So of course, nothing draws like beer, so it wasn’t long before we had company. We didn’t have many, not over four or five or six, because on a Friday afternoon nobody sticks around there that doesn’t have to. But we had that many, drinking out of the bottlenecks after Denny used the opener, and getting kind of sociable, that is, all except Morton. Morton was known simply as Salt, and when it rained he poured and at all other times he poured, a thin, do-gooder line that got on everybody’s nerves and of course only got worse with beer. However, nobody got sore at all, until after Cannon began his toasting. Who Cannon started to toast I don’t know, maybe the college or Governor Ritchie or General Pershing, it doesn’t make much difference and one guess is as good as another up to and including the Queen of Sheba. But where Salt began to look thick was on the toast to the class of 1931, that had graduated the year before. Cannon took a little trouble with it and it went something like this:

“To that noble aggregation, which beat us by one year down life’s broad highway, the class of ’31 — may they always be right, but right or left, ’31. Where, my friends, does one find such distinction, such achievement, as in the class of ’31? I pause for a reply, not knowing where to look. Is highway construction our test of solid accomplishment? This outfit has pressed more bricks than Coxey’s Army. Is it architecture? Think of the buildings that are being held up by the class of ’31. Is it philanthropy? This outfit has panhandled more dimes than John D. Rockefeller would be able to give away the whole coming year. Is it agriculture? Think of the apples ’31 has peddled in the streets, and only a year out of school yet. Is it tonsoriology? A blind man could shave himself by the shine on the seat of these bastards’ pants. Is it—”

“I don’t care for that.”

“Salt, what have I said to offend you?”

“It’s not what you say. It’s how you say it.”

“You mean my deep, mellifluous voice?”

“I mean your scoffing tone.”

“Are you by any chance taking up for these sons of bitches that showed not the least fraction of a human soul when we got here four years ago, that razzed us and taunted us and hazed us, that—”

“I don’t take up for ’31 at all. To hell with them! But if they want work, there’s still work to do—”

“Oh, yeah? Pray tell us.”

Then Cannon asked Salt what he was going to do when he got his dip. He said he was going with the Consolidated Engineering Company, but it was quite well known that Consol was owned by his uncle, and had contracts all over, specially wherever the government needed dredges. That got him the raspberry, and Cannon went on: “Here’s to Admiral Byrd!”

“Ray!”

“Babe Ruth!”

“Ray!”

“Jean Harlow!”

“Oh, boy!”

“President Hoover!”

“Hip, hip—”

“Morituri, te salutamus!”

But Salt had stood up when Mr. Hoover’s name was mentioned, and that was when Denny swung. There was quite a roughhouse, and I guess it was five or six o’clock when I got it quieted down and all of them thrown out. But along around ten, when the beer had worn off and we’d had something to eat, I lay down and kept thinking about it. “Denny, what was that he said? That sounded like Latin.”

“May be in the dictionary.”

I thought I remembered the first word of it, and sure enough after a while I found it. “Denny, you know what it means?”

“Not noticeably.”

“‘We who are about to die salute you.’”

“Well?”

“Is that how he feels?”

“Why not? He’s on the end of the plank.”

“Is that how you feel, Denny?”

“... I don’t know.”

“What are you going to do when we graduate, Denny?”

“Point of Rocks.”

Point of Rocks is a place on the Potomac, thirty or forty miles up from the District on the Maryland side, where Mr. Deets had a little farm, but he used it mainly when he felt like fishing. That Denny would hole up there just gave you an idea how far things had gone in the way of jobs. Of course there hadn’t been much out of him about pro football since I cracked my knee. It turned out in a professional game if he didn’t have me to take him through the line he wasn’t going through the line, so after getting the liver, lights, and gizzard knocked out of him a couple of times he didn’t get called any more. “You really going to Point of Rocks?”

“Well, where the hell would I go?”

If it was the beer wearing off, or he’d been worrying, I don’t know, but he was disagreeable and sounded bitter. That was when I got it through my head at last: if it could take the starch out of Denny, it was bad. So that’s why I talked like I did to Mr. Legg. That wasn’t a nice kid talking to a nice father about a nice girl. It was a guy that was losing his nerve making the best of things he could.

All that time, not only after the New Year’s party but before it, when I’d be booked to appear with Margaret or tagged for one of her parties or seeing her for one reason or another, little Helen was growing up. When Margaret and I first began doing shows together she was around two and couldn’t talk yet. Just the same she knew me whenever I came, and I’d have to stand there and listen to her tell me all about it or anyway think she was telling me, and a little later, at the parties, I’d stuff her full of ice cream and the more I saw of her the more wonderful she thought I was and the more wonderful I thought she was. She was just a little tyke, with blue eyes and yellow hair, but I had never run into anything like her, for prettiness and friendliness and the smile that lit her up like a Christmas tree. When she was a little older we’d go out together, to the drugstore for a soda or wherever it would be, and we didn’t exactly walk, but we did a pretty good sashay: her in front, dancing along backwards, me coming along behind, with a doll in my arms or one of the puppies on a leash or the stroller, so I could push her if she got tired. A little later we’d go to the picture show. Then a little after that, when I was in college and she was in the Sarah Read School around the corner, she’d see my picture in the paper and call me up after the games and want to know why I hadn’t sent her tickets. I’d say she was a little young yet. It wasn’t until after the New Year’s party that I began coaching her in arithmetic. She was just naturally dumb at it, and there was some talk about it at dinner one night. Her father kept saying, “It’s all right, we’ll get a tutor,” but Mrs. Legg was pretty disagreeable about it that Helen didn’t study the subject, as she said. Then she got off a lot about the honors she had taken when she was a young girl at school, and you kind of got the idea she was sore because Helen wasn’t a credit to her. I kept thinking how easy everything, the music at least, had been for me at that age when Miss Eleanor made a game out of it, and then I heard myself say: “Mrs. Legg, why can’t I be her tutor?”

“You, Jack?”

“At least I know my math.”

“Whoo!”

Margaret exploded like it was the funniest thing she ever heard in her life, and Mrs. Legg was crossed up because she wasn’t in favor of a tutor. But Mr. Legg jumped at it. I don’t know why, but my guess is that even at that time he had his eye on me, on account of Margaret’s career bug, and this was just one more knot he could tie in my tether. The upshot was she was to come up to the house Saturday mornings, and I was even to get paid for it. I squawked at that, said I’d be glad to do it for nothing, but he was set that I had to get something, so we made it five dollars for two hours, ten to twelve.

Читать дальше

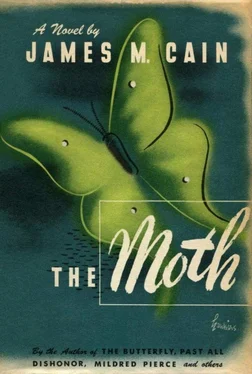

![Джеймс Кейн - Почтальон всегда звонит дважды [сборник litres]](/books/412339/dzhejms-kejn-pochtalon-vsegda-zvonit-dvazhdy-sborni-thumb.webp)