‘Afterwards I wondered about her remark. More intriguing was when she cupped my face in her hands and traced my chin.

‘“How pleased I am that you have found a good husband,” she said. Then she kissed me lightly on the cheek.

‘“Leb wohl, mein Herz. Go well, sweetheart.”’

Donald put the diary down.

‘You know …’ he began, ‘that diary entry has always puzzled the family. The Maori woman seemed to be acquainted with the lives of Marzelline and Rocco. How?’

He was looking at me, but I shrugged my shoulders and kept my silence.

Then Donald told me that at Marzelline’s death a locket containing dark hair was buried with her. ‘We’ve always believed it belonged to the Maori boy that Great-grandmother met while she was on Peketua Island with her father,’ Donald said carefully.

All along I’d told Donald that I was a descendant not of Eruera but of a person whom he took to be a separate identity, Erenora. How could I tell him that Eruera hadn’t been the person Marzelline thought he was? That he hadn’t died?

Should I tell Donald the truth? Or should I maintain the fiction? Such a moral dilemma! Even though I was only an amateur historian, did I not owe it to history to tell the truth?

I realised that Rocco himself offered an answer. He had obviously not told his impressionable young daughter that the boy had been, in fact, a woman. Perhaps Rocco had loved Erenora also. If it was good enough for Rocco to keep the secret out of love for his daughter, I would too. And Erenora, as well, she had chosen not to disclose the truth when she met Marzelline on that spring day in 1914 and, as you know, I love my ancestor.

Wasn’t that what history was, after all? A matter of perspective, determined by whoever told it? Even if it wasn’t, surely it was better for me to leave Donald’s family with the story of a Maori boy who was Marzelline’s first love and, from the sound of it, had held her heart always?

Wasn’t it their history, not mine?

‘Well?’ Donald asked. ‘So who was the woman Great-grandmother Marzelline met that day?’

The coals crackled in the grate. The flames flickered and then settled into a warm glow as I told Donald the truth.

I have always loved political opera, in particular Ludwig van Beethoven’s Fidelio . Indeed, inspired by Fidelio, in 1993 I wrote an opera libretto, Erenora, recasting Beethoven’s heroine as a Maori woman.

Sixteen years later, in 2009, I began a collection of novellas called Purity of Ice. Realising that an opera production of Erenora in New Zealand was unlikely to happen, I decided to turn it into one of the novellas but giving the original libretto a preceding context: the extraordinary events of Parihaka and the exile of the prisoners of Parihaka to the South Island.

Sometimes, however, things don’t turn out the way you intend them to. The novella kept on growing as I continued my exploration of the intertextual techniques, multiple narratives and perspectives that I had begun to develop in The Trowenna Sea (2009). In this case, I was particularly fascinated about the possibilities of further acknowledging the boundaries between fiction, history and biography by making visible historical and biographical material and using footnotes. And, of course, there were the intersections with Fidelio to consider.

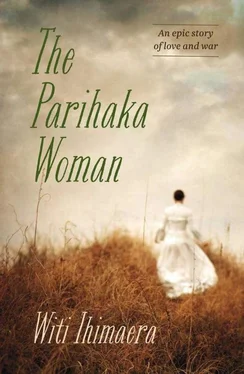

The novella was still growing when my good friend, agent and mentor, Ray Richards, to whom this book is dedicated, finally suggested that I extract Erenora from the completed collection and publish it as a separate book. It became The Parihaka Woman.

Although The Parihaka Woman is, above all else, a work of imagination, I have attempted to maintain it within an accurate historical context.

For tribal aspects and oral narrative, I am particularly grateful to Ruakere Hond (Taranaki, Ngati Ruanui me Te Ati Awa) and my friend Miriama Evans (Ngati Mutunga) who advised on the Parihaka and mana wahine aspects. Aroaro Tamati (Taranaki, Ngati Ruanui and Te Ati Awa) also read the manuscript. The main texts consulted, as far as Taranaki and Parihaka are concerned, were G.W. Rusden’s three-volume History of New Zealand, (mainly Volume 3), Chapman & Hall, 1883; and James Cowan, The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Maori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period, two volumes (mainly Volume 2), Government Printer, 1922–23. Now out of print, these texts were consulted at Wellington Central Library.

Other texts consulted from my own personal library for more specific detail were Dick Scott, Ask That Mountain, Heinemann/Southern Cross, 1975; James Belich, Paradise Reforged: A History of the New Zealanders from the 1880s to the Year 2000, Penguin, 2001; Hazel Riseborough, Days of Darkness: Taranaki 1874–1884, Penguin, 2002; Danny Keenan, Wars Without End, Penguin, 2009; Rachel Buchanan, The Parihaka Album: Lest We Forget, Huia, 2009; Kelvin Day (ed.), Contested Ground: Te Whenua i Tohea — The Taranaki Wars 1860–1881 , Huia, 2010; Michael King, The Penguin History of New Zealand, Penguin, 2003; Jane Reeves’ essay, ‘Exiled for a Cause: Maori Prisoners in Dunedin’ in Michael Reilly and Jane Thomson (eds), When the Waves Rolled In Upon Us: Essays in Nineteenth-Century Maori History by History Honours Students University of Otago 1973–93, University of Otago Press in association with History Department, University of Otago, 1999; and Bernard Gadd’s essay, ‘The Teachings of Te Whiti O Rongomai, 1831–1907’, in the Journal of the Polynesian Society, Volume 75, No. 4, 1966.

Hazel Riseborough’s text requires special mention. I agree completely with her approach, as articulated on p. 9, that ‘Archival material is a totally inadequate source from which to draw a “Maori” perspective of the Parihaka years … What he [Te Whiti] is purported to have said, and more importantly to have meant, has come to us almost exclusively through European reporters dependent on European interpreters of varying ability and persuasion.’ In her book Ms Riseborough practises what she preaches by showing admirable discipline and restraint in not offering too many instances of what Te Whiti said. When one couples this with the moving and generous offerings by Te Miringa Hohaia of waiata surrounding Te Whiti and Tohu, you realise how refined and layered Maori language is.

I also consulted some internet sites on Taranaki and on Te Whiti, Tohu Kaakahi and other real figures, notably the online Dictionary of New Zealand Biography on teara.govt.nz and the Ministry for Culture and Heritage’s NZHistory.net.nz. I apologise in advance for any omissions in acknowledging sources.

The story of Parihaka is never-ending. I look forward to the day when a son or daughter of the kainga writes with the resources available from their elders.

All errors of fact or interpretation are my own.

Special mention must be made of Te Miringa Hohaia, Gregory O’Brien and Lara Strongman (eds), Parihaka: The Art of Passive Resistance, City Gallery Wellington, Victoria University Press for Parihaka Trustees, 2001 (especially the essay by Hazel Riseborough). This publication, which was the joint winner in the history section of the 2001 Montana New Zealand Book Awards, accompanied the exhibition of the same name at the City Gallery, Wellington. Held between 26 August 2000 and 22 January 2001, the exhibition was the most significant event in recent years in terms of bringing the story of Parihaka before the public gaze.

The exhibition later travelled to other galleries, including the Dunedin Public Art Gallery, from 26 November 2002 to 10 February 2003, where a new component, Te Iwi Herehere, Nga Mau Herehere Torangapu, was added. Put together by Bill Dacker, Te Iwi Herehere conveyed the story of the Maori political prisoners from Taranaki in Otago 1869–1982. It was supported by the Dunedin Public Art Gallery and the Otago Settlers Museum and remains the most complete statement to date about the Otago prisoners.

Читать дальше