All these people would follow Grandfather to the end of the earth? Why? And why did they stay?

The next morning the shearers went back to the sheds. But before leaving, Dad came to sit with us in the quarters. The others in Mahana Four were whistling for him.

‘Hey Joshua! Shake a leg!’

‘Didn’t she give it to you last night!’

It was good-natured ribaldry, but my mother’s sensitive nature made her blush.

‘Don’t listen to them, dear,’ Dad said.

He coughed. Then he took his first pay packet of the season from the shirt pocket closest to his heart. ‘He koha o taku aroha ki a koe,’ he said to Mum. ‘Please accept this gift of love.’ He put the packet halfway between them.

Trembling, our mother picked it up. ‘Tena koe mo to awhina aroha ki ahau,’ she answered. ‘I accept this gift of love.’

My mother opened the packet and divided the notes into two piles, one of which she returned to Dad. The other was the housekeeping money for the next month, and would also be used to pay off the huge debt that had accrued at the general store. By custom, Dad divided his pile in half and returned half to our mother. ‘After all,’ he said, ‘what have I got to spend it on except beer and wild women!’

With a kiss he was gone. The euphoria of having the shearers at home went with him.

Later that day I heard Grandmother Ramona talking to Grandfather about going to see Lloyd in Cook Hospital.

‘What’s the matter with you!’ she scolded. ‘Lloyd’s been in intensive care for two weeks now, and we still haven’t seen him.’

‘Every time I think of hospital I think of death. You only go to a hospital to be born or die.’

‘But we’ll only be visiting!’

‘Even so, Death’s presence is there.’

‘Oh, for goodness sake !’

Grandfather Tamihana could easily have not gone to see Lloyd. In the end, however, Grandmother Ramona taunted him about being a coward and said that she was going — and she was just a woman. So Grandfather plucked up the courage and told Mum to bring the De Soto around to the front of the homestead.

‘Simeon can come with us,’ Grandfather said. ‘He can keep an eye on the car while we are visiting. I don’t want anyone to scratch the car, Himiona.’

On the way into Gisborne, Grandfather became increasingly nervous and agitated. Grandmother tried to calm him.

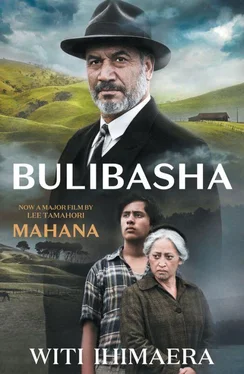

‘You’re Bulibasha after all,’ she said. ‘There’s not many people who have an angel looking after them.’

‘Ae,’ Grandfather agreed. ‘But does Death know that?’

Outside the hospital, I stood guard by Grandfather’s precious De Soto. I watched as he went with Grandmother Ramona and Mum up the stairs into the lobby. My mother was very pretty in dark suit, gloves, high heels and cloche; she was wearing a buttonhole of flowers that Glory had picked. All of a sudden she reappeared on the steps and waved to me. For a moment I thought that Grandfather had died already.

‘Himiona, haramai,’ she said. ‘They’ve moved Lloyd to a ward upstairs. You know your grandfather — he’s got that bad leg but he won’t take the lift. You’ll have to help him up the stairs.’

Grandfather still wasn’t too happy about being there, or about needing my support. As soon as we were up the stairs he pushed me away. He was sweating profusely.

‘Shall I go back to the car?’ I asked.

‘You think I’m stupid?’ he snapped. ‘You want me to fall down the stairs when I leave?’

Be my guest, I shrugged.

He motioned to me to accompany him along the shining corridor. It was almost as if he needed me to protect him. We came to a large white door.

‘Ah, you’re here to see Mr Lloyd Donovan,’ the charge nurse said. ‘Please come in. He’s expecting you.’

The door opened. Grandfather gave a loud, terrified moan. The room was silent, except for breathing. A silver barrel like a huge cream urn was in the middle of the room — but something was wrong about the urn.

A man was in it.

All I could see was his head. Then I saw a mirror slanted above the man’s head so that he could look at us. I will never forget his eyes. They widened, their irises opening out to enfold us all in his helplessness.

‘Buli-bash-aaa —’ As if only Grandfather could deliver him from the polio that had begun to cripple him. Or, failing that, give him death.

We didn’t stay long with Lloyd, but it was long enough for Grandfather to realise that Death was not after him . He calmed down and was strong and supportive to Lloyd, who was being transferred, at his parents’ request, to Waipukurau where they lived.

‘The Mahana family never forgets the people who join us,’ Grandfather said. ‘For as long as you live you will stay on the payroll. We will make sure that you have the best medical care to help you return to full health. Kia kaha.’

‘Th-ank y-ou,’ Lloyd stammered, his eyes wet with tears.

We left soon after. Grandfather, Grandmother and Mum kissed Lloyd on the forehead. Outside, Grandfather washed his hands at a tap and sprinkled himself with water. We set off back to Waituhi, and the further away we got from Cook Hospital the more Grandfather’s spirits revived. He’d come away from the House of Death unscathed.

Then, as we were going across the red suspension bridge, we saw a car coming from the other side. Oh no. Rupeni Poata’s Buick.

Mum started to slow down but Grandfather, buoyant, said, ‘Go faster, Huria. We were on the bridge first.’

Mum put her foot down. So did whoever was driving the Buick. Mum pressed the horn of the De Soto. There was an answering blare from the Buick. Mum dipped the lights: make way. The Buick’s lights dipped: you make way.

We were more than halfway across before Mum put her foot on the brakes. The De Soto skidded to a halt. So did the Buick. Just inches separated the two cars.

‘Back up!’ Caesar Poata yelled. Next to him were Tight Arse and Saul, blowing on their fists and indicating where they’d like to place them on my face.

‘ You back up!’ Mum yelled back.

‘We were on the bridge before you!’

‘Oh no you weren’t. See? We’re already over halfway, and that proves it.’

‘You maniac woman!’ Caesar yelled.

While all this was happening, Grandfather was sitting in the back seat laughing to himself. Rupeni Poata was doing the same in the back of the Buick. Grandmother was silent and still. After a moment, Grandfather got out.

‘Keep the motor running,’ he said to Mum. His manner was breezy and lighthearted.

He walked over to the Buick. Rupeni Poata got out of his car. They faced each other like Burt Lancaster and the Clayton gang in Gunfight at the OK Corral . To add to the tension, traffic was piling up on either side of the bridge. Impatient drivers were sounding their horns.

Grandfather had his walking stick. He raised it above his head and — bang . He slammed it down on the Buick’s engine cowling.

Rupeni Poata looked at the damage and shook his head sorrowfully. He had a walking stick, too. Gauging his stroke, he lifted it and — bang . He slammed it down on the De Soto’s cowling. Amused, Rupeni Poata then bowed to Grandfather and indicated that he could boot one of his headlights if he wished. Grandfather indicated that Rupeni could do the same to the De Soto.

Stalemate. The two men tipped their hats and retired.

Grandfather got back into the De Soto. He smiled at Grandmother and then, ‘Gun them down,’ he ordered Mum.

Before Caesar Poata had time to start the motor or put on the brakes, Mum had engaged the Buick’s front bumper. Rupeni Poata had just enough time to leap ignominiously into his car.

Читать дальше