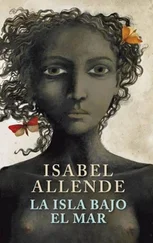

At the end of November, Toulouse Valmorain returned to Saint-Domingue to prepare for the arrival of his future wife. Like all plantations, Saint-Lazare had a "big house," which in this instance was little more than a rectangular wood and brick building lifted off ground level on three-meter pillars to protect it from slave uprisings and floods in the hurricane season. It had a series of dark bedchambers, several of them with rotted floors, and large drawing and dining rooms that featured opposing windows to facilitate circulation of breezes and a system of canvas fans strung from the ceiling and operated by slaves pulling a cord. With the back-and-forth of the ventilators a thin cloud of dust and dried mosquito wings was loosed to settle like dandruff on the diners' clothing. The windows had no panes, only waxed paper, and the furniture was rough, appropriate for a single man's interim dwelling. Bats nested in the ceiling, and at night one tended to encounter insects in the corners and hear the sound of mice in the bedchambers. A gallery, or roofed terrace, with battered wicker furniture enclosed the house on three sides. Around it were worm-eaten fruit trees, an untended vegetable garden, several patios with pecking hens befuddled by the heat, a stable for fine horses, dog kennels, a coach house, and beyond the roaring ocean of cane fields, as a backdrop, violet mountains profiled against a capricious sky. Perhaps once there had been a garden, but not even a memory remained. The sugar mills and the slave cabins could not be seen from the house. Toulouse Valmorain went over everything with a critical eye, noticing for the first time its rickety, vulgar appearance. Compared with the place Sancho lived, it was a palace, but measured against the mansions of the other grands blancs on the island, and his small family chateau in France, which he had not visited in eight years, it was embarrassingly ugly. He decided to begin his married life on the right foot and give his wife the surprise of a house worthy of the names Valmorain and Garcia del Solar. He would have to make arrangements.

Violette Boisier received the notice of her client's marriage with philosophical good humor. Loula, who knew everything, told her that Valmorain had a betrothed in Cuba. "He will miss you, my angel, but I assure you he will be back," she said. And he was. Shortly after, Valmorain knocked on the door of Violette's apartment, not in search of her usual services but to ask his old lover to help him receive his wife as she deserved. He did not know where to begin, and he could not think of another person of whom he could ask such a favor.

"Is it true that Spanish women sleep in a nun's nightdress with a hole cut in front for making love?" Violette asked him.

"How should I know that?" The groom-to-be laughed. "I am not married yet, but if that is true, I will rip it apart."

"No! You bring me the gown, and here with Loula we will open another hole in back," she said.

The young cocotte agreed to assist him if he paid her a reasonable commission of 15 percent on monies expended in furnishing the house. For the first time in Violette's dealings with a man no acrobatics in bed were included, and she set about the task with enthusiasm. She and Loula traveled to Saint-Lazare to get an idea of the mission she'd been charged with, and almost as soon as she stepped inside the door, a lizard from the coffered ceiling dropped into her decolletage. Her scream brought in several slaves from the patio, whom she recruited for a top to bottom cleaning. For one week this beautiful courtesan, whom Valmorain had seen only in golden lamplight, bedecked in silk and taffeta, made up and perfumed, directed the squad of barefoot slaves wearing a coarse cloth dressing gown and a rag tied around her head. She seemed in her element, as if she had been doing this rough work all her life. Under her orders the sound floorboards were scrubbed clean and the rotten ones replaced; she changed the mosquito netting and the paper at the windows. She aired the rooms, set out poison for the mice, burned tobacco to drive out insects, sent the broken furniture to the alley of the slaves, and finally the house was clean and bare. Violette had everything painted white inside, and as there was whitewash left over, she used it on the domestic slaves' cabins, which were near the big house, then had purple bougainvillea planted around the gallery. Valmorain promised her that he would keep the house clean. He also set several slaves to laying out a garden inspired by Versailles, though the extreme climate did not lend itself to the geometric art of the landscapes of the French court. Violette returned to Le Cap with a list of purchases. "Don't spend too much, this house is temporary; as soon as I have a manager we will go to France," Valmorain told her, handing her an amount he felt was fair. She ignored his warning, because nothing pleased her as much as shopping.

The bottomless treasure of the colony left from the port of Le Cap, and legal and contraband products came in. A many-colored throng rubbed elbows in the muddy streets, bargaining in many tongues amid carts, mules, horses, and packs of stray dogs that fed from the garbage. Everything from pirates' booty to extravagant Parisian items was sold there, and every day except Sunday slaves were auctioned off to supply demand: between twenty and thirty thousand a year just to keep the number stable, for they did not live very long. Violette spent her allowance but kept purchasing things on credit using the guarantee of Valmorain's name. Despite her youth, she made her selections with great aplomb; her worldly life had set and polished her taste. From the captain of a boat that sailed among the islands she ordered silver tableware, crystal, and a porcelain service for guests. The bride would bring sheets and tablecloths she had undoubtedly embroidered since childhood, so she did not worry about those. She bought furniture from France for the drawing room, a heavy American table with eighteen chairs destined to last generations, Dutch tapestries, lacquered screens, large Spanish chests for clothing, a surfeit of iron candelabra and oil lamps because she maintained that no one should live in the dark, Portuguese pottery for everyday use, a stream of frivolous embellishments, but no rugs because they would rot in the humidity. The comptoirs arranged to deliver and hand the bills to Valmorain. Soon carts laden to the top with boxes and baskets began to arrive at the Habitation Saint-Lazare. From the straw packing slaves extracted an interminable series of frills and furbelows: German clocks, birdcages, Chinese boxes, replicas of mutilated Roman statues, Venetian mirrors, engravings and paintings of various styles, chosen by theme, since Violette knew nothing of art, musical instruments that no one knew how to play, and even an incomprehensible collection of heavy glass and brass pipes and little wheels that, when put together by Valmorain like a jigsaw puzzle, turned out to be a telescope for spying on the slaves from the gallery. To Toulouse the furniture seemed ostentatious and the adornments totally useless, but he resigned himself because they could not be returned. Once the orgy of spending was concluded, Violette collected her commission and announced that he needed domestic servants: a good cook, maids for the house, and a lady's maid for Valmorain's future wife. That was the minimum required, according to Madame Delphine Pascal, who knew all the people of high society in Le Cap.

"Except me," Valmorain pointed out.

"Do you want me to help you or not?"

"All right, I will order Prosper Cambray to train some slaves."

"Oh, no, Toulouse! You will not save that way. Field slaves will not do, they're brutalized. I myself will look for your domestics," Violette decided.

Zarite was nearly nine when Violette bought her from Madame Delphine, a French woman with cottony curls and turkey bosom, along in years but well preserved considering the damages caused by the island's climate. Delphine Pascal was the widow of a minor French civil servant, but she gave herself the airs of a lofty person because of her relationships with the grands blancs, even though they came to her only for shady transactions. She knew many secrets, which gave her an advantage at the hour of obtaining favors. It appeared that she lived on the pension from her deceased husband and giving clavichord classes to young mademoiselles, but under cover she resold stolen goods, served as a procuress, and in case of emergency performed abortions. She quietly taught French to cocottes who planned to pass as white and who, although their skin was the appropriate color, were betrayed by their accent. That was how the widow had met Violette Boisier, one of the brightest among her students but one with no pretense of appearing French; to the contrary, the girl openly referred to her Senegalese grandmother. She wanted to speak correct French in order to be respected among her white "friends." Madame Delphine had only two slaves: Honore, an old man who performed all the chores, including those in the kitchen, whom she had bought very cheaply because his bones were twisted, and Zarite-Tete-a little mulatta who came into her hands when she was only a few weeks old and had cost her nothing. When Violette obtained her for Eugenia Garcia del Solar, the girl was skinny, pure vertical, angular lines, with a mat of very tight curls impossible to comb, but she moved with grace and had noble bones, and beautiful honey-colored eyes shadowed by thick eyelashes. Perhaps she was descended from a Senegalese woman, as was she herself, thought Violette. Tete had learned early on the advantage of silence, and carried out orders with a vacant expression, giving no sign of understanding what was happening around her, but Violette suspected she was much cleverer than could be seen at first glance. Usually Violette did not notice slaves-with the exception of Loula, she thought of them as merchandise-but that little creature evoked her sympathy. They were alike in some ways, although Violette had the advantage of having been spoiled by her mother and desired by every man who crossed her path. She was free, and beautiful. Tete had none of those attributes-she was merely a slave dressed in rags-but Violette intuited her strength of character. At Tete's age, she too had been a bundle of bones, until she filled out in puberty, her angles turned into curves, and the form was determined that would bring her fame. Then her mother began to train her in the profession that had been so beneficial to her, so she had never broken her back as a servant. Violette was a good student, and by the time her mother was murdered she was able to get along on her own, with the help of Loula, who defended her with jealous loyalty. Thanks to the good Loula, Violette had never needed the protection of a pimp and had prospered in an unrewarding profession in which other girls lost their health and sometimes their lives. As soon as the idea of finding a personal maid for the wife of Toulouse Valmorain had come up, she remembered Tete. "Why are you so interested in that runny-nosed little snipe?" Loula, always suspicious, asked when she learned of Violette's intentions. "It's a feeling I have; I think that our paths will cross some day," was the only explanation that occurred to Violette. Loula consulted her cowrie shells without getting a satisfactory answer; that method of divination did not lend itself to clarifying essential matters, only those of little importance.

Читать дальше