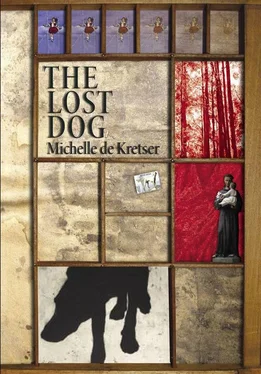

Michelle Kretser - The Lost Dog

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Michelle Kretser - The Lost Dog» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Lost Dog

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

The Lost Dog: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Lost Dog»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

***

‘A captivating read… I could read this book 10 times and get a phew perspective each time. It’s simply riveting.’ Caroline Davison, Glasgow Evening Times

‘… remarkably rich and complex… De Kretser has a wicked, exacting, mocking eye…While very funny in places, The Lost Dog is also a subtle and understated work, gently eloquent and thought-provoking… a tender and thoughtful book, a meditation on loss and fi nding, on words and wordlessness, and on memory, identity, history and modernity.’ The Dominion Post

‘Michelle de Kretser is the fastest rising star in Australia ’s literary firmament… stunningly beautiful.’ Metro

‘… a wonderful tale of obsession, art, death, loss, human failure and past and present loves. One of Australia ’s best contemporary writers.’

Harper’s Bazaar

‘In many ways this book is wonderfully mysterious. The whole concept of modernity juxtaposed with animality is a puzzle that kept this reader on edge for the entire reading. The Lost Dog is an intelligent and insightful book that will guarantee de Kretser a loyal following.’ Mary Philip, Courier-Mail

‘Engrossing… De Kretser confidently marshals her reader back and forth through the book’s complex flashback structure, keeping us in suspense even as we read simply for the pleasure of her prose… De Kretser knows when to explain and when to leave us deliciously wondering.’ Seattle Times

‘De Kretser continues to build a reputation as a stellar storyteller whose prose is inventive, assured, gloriously colourful and deeply thoughtful. The Lost Dog is a love story and a mystery and, at its best, possesses an accessible and seemingly effortless sophistication… a compelling book, simultaneously playful and utterly serious.’ Patrick Allington, Adelaide Advertiser ‘A nuanced portrait of a man in his time. The novel, like Tom, is multicultural, intelligent, challenging and, ultimately, rewarding.’

Library Journal

‘This book is so engaging and thought-provoking and its subject matter so substantial that the reader notices only in passing how funny it is.’ Kerryn Goldsworthy, Sydney Morning Herald

‘… rich, beautiful, shocking, affecting’ Clare Press, Vogue

‘… a cerebral, enigmatic reflection on cultures and identity… Ruminative and roving in form… intense, immaculate.’ Kirkus Reviews

‘De Kretser is as piercing in her observations of a city as Don DeLillo is at his best… this novel is a love song to a city… a delight to read, revealing itself in small, gem-like scenes.’ NZ Listener

‘… de Kretser’s trademark densely textured language, rich visual imagery and depth of description make The Lost Dog a delight to savour as well as a tale to ponder.’ Australian Bookseller and Publisher

‘A remarkably good novel, a story about human lives and the infi nite mystery of them.’ Next

‘Confident, meticulous plotting, her strong imagination and her precise, evocative prose. Like The Hamilton Case, The Lost Dog opens up rich vistas with its central idea and introduces the reader to a world beyond its fictional frontiers.’ Lindsay Duguid, Sunday Times

“[a] clever, engrossing novel… De Kretser’s beautifully shaded book moves between modern day Australia and post-colonial India. Mysteries and love affairs are unfolded but never fully resolved, and as Tom searches for his dog, it becomes apparent that its whereabouts is only one of the puzzles in his life.” Tina Jackson, Metro

‘A richly layered literary text.’ Emmanuelle Smith, Big Issue