When she was an old woman in her eighties, Erenora told of the terror of the occasion in an unpublished manuscript that’s lodged in Anglican Church archives at St John’s Theological College in Auckland. As it was written in Maori, it has been overlooked and forgotten, but it is from this document that we, her descendants, have been able to access the information that is contained in this narrative.

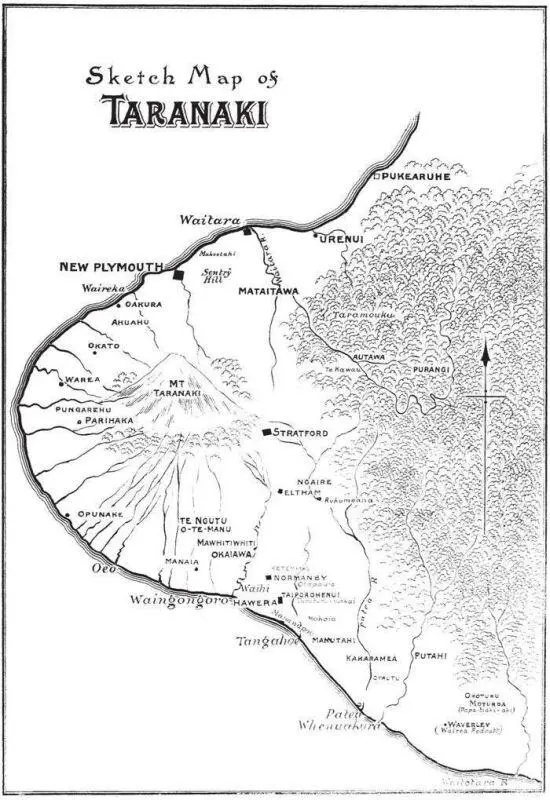

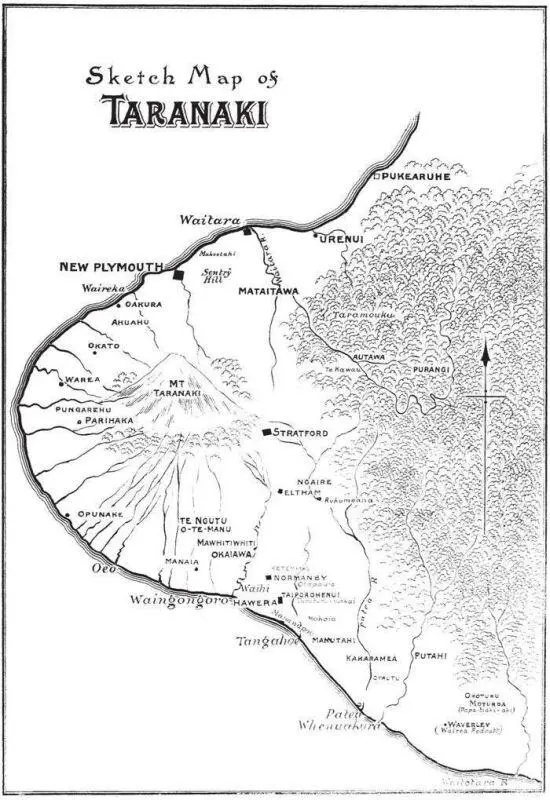

‘As well as the mission station,’ Erenora wrote, ‘Warea comprised a small group of houses with a flour mill, livestock and crop plantations; there was good trading with New Plymouth.

‘We knew, of course, that the Pakeha war with us had started. By prior arrangement, a young girl lit a huge fire at Waitara to alert all the tribes it had begun. But we had not expected Warea to be a target, so we had been carrying on our lives as normal. The deadly bombardment continued for two days, most of the shells falling short, the deafening explosions sounding all around. The Niger’s guns finally calibrated the range and pinpointed the village and, very soon, the missiles were falling on the flour mill. I was sheltering with my teachers and other children in the nearby schoolroom, aware that our situation was becoming dangerous.

‘Then the shells began to fall closer to us. I saw Te Whiti come running to the rescue. My parents, Enoka and Miriam, who had just returned from working on a nearby settler’s farm, were with him.’

Te Whiti took quick command.

‘Take the children to the pa,’ he yelled to the teachers.

Enoka told Miriam to take Erenora’s hand, and together they followed the others from the schoolroom. They were halfway across the square in front of it when, suddenly, the earth exploded beneath their feet. One minute Erenora’s parents were there, the next minute they were gone. But their bodies shielded Erenora from the blast.

Of that horrific event, Erenora had only flashes of memory: maybe she tripped, or perhaps that was when the shell which killed her parents blew her off her feet. Suddenly her mother’s hand was no longer pulling her across the compound. A voice in Erenora’s own head called, ‘Mama? Kei w’ea koe? Where are you?’

She stood up and saw two bodies on the ground; one of them was her mother’s. She ran to Miriam, shaking her, telling her to wake up. Her mother’s eyes were closed and blood was issuing from her lips and nostrils. Then Te Whiti lifted her away. He was saying something to Erenora like, ‘Your mother is dead.’ Her ears were ringing from the blast as he took her to the pa.

Erenora was frightened, in shock; she didn’t know what was happening. Nor could she understand why her parents were no longer there. Around her, in the underground chambers of the fortifications, people were praying. She couldn’t hear the words of the karakia; all she saw were the lips moving. ‘Oh God of Israel,’ the villagers prayed, ‘hear our karakia and take pity on your people in their misery. You, God of deliverance, rescue us as you did the Israelites out of Egypt.’

The Niger ’s bombardment was just the beginning of the assault on Warea. Soldiers, seamen, marines, artillerymen and others followed in an overland attack; they numbered 750 or so. Some reports say that the actual target of the shelling was the pa rather than the settlement and mission station; if so, it is puzzling that the invading force avoided the pa altogether and, although they spared the church, ransacked the rest of Warea and then retreated.

In the darkness of the pa Erenora met a young boy, about five years older, who held her tightly in his arms as the redcoat soldiers went about their business. He must have heard her whimpering at the sounds of the pillaging: rifle shots, and whooping and hollering as the village was razed.

Was it true about her mother? And father? What did being dead mean?

The young boy had tender, shining eyes and his voice was strong and comforting. ‘Don’t worry,’ he told her. ‘I’m an orphan too. Cast away your fears and don’t be sad. I will look after you.’

ACT ONE

Daughter of Parihaka

This is not a history of the Taranaki Wars. After all, I’m only a retired teacher who obtained my qualifications from Ardmore Teachers’ Training College, Auckland, in the 1960s. I will there-fore leave it to you to read the accounts of university-trained historians on the subject.

When I was younger, my elders would often talk on the marae about what happened to Maori way back then, but I really wasn’t interested. I had a well-paid job, Pakeha friends — and a Pakeha girlfriend that Josie doesn’t know about. Although I copped the occasional Maori slur or racist remark — ‘Hori’ or ‘Blacky’, you know the sort of thing — I generally laughed it off. If it got a bit too out of hand, as in, ‘Hey, you black bastard, can’t you find a girlfriend among your own kind?’ I was handy with my fists. On the whole, however, Pakeha and Maori got along pretty well really.

I think my tau’eke and kuia were affronted that I was teaching our kids about the kings and queens of England when there was all our own Maori history around us. In my own defence, I guess it was easier for me to look somewhere else, where history belonged to the victor and happened to other people, rather than locally, where we were the vanquished and it was a bloody mess. ‘Why bring up all that old stuff?’ I’d say to my elders. ‘We’re all one people now.’

It took the 1970s, when Whina Cooper led the land march from Te Hapua at the top of the North Island all the way down the spine to Parliament in Wellington, for me to confront the fact of ‘that old stuff’ and that, actually, we weren’t one people at all: history’s fatal impact had also happened here, in my own land.

I joined the march because my Auntie Rose came around to pick me up, no buts or maybes. She said to Josie, ‘I’m borrowing my nephew for a while.’

Josie answered, ‘Good, don’t return him if you don’t want to.’

The protesters carried banners proclaiming Honour the Treaty and Not One More Acre of Maori Land ; while some of the stuff they spouted was pretty offensive, there I was, right in the middle of it all, and it started to rub off on me. It wasn’t long before I looked around and realised: Hey, where was our land, here in the Taranaki? What had happened to us? My eyes were opened.

They stayed opened.

But this isn’t my story; it is Erenora’s.

I’ve done my best in telling it because, of course, Erenora wrote it originally in Maori. When the family gave me the task of translating the manuscript into English, I must say I found it daunting. A lot of her handwriting had faded, making it difficult to read. And some of her phrasing — well, I’ve had to explain it a bit for the modern reader. But I’ve tried to ensure at all times that it’s my ancestor’s voice, not mine, in the translation.

Better a family member to do the job than a stranger, eh?

‘Mine were not the only parents who were killed by the Niger ’s shells. All of us who were orphans were taken in by other families at Warea. In my case a couple by the name of Huhana and Wiremu took a shine to me. Even so, I felt I owed it to Enoka and Miriam to remember them as long as I could. As old as I am now, I have never forgotten their a’ua, their appearance. I know they loved me.

‘Following the attack, I returned to the mission’s classroom, my Bible and my books. After all, I was a little Christian girl, somewhat serious, and although I was puzzled that my parents were dead, I knew they would be together in heaven. But I did begin to wonder why, when the Pakeha professed Christian love, they would fight on Sundays, destroy the very churches we worshipped in and burn our prayer books. And why did they want to take land they did not own?

Читать дальше