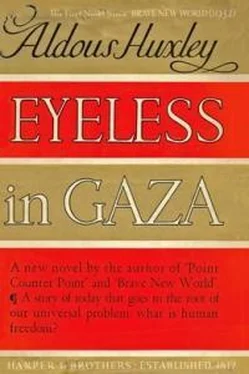

Олдос Хаксли - Eyeless in Gaza

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Олдос Хаксли - Eyeless in Gaza» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2019, Издательство: epubBooks Classics, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Eyeless in Gaza

- Автор:

- Издательство:epubBooks Classics

- Жанр:

- Год:2019

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Eyeless in Gaza: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Eyeless in Gaza»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Eyeless in Gaza — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Eyeless in Gaza», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

No, said old Mrs Benson, Mr Foxe hadn’t yet come back.

He had his tea alone, then sat on a deck–chair on the lawn and read de Gourmont on style. At six, Mrs Benson came out, and after elaborately explaining that she had the table and that the cold mutton was in the larder, wished him good evening and walked away down the road towards her own cottage.

Soon afterwards the midges began to bite and he went indoors. The little bird in the Swiss clock opened its door, cuckooed seven times and retired again into silence. Anthony continued to read about style. Half an hour later the bird popped out for a single cry. It was supper–time. Anthony rose and walked to the back door. Behind the cottage the hill was bright with an almost supernatural radiance. There was no sign of Brian. He returned to the sitting–room, and for a change read some Santayana. The cuckoo uttered eight shrill hiccups. Above the orange stain of sunset the evening planet was already visible. He lit the lamp and drew the curtains. Then, sitting down again, he tried to go on reading Santayana; but those carefully smoothed pebbles of wisdom rolled over the surface of his mind without making the smallest impression. He shut the book at last. The cuckoo announced that it was half past eight.

An accident, he was wondering, could the fellow have had an accident? But, after all, people don’t have accidents—not when they’re out for a quiet walk. A new thought suddenly came to him, and at once the very possibility of twisted ankles or broken legs disappeared. That walk—he felt completely certain of it now—had been to the station. Brian was in the train, on his way to London, on his way to Joan. It was obvious when one came to think of it; it simply couldn’t be otherwise.

‘Christ!’ Anthony said aloud in the solitude of the little room. Then, made cynical and indifferent by the very hopelessness of the situation, he shrugged his shoulders and, lighting a candle, went out to the larder to fetch the cold mutton.

This time, he decided, as he ate his meal, he really would escape. Just bolt into hiding till things looked better. He felt no compunction. Brian’s journey to London had relieved him, in his own estimation, of any further responsibility in the matter; he felt that he was now free to do whatever suited him best.

In preparation for his flight, he went upstairs after supper and began to pack his bag. The recollection that he had lent Brian The Wife of Sir Isaac Harman to read in bed sent him, candle in hand, across the landing. On the chest of drawers in Brian’s room three envelopes stood conspicuously propped against the wall. Two, he could see from the doorway, were stamped, the other was unstamped. He crossed the room to look at them more closely. The unstamped envelope was addressed to himself, the others to Mrs Foxe and Joan respectively. He set down the candle, took the envelope addressed to himself, and tore it open. A vague but intense apprehension had filled his mind, a fear of something unknown, something he dared not know. He stood there for a long time holding the open envelope in his hand and listening to the heavy pulse of his own blood. Then, coming at last to a decision, he extricated the folded sheets. There were two of them, one in Brian’s writing, the other in Joan’s. Across the top of Joan’s letter Brian had written: ‘Read this for yourself.’ He read:

DEAREST BRIAN,—By this time Anthony will have told you what has happened. And, you know, it did just happen—from outside, if you see what I mean, like an accident, like being run into by a train. I certainly hadn’t thought about it before, and I don’t think Anthony had—not really; the discovery that we loved one another just ran into us, ran over us. There wasn’t any question of us doing it on purpose. That’s why I don’t feel guilty. Sorry, yes—more than words can say—for the pain I know I shall give you. Ready to do all I can to make it less. Asking forgiveness for hurting you. But not feeling guilty , not feeling I’ve treated you dishonourably. I should only feel that if I had done it deliberately; but I didn’t. I tell you, it just happened to me—to us both. Brian dear, I’m unspeakably sorry to be hurting you. You of all people. If it were a matter of doing it with intention, I couldn’t do it. No more than you could hurt me intentionally. But this thing has just happened, in the same way as it just happened that you hurt me because of that fear that you’ve always had of love. You didn’t want to hurt me, but you did; you couldn’t help it. The impulse that made you hurt me ran into you, ran over you, like this impulse of love that has run into me and Anthony. I don’t think it’s anybody’s fault, Brian. We had bad luck. Everything ought to have been so good and beautiful. And then things happened to us—to you first, so that you had to hurt me; then to me. Later on, perhaps, we can still be friends. I hope so. That’s why I’m not saying good–bye to you, Brian dear. Whatever happens, I am always your loving friend,

JOAN.

In the effort to keep up his self–esteem and allay his profound disquietude, Anthony forced himself to think with distaste of the really sickening style in which this kind of letter was generally written. A branch of pulpit oratory, he concluded, and tried to smile to himself. But it was no good. His face refused to do what he asked of it. He dropped Joan’s letter and reluctantly picked up the other sheet in Brian’s handwriting.

DEAR A.,—I enclose the letter I received this morning from Joan. Read it; it will save me explaining. How could he have done it? That’s the question I’ve been asking myself all the morning; and now I put it to you. How could you? Circumstances may have run over her—like a train, as she says. And that, I know, was my fault. But they couldn’t have run over you. You’ve told me enough about yourself and Mary Amberley to make it quite clear that there could be no question in your case of poor Joan’s train. Why did you do it? And why did you come here and behave as though nothing had happened? How could you sit there and let me talk about my difficulties with Joan and pretend to be sympathetic, when a couple of evenings before you had been giving her the kisses I wasn’t able to give? God knows, I’ve done all manner of bad and stupid things in the course of my life, told all manner of lies; but I honestly don’t think I could have done what you have done. I didn’t think anybody could have done it. I suppose I’ve been living in a sort of fool’s paradise all these years, thinking the world was a place where this sort of thing simply couldn’t happen. A year ago I might have known how to deal with the discovery that it can happen. Not now. I know that, if I tried, I should just break down into some kind of madness. This last year has strained me more than I knew. I realize now that I’m all broken to pieces inside, and that I’ve been holding myself together by a continuous effort of will. It’s as if a broken statue somehow contrived to hold itself together. And now this has finished it. I can’t hold any more. I know if I were to see you now—and it’s not because I feel that you’ve done something you shouldn’t have done; it would be the same with anyone, even my mother—yes, if I were to see anyone who had ever meant anything to me, I should just break down and fall to bits. A statue at one moment, and the next a heap of dust and shapeless fragments. I can’t face it. Perhaps I ought to; but I simply can’t. I was angry with you when I began to write this letter, I hated you; but now I find I don’t hate you any longer. God bless you,

B.

Anthony put the two letters and the torn envelope in his pocket, and, picking up the two stamped envelopes and the candle, made his way downstairs to the sitting–room. Half an hour later, he went to the kitchen, and in the range, which was still smouldering, set fire one by one to all the papers that Brian had left behind him. The two unopened envelopes with their closely folded contents burnt slowly, had to be constantly relighted; but at last it was done. With the poker he broke the charred paper into dust, stirred up the fire to a last flame and drew the round cover back into place. Then he walked out into the garden and down the steps to the road. On the way to the village it suddenly struck him that he would never be able to see Mary again. She would question him, she would worm the truth out of him, and having wormed it out, would proclaim it to the world. Besides, would he even want to see her again now that Brian had … He could not bring himself to say the words even to himself. ‘Christ!’ he said aloud. At the entrance to the village he halted for a few moments to mink what he should say when he knocked up the policeman. ‘My friend’s lost … My friend has been out all day and … I’m worried about my friend … ’ Anything would do; he hurried on, only anxious to get it over.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Eyeless in Gaza»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Eyeless in Gaza» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Eyeless in Gaza» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Олдос Хаксли - О дивный новый мир [Прекрасный новый мир]](/books/11834/oldos-haksli-o-divnyj-novyj-mir-prekrasnyj-novyj-thumb.webp)