That September, the Nazis invaded Poland. Despite the war, the “Overseas France” salon opened on schedule on May 6, 1940, with Albert Lebrun, the president of the French Republic, and Georges Mandel, the Minister of the Colonies, in attendance. At the salon’s entrance, fresh off the printing press, L’empire français was offered to visitors. The co-authors would not enjoy their nascent notoriety for long, however. Four days later, Hitler’s armies, bypassing the “unassailable” Maginot Line in the East, invaded France from Belgium. Within weeks, as German tanks continued their progression from the north, Paris was declared an open city to avoid its destruction. All the French ministries had to leave town.

Marguerite Duras left the French capital with Lafue and Roques on June 9, first for the Loire Valley, where the ministries took temporary refuge, then for Bordeaux five days later, where the French government withdrew as the soldiers of the Third Reich marched down the Champs-Élysées. At the end of the month, after fighting had stopped (the armistice was signed on June 22), she left Bordeaux with Lafue and went with him to Brive-la-Gaillarde, a small city near the Dordogne where Lafue’s brother and his family lived. After a few weeks in Brive, she returned to Paris in mid-August. (Philippe Roques joined the Résistance movement and went on to serve as a secret agent between de Gaulle and Mandel, as well as between Churchill and Mandel, until he was captured and killed by the Gestapo in 1943.)

A Married Woman Under Vichy

Much had changed since she left the French capital. A new government had been born from the defeat of the French army, with la République française ceding control to the authoritarian l’État français, led by Marshal Philippe Pétain, a hero of World War I who was recalled from his ambassadorial post in Madrid. Not given to progressive thoughts, the eighty-year-old Pétain, under the pretext of sparing the French further miseries, was soon advocating cooperation with the invaders and taking a series of repressive measures in order to rid France of its “past errors.” “Liberté, égalité, fraternité” was now replaced by “Travail, famille, patrie (Work, family, fatherland),” a motto more in tune with the return to ancestral values preached by the old marshal and his entourage. From now on women were expected to stay home. Unless they were under permanent contract with the state (such as teachers in public schools), married women would no longer be authorized to work in the French administration.

Marguerite Duras’s position as an auxiliary with the Ministry of the Colonies was about to be terminated. Newly unemployed, she would have to depend on her husband’s salary, a situation that circumstances related to the war had made problematic. In September 1939, a few weeks after the hostilities started, she had married Robert Antelme, the son of a tax officer in the affluent sixth arrondissement of Paris whom she had met at the Sorbonne in 1937. Three years her junior, he was called for military duty in 1938, shortly after graduating from law school, and sent directly to the front the following year. When he returned to civilian life in the summer of 1940, Robert Antelme had never been employed and now had to look for a job. Through the intervention of François Piétri, a first cousin of his mother who headed several ministries before the war and was now part of Vichy’s first government, he was hired by the Paris Préfecture de Police as a temporary assistant in the prefect’s office. (He would join the Ministry of Industry eight month later, before being reassigned to the Ministry of the Interior). François Piétri could have perhaps intervene at the Ministry of the Colonies on behalf of his young cousin’s wife, but at the end of that summer, as the government was reshuffled he was let go and sent to Madrid to succeed Marshal Pétain as ambassador to Franco’s Spain, a position he held until 1944.

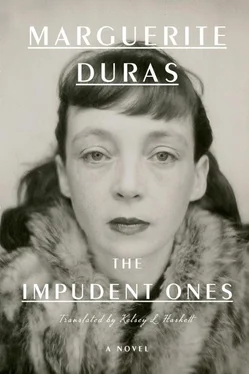

We do not know if Marguerite Duras was distraught at having lost her job, and with it her financial independence, or if she was happy to be able to devote herself fully to writing, thus realizing her early ambition (at the age of twelve, she had allegedly confided to her mother that she wanted to be a writer). What we do know, thanks to a membership card from the library of the University of Paris dated August 20, 1940, signed Marguerite Antelme, is that she was authorized to work in the reading room of the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève from that date until the end of November. This is when she wrote La famille Taneran , later to be renamed Les impudents , published now in English for the first time as The Impudent Ones . She may have started a first draft during her stay in Brive-la-Gaillarde, where she could discuss her work with her friend Pierre Lafue, but the bulk of the novel must have been written during the first fall and early winter of the German occupation.

The Taneran Family

This family is composed of the father and the mother (already advanced in age), of two sons and one daughter. The eldest of the brothers, Jacques is a mawkish lout, cowardly and spiteful; the younger one remains uncommunicative; Maud, the daughter, romantic, passionate, vindictive, who feels unloved or forsaken, in any case misunderstood, goes to live for a few weeks with a man she has met. Her mother comes to fetch her, does not upbraid her too much. The mother cares above all for her elder son, and, perhaps because Maud is fallen and no longer superior to Jacques, she does not blame Maud for this transgression. Maud, intending to show herself worthy of the baseness one attributes to her, denounces her brother to the police for a scam of fake bills of exchange. {3} 3 Gallimard archives.

Such was the less-than-glowing reader’s report on the manuscript for Gallimard, written by Marcel Arland, a distinguished writer and winner of the Prix Goncourt in 1929 for L’Ordre , a novel about another dysfunctional family in provincial France between the two wars.

Like so many first novels, The Impudent Ones is partly autobiographical. The portrait of the divided Taneran family found in this book also foreshadows the one the author would paint later in works such as Whole Days in the Trees and The Lover . Freely mixing fiction and reality, the family portrait is drawn here through the subjective memory of an aspiring writer trying to come to terms with an emotionally charged adolescence. {4} 4 In a copy of her book that she gave to her companion Dionys Mascolo in 1943, Marguerite Duras wrote: “This book fell from me: the dread and the desire born from the hard part of a childhood no doubt not easy.”

To write her novel, Marguerite Duras drew direct inspiration from events that had affected her and her family during the year they spent in France in 1931–32, and many details suggest that the story takes place in the early 1930s.

The main characters seem to have been modeled on the author herself, as well as on her immediate relatives. Under the English-sounding name of Maud Grant, the anguished heroine at the center of the story brings to mind a young Marguerite Donnadieu, only taller and more self-assured than she was at the time. In the same way, Mrs. Grant-Taneran was fashioned after her own mother, like her a widow with the first name Marie, and also advanced in age (Mrs. Donnadieu was then fifty-four, going on fifty-five).

Jacques, the dissolute troublemaker, is easily identified as a version of Pierre Donnadieu, Marguerite’s “hated” older brother. Although only four year her senior, he is made to be more contemptible in the novel by being past forty and still without any occupation or sense of purpose (Maud decries her brother’s “shameless desire… to live the way he wanted to”). The author’s late father was brought back to life under the insipid figure of Mr. Taneran, Mrs. Grant’s second husband, a civil servant who “at one time… had had a respectable career teaching natural sciences at the high school in Auch,” where he met his wife. Henri, the son they had together, can be viewed as a substitute for Paul Donnadieu, the author’s second brother, or as a salute to Jacques Donnadieu, one of her half brothers, to whom the novel is dedicated. {5} 5 Jean and Jacques Donnadieu, born respectively in 1899 and 1904, were the two sons Marguerite Duras’s father had from his first marriage. Although she knew Jean Donnadieu well at the time she wrote Les impudents , she would never meet his brother again after she returned to Indochina during World War I as a three-year-old child.

Читать дальше