The problems of lucidity and cohesiveness, first recognized by the two French presses that dealt with the novel, still present a challenge to the reader and the translator today, not only in regard to the plot, which at times lacks clarity, but also in relation to the interplay between characters. Unclear antecedents for pronouns and oblique grammatical constructions are among the stylistic challenges that often make it difficult to determine precisely who is speaking or the intended meaning of a given phrase or sentence. To overcome these ambiguities and facilitate a greater enjoyment of the text, the goal of the present translation has been to render the reading of the novel as intelligible as possible for the reader. This has been accomplished through the addition of occasional words and phrases, not in the original, to provide smoother transitions as the text unfolds, and by the replacement of pronouns by proper nouns in dialogues and interactions that are less than clear. In every case, adherence to the original meaning of the text has been of utmost concern.

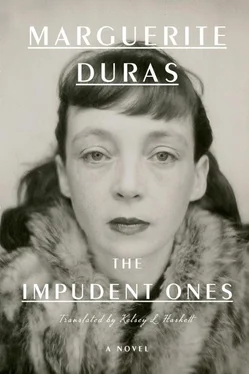

In recent years, The Impudent Ones has taken on new meaning for readers and scholars around the world, as it has come to be appreciated not only for its significance to the rest of Duras’s work, but increasingly for its intrinsic value as a novel. Although already translated into a number of other languages, this first translation of the novel into English, some seventy-eight years after its original publication, will now allow the novel to be accessed by a much broader readership. In doing so, it will reveal to a new public the starting point of the exceptional qualities of observation and description that characterize Duras’s celebrated later works, while affording a view of the renowned author as she first gains a foothold in the world of writing. Of no less consequence, The Impudent Ones also provides a record of a time, place, and personal connection that were undeniably of great significance to Marguerite Duras, not only as she began her career, but throughout her life.

THE STORY BEHIND THE IMPUDENT ONES

JEAN VALLIER

In February 1941, Gaston Gallimard, the founder and owner of the famed French publishing house that bore his name, received a manuscript in the mail, accompanied by the following letter:

Monsieur,

My name is perhaps not totally unknown to you, because I co-authored the book The French Empire , published by your house last year. But the manuscript I am submitting to you today— La famille Taneran —has no connection to this first book, which was for me but a work for hire. I now wish to make my debut as a novelist. The manuscript I am sending you was read by Messrs. Henri Clouard, André Thérive and Pierre Lafue, who liked it very much and strongly encouraged me to have it published. I trust their opinion. I hope that it will correspond to yours. I should be glad in any case to receive your answer without too much delay.

Yours faithfully, Marguerite Donnadieu

{1} 1 Gallimard archives.

This letter, addressed to the publisher of literary giants such as Proust, Gide, and Paul Valéry, was not written by a timorous would-be novelist. Apart from the fact that her name had appeared the year before on the cover of L’empire français , she had reason to believe that the names of the three gentlemen who vouched for the quality of her manuscript would not fail to impress her correspondent: Henri Clouard and André Thérive were at the time two of France’s most influential literary critics, and Pierre Lafue, a novelist and a respected critic himself, was a governmental agent who had played a part in the publication of her first book and was now one of her most devoted friends. She knew he had privileged access to Gaston Gallimard.

Contrary to the legend of poverty and abuse still hanging over the story of her early life, when the future Marguerite Duras wrote her first novel—thanks in great part to the college education her mother enabled her to receive—the young writer had grown into a secure, self-assured young woman. {2} 2 The legend that Marguerite Duras created herself—that she grew up extremely poor and suffered at the hands of a dominating and indifferent mother and an abusive older brother—rests mostly on two of her books, The Sea Wall and Wartime Writings . Inspired by real-life family events, these are nevertheless mostly fictional accounts. Duras’s Wartime Writings , which include ostensible reminiscences about her youth, are not actual diaries and need to be analyzed carefully in order to separate fact from fiction.

Now twenty-six and married, she had joined the Parisian bourgeoisie and was not easily daunted—a side of her nature she would continue to display for the rest of her life.

Born near Saigon in 1914, Marguerite Donnadieu was the daughter of two teachers who worked in the educational system put in place by the French in Indochina, a colony comprised of what is now Vietnam, as well as Cambodia and Laos. Her father, Henri Donnadieu, born in southwestern France in 1872, held a university degree in natural sciences, which he taught occasionally in Saigon and Hanoi between assignments as a school director and education supervisor. Her mother, born Marie Legrand in the Pas-de-Calais in 1877, trained at a teacher’s college in Lille before going to Indochina in 1905, where she taught and was ultimately placed in charge of several establishments for Vietnamese girls. When they met, Henri had two sons from a previous marriage who returned to France after their mother died. He married Marie Legrand in Saigon in 1908 and had two sons with her before Marguerite’s birth: Pierre, her frère aîné , in 1910, and Paul, her petit frère , in 1911.

The three children traveled to France several times, first with both parents during World War I when Marguerite was still a toddler, then with their widowed mother, following the premature death of their father to malaria in December 1921. The family remained in France between 1922 and 1924. They lived in a small village in the Lot-et-Garonne, east of Bordeaux, in a house Henri Donnadieu had bought near the place of his birth, presumably for his retirement. Marie Don-nadieu having decided to return to Indochina to resume her career, they left for Saigon in the summer of 1924. After seven years in the Mekong Delta where their mother had been posted, in 1931, Marguerite and her brother Paul returned with her to France for one year (Pierre, the eldest, had been sent back to France in 1924 to study). They lived on the outskirts of Paris, where Marguerite attended a private school in the sixteenth arrondissement and passed the first part of her baccalauréat . Back in Saigon, she completed her secondary studies at the city’s lycée in 1933. In the fall, she left Indochina for the last time, returning to Paris to further her education. She attended law school at the Sorbonne for four years, graduating in 1937 with a degree in common law and political economics. In June of that year, she was hired by the French Ministry of the Colonies to write promotional materials. At twenty-three, she was now independent financially and free to live as she pleased. She was making a good salary, could afford nice clothes, and drove her own Ford coupé convertible, which she used to explore the countryside or go to the seashore with her beau of the moment.

L’empire français

Georges Mandel, a major figure in the history of the Third Republic, was appointed Minister of the Colonies in 1938, and brought with him Pierre Lafue, his speechwriter. Mandel was determined to use his position to counter Germany’s war propaganda, issuing a continuous stream of interventions in the press, on the state-controlled radio network, and in weekly newsreels shown in movie theaters. In 1939, in order to publicize the part that French overseas possessions could play in the looming conflict in terms of foot soldiers and war materiel, he asked his staff to put together a book about the country’s colonial empire. His press attaché, a young man named Philippe Roques, took up that task with the help of the Indochina-born Mademoiselle Donnadieu, whose own pen had caught the attention of her superiors. Her name ultimately appeared on the book’s cover, next to the name of her colleague. Gallimard agreed to publish the book based on an advance order from the ministry for three thousand copies, to be given out at the Salon de la France d’Outremer planned to be held in Paris the following year.

Читать дальше