“Come on, let’s have it.”

“Some I carried for you on margin.”

“And—?”

“It’s gone.”

“Well, what does the totalizer say?”

“I have the list here... It says, at the prices I paid for it, there’s three thousand dollars odd of stock in the clear, and two small government bonds. What any of that is worth now I’d hate to say. It could be sold, I guess. Whether dividends will continue, that we don’t know. But, disregarding the future, considering only now — it’s gone.”

“Everything?”

“Practically.”

“Well, that’s that.”

“Jack, it tortures me, it humiliates me, it — stultifies me, that I have to tell you this, after the issue I made of it. I’d give my right hand not to, for I think you’ll believe me when I say if I could draw the money from the bank and hand over what I lost for you, I’d do it. I can’t. I haven’t told you everything. There’s more. I myself am heavily hit. I said nothing to you, but I’ve expanded. With your friend Denny’s father, I leased a lot, on Mt. Royal near the Automobile Club, and started a big garage, with general service, pit for car wash, pumps, tanks, jacks — an installation in six figures. We were unequal to it alone, naturally, and went to a bank. And since this they’re pressing us hard. And while we’ve raised something — how I simply won’t tell you — we’re still in frightful shape. The big service station is completely gone as a possibility at this time. The agency, the North Avenue place, I keep, but it’s — involved. Heavily. All I can say is, when I can, if I ever can, I shall regard your funds as a debt, and you shall—”

“Look, everybody makes mistakes.”

“—be paid. Now, as to college—”

“I have a deal. If I want it, there’ll be a job.”

“What kind of a job?”

“I don’t know. They’ve got ethics now, though, whatever they are, and I can’t just play football.”

“But you can finish?”

“Oh, sure.”

“Thank God for that.”

“Don’t worry about me.”

“Sam Shreve shot himself, if that helps.”

“I’m sorry to hear it.”

“He — gave us the benefit of his best judgment, but it wasn’t good enough, let us say.”

“That often happens.”

I went back to my room, lay down again, and thought of what she had said, about checking up on my stock. That seemed about all it amounted to: one more thing to remind me of her. As to being broke, that didn’t seem to mean anything, and as for his losing my money for me, I didn’t hold it against him. But it seemed funny to me, from the brush-off I gave it, that he wouldn’t know there was something on my mind, and at least ask me what it was. Well, why couldn’t I tell him what it was? If I knew that, I wouldn’t be writing all this up.

Almost at once, from a house where things were done in a freehanded way, it turned into a house that needed money, where everybody drew deep breaths, let them out trembly, and went whole days without looking at each other. It was the same up and down the street, all you heard at the drugstore on North Avenue, or anywhere. Denny felt it, and it was the first time I found out what his father did, besides going to Europe all the time. He was an investor. He had inherited property from his father, a cement works somewhere near Catoctin Mountain, where Lee and McClellan tangled just before Antietam, and then branched out into contracting, road-building, bridge-building, and stuff like that. But he let the superintendent attend to construction, and concentrated on backing businesses, or buying into them, or foreclosing on them, as some said, and taking his profit on those that panned out. So that was how he and the Old Man came to be mixed up in the Mt. Royal Avenue thing. Mt. Royal Avenue, in Baltimore, is a continuation of Mt. Royal Terrace and the same street they’ve got in every big city, the center of the automobile trade. The Old Man was a little ahead of his day, but he saw the need for what is now called super-service, with every kind of work done on the spot and none of it sent out, and trouble-shooting on a twenty-four-hour schedule. That kind of location cost money, the equipment cost money, and the stock cost money. But Mr. Deets got hit too, because he was one hundred per cent in the market, with no sidelines for a cushion if something went wrong. One day he was rich, the next day he was a bum, or as near it as a guy like that, with forty-seven connections, ever really gets. Denny took it hard, and that I could have stood, but he also took it big. I mean, he’d drop around, and we’d take a ride, because at least I had the Buick that followed the Chevvie. Then he’d talk about what we were going to do about it. I didn’t know, and I was still mooning about what happened in Easton. And then one day, just after Thanksgiving, when we’d gone back to college, he came in the room and closed the door in his same old hush-hush way. “Jack, I’ve been in town.”

“Baltimore?”

“Washington. The Willard. And I ran into the gang from Fall River.”

He didn’t say Fall River. He said a city not far from Fall River, but I’ve got my reasons for not naming it. “... What do you mean, Denny, you ran into them?”

“Maybe on purpose.”

“But not any good purpose, naturally.”

“Listen, Jack, they need players.”

“Why?”

“They had a row. Over a bonus that was supposed to be paid, or that some of them said was supposed to be paid, after their last game. And it wasn’t paid. And the backfield quit.”

“Sounds like a nice outfit.”

“I said they need men.”

“Stop feinting and jabbing around—”

“We could change our names, Jack.”

“And our faces?”

“That’s not so hard... O.K., I talked to the manager and tonight I’m to call. They’re due in New York, the Polo Grounds, Sunday, and I think it’s ours if we want it, fifty bucks and our fare apiece, and me, I’m in. I need fifty bucks.”

“I’m listening, stupid.”

So from then on, on Sundays, I played as a pro. Denny called himself Rex Atlas, but I settled for Jake Healy. We gave out that we were Washington “sand lotters,” whatever that meant, but it seemed to get by. Denny worked on my brows with some kind of dye he got, so they’d be brown, instead of yellow. For the pictures, whenever they were taken, he made little pinches of cotton, that we carried up the sleeve of our jerseys, and would stick in our mouths, between the gum and the lip, upper and lower, and it certainly gave us a queer, buck-toothed look all right. Looking back at it now it seems funny. It didn’t then. I felt ashamed, and if we were caught I didn’t know what I’d say to Byrd. From then on I was doing all kinds of things I couldn’t look myself in the eye over. I wasn’t a cocky, tingle-fingered kid any more. I was a guy with muscles for rent, that took no pride in what he did with them, and wanted to talk about something else whenever the subject came up.

It was in the Christmas holidays that Margaret called, and asked me to a party at the hotel New Year’s Eve. I said I’d come if I could, as it was still heavy on my mind about Easton, and I wasn’t much in the humor. But then, the morning of the party, it came out in the Sun, under an Easton date line, about the marriage, and it turned out she was even more prominent than she had said, because it was on the society page, and got some space. So I thought to myself: My young friend, you’re going to the party. So I put on the black tie the Old Man had given me the previous Christmas, and went. I was surprised at the change in her, as I hadn’t seen her in some months. She had slimmed quite a lot, so she wasn’t so corn-fed and had a figure. And her face had lost the blobbiness it had had, so it was reasonably good-looking. She had on a pink dress that went nice with her dark hair, so I shook hands and admired the new shape, and she didn’t seem to mind that kind of talk at all. When the music started I asked her to dance. Denny was there, and he’d got a load of the reconditioned shape, so while the fiddlers were tuning he whispered that by God, he was going to do something about that. But who she danced off with was me.

Читать дальше

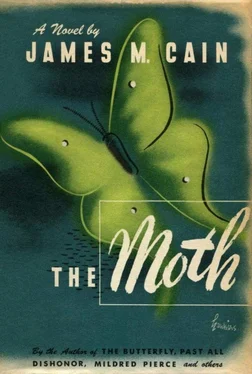

![Джеймс Кейн - Почтальон всегда звонит дважды [сборник litres]](/books/412339/dzhejms-kejn-pochtalon-vsegda-zvonit-dvazhdy-sborni-thumb.webp)