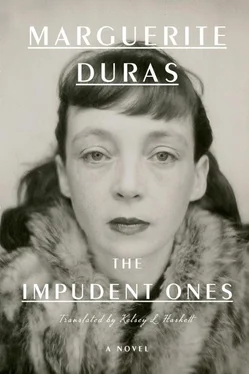

The settings of Les impudents , a residential suburb of the French capital and a village in the southwestern part of the country, are versions, under altered names, of places where the author lived when she came back to France as a child and then again for a few weeks as an adolescent in 1931. In the opening chapter, the apartment occupied by the Grant-Taneran family, the septième from which Maud contemplates a landscape extending to “the somber streak of the hills of Sèvres,” appears to be the very same seventh-floor apartment her mother rented in 1931 in a new art-deco building still standing today in its gleaming whiteness at 16, avenue Victor-Hugo, in Vanves, west of Paris. In the novel, walking through the streets of Clamart (Vanves), she can see from a distance “the huge white hulk of the building in which they lived.” Taking us on a tour of the apartment, the narrator takes care to point out the Henri II sideboard in their dining room (for many French readers, a sure sign of petitbourgeois taste), lest we think of the family as fashion-minded sophisticates.

A Bourgeois Drama

Mrs. Grant-Taneran may be a petit-bourgeois who cooks her own meals (by contrast, in 1931, Mrs. Donnadieu brought her cook with her to Paris from Indochina), but the mother in The Impudent Ones owns land in the southwest, an estate she presumably acquired with the savings of her first husband, a tax collector (like the author’s father-in-law). With some major changes in the chronology and the nature of the autobiographical events that inspired it, the story unfolds around that prized Uderan estate, “located in the southwest Lot, in the rough and unpopulated part of Upper Quercy, on the edge of Dordogne and Lot-et-Garonne.”

With some minor geographical realignments, one can easily make the short trip on a map to the estate Marguerite Duras’s father bought a few weeks before he died unexpectedly in France in 1921, at age forty-nine, during a medical leave of absence. This is the rural environment where, between the ages of eight and ten, his daughter spent two years with her mother and her two brothers, and which the author would evoke in vivid detail in The Impudent Ones. Le domaine de Platier (its real name) originally comprised forty-five acres of woods, vineyards, orchards, meadows, and a tobacco plantation, situated near the small village of Pardaillan (The Pardal in the novel), a few kilometers east of the historical hill-town of Duras (Ostel in the novel)—the town from which Marguerite later took her nom de plume.

When Marguerite Duras returned to France with her mother and her brother Paul in the spring of 1931 (Pierre was by then living in Paris), the maison de maître in which they had previously lived had been emptied of its furniture and unoccupied for several years. {6} 6 Henri Donnadieu died without leaving a will. The Platier estate became embroiled in a lengthy legal action initiated by his brother, intent on ensuring the rights of Marguerite Duras’s half brothers. In 1924, before going back to Indochina, Marie Donnadieu was able to buy back the property, but the main house had to be emptied of all its contents, which were sold at public auction. When they came back in 1931, the house had been sealed off for several years.

As it was now unhabitable, they had to take board and lodgings with neighbors for a few weeks while Marie Donnadieu organized the sale of the estate, which included an old farmhouse in the back of the main dwelling that housed a sharecropping couple and their daughter, still tending the land for the absentee owner.

These characters are all made to play a part in The Impudent Ones —the neighbors as the Pecresse family, the tenant farmers as the Dedde family. The Pecresses would not mind marrying their son to their guest’s daughter (thus acquiring a stake in the estate), but they are kept firmly in their assigned rank on the social ladder. The narrator takes pains to explain: “Even if the Grant-Tanerans were only bourgeois folk without distinction, Uderan, their land, conferred on them a kind of nobility.” Thus, while Maud is addressed as Mademoiselle Grant , or “la Demoiselle” and her mother as Madame , or Madame Grant-Taneran , the neighbors by contrast are referred to by the less respectful La Pécresse, la mère Pécresse, Le Pére Pécresse, le jeune Pécresse; and the tenant farmers as La Dedde, le père Dedde, la fille Dedde —the way people in the countryside called each other at the time.

Many of the inhabitants of Pardaillan figure in the novel as extras, vividly rendered through the author’s observant eye and ear for popular parlance (“in the thick dialect of the Dordogne”). Lording over the locals, Mrs. Grant-Taneran gives a grand diner for the villagers in her dilapidated mansion. The guests are seated according to rank, and what ensues is a small comedy of manners in the spirit of Gustave Flaubert or Guy de Maupassant.

In another parallel to the author’s life, the reader is informed at the beginning of the story that “Jacques had just lost his wife… She had died that very day following a car accident.” In real life, before his mother and siblings arrived in France in 1931, Pierre Donnadieu, then nearing twenty-one, had been living in Paris with a wealthy woman who died in a car accident—a possible suicide.

The lover that Maud takes up when the family relocates to their summer estate appears to be modeled on Jean Lagrolet, the handsome scion of an upper-middle-class family, whom Marguerite Duras met at the Sorbonne and dated for two years in the 1930s. The public scandal at the heart of the novel, loss of prestige for Maud’s family, and secret pregnancy that ultimately shatters the clan also seem to have been inspired by real-life events. In 1932, at the age of eighteen, Marguerite Duras was dating one of her schoolmates from the private establishment she was attending—the son of a prominent family of lawyers—and became pregnant. Contrary to the loveless but conventional ending in the novel, however, no wedding was celebrated. A discreet abortion was arranged, which the author would reveal much later in her career. {7} 7 In 1971, Marguerite Duras joined a group of prominent women who signed a petition calling for the French law criminalizing abortion to be repealed. Simone de Beauvoir (who wrote the petition), Françoise Sagan, Catherine Deneuve, and Ariane Mnouchkine were among the one hundred and twenty-three women who revealed publicly that they had had an abortion.

Literary Influences

In his assessment of the novel for Gallimard, Marcel Arland wrote: “It is very awkward, rather badly put together, confused… rudimentary, sometimes incoherent—but there is here a rather strange atmosphere (à la Mauriac and Wuthering Heights ), a certain grasp of family turmoil, of cruelty, of moral degradation.” {8} 8 Gallimard archives.

That Marguerite Duras was influenced by François Mauriac there is little doubt. She was an avid reader, fully cognizant of the prevailing trends in French fiction between the two wars. While studying law at the Sorbonne, she audited public classes on contemporary literature given by Fortunat Strowski, an eminent specialist who coincidentally had been Mauriac’s teacher at the University of Bordeaux before World War I. At the time she was writing The Impudent Ones , Mauriac had become one of the most eminent French novelists (he was elected to the prestigious Académie française in 1933). His stories of divided and secretive provincial families from the grande bourgeoisie , such as Thérèse Desqueyroux , published in 1927, and Le noeud de vipères , published in 1932, inspired legions of aspiring writers at odds with their bourgeois environment. Mauriac himself was an admirer of Paul Bourget, the late nineteenth-century author of celebrated romans psychologiques set in upper-middle-class families, including a series of novels purporting to analyze “women’s emotions.” (Bourget was supposedly Henry James’s favorite French writer.)

Читать дальше