What have I got myself into?’ Paraiti wondered. Increasingly irritated, she watched Maraea walk towards the house, disappear and, after a minute or so, return to the street and wave her handkerchief. Paraiti approached the house and was just about to enter through the gate when she heard Maraea whisper from the bushes: ‘Do not come in through the front entrance, fool. Go around to the side gate, which is where such folk as you and I must enter. I will open the back door for you.’

Paraiti continued to the side gate. She opened it and walked along the gravelled pathway. A Maori gardener at work in the garden tipped his hat to her. Maraea stood at the doorway to the kitchen.

‘Come in,’ she urged Paraiti. ‘Quickly now. And you,’ she said to the gardener, ‘Mrs Vickers is not pleased with the way you have trimmed the lawn. Do it again.’

Paraiti followed Maraea through a long corridor to the front of the house. The sun shone through the crystal glass of the front door. The entrance was panelled with polished wood and lined with red carpet. A tall clock ticked in an oak cabinet against one wall. A huge oval mirror hung on another wall. A small table with a visitors’ book and a vase of lilies stood in the curve of the stairway to the first floor. Hanging from the ceiling was a crystal chandelier.

‘Be kind enough to take off your hat,’ Maraea said.

She led Paraiti up the stairs and ushered her into a back sitting-room. ‘Mrs Vickers will see you soon.’

‘Come away from the window.’

Paraiti had been in the sitting room a good ten minutes before Mrs Vickers arrived. The room showed all the trappings and accoutrements of a prosperous Pakeha merchant. The green velvet curtains were tied back with gold tassels. Antique chairs fitted with gold damask cushions were arranged around small card tables; the room was no doubt used as an after-dinner smoking-room by the gentlemen, or a place where the ladies could congregate in the afternoons to chat over cards. To one side was a fireplace, with a beautiful chaise longue in front of it. The decorations had an Oriental look — as if the Honourable and Mrs Vickers had spent some time in the East — and on the mantel above the fireplace was a photograph of a smiling couple, a young wife and her husband, standing with an Indian potentate. Electric lights in decorative glass lampshades were set into the walls, and everywhere there were mirrors. Paraiti had gravitated to the window, and was looking out at the garden below.

Turning, she immediately became disoriented; the hairs prickled on the back of her neck. In all the mirrors a young woman was reflected — in her mid-twenties, with red hair, tall and slim, and wearing a beaded mauve dress. But which was the woman and which was her reflection? And how long had she been standing there?

On her guard, Paraiti watched as the woman approached her. She was pale, beautiful. Her hair had been tinted with henna and her skin was glazed to perfection; her eyes were green, flecked with gold, the irises large, mesmerising and open. Paraiti resisted her hypnotic gaze, and immediately the woman’s irises narrowed. Then she did something perfectly strange — seductive, almost. She cupped Paraiti’s chin, lifted her face and clinically observed and then touched the scar.

Читать дальше