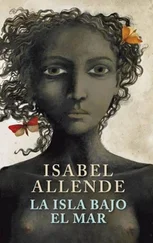

My daughter was born with open, elongated eyes, the same color as mine. She was slow to take a breath, but when she did her bellows made the candle flame tremble. Before she washed her, Tante Rose placed her on my breast, still joined to me with a thick cord. I named her Rosette for Tante Rose, whom I asked to be her grandmother since we had no other family. The next day the master baptized her by dripping water on her forehead and murmuring a few Christian words, but the next Sunday, Tante Rose held a true Rada service for Rosette. The maitre gave his permission for a kalenda and added a pair of goats to roast. So it was. It was an honor, because the birth of slaves was not celebrated on the plantation. The women prepared food and the men built bonfires, lighted torches, and played the drums in Tante Rose's hounfor, the healing center and sanctuary. With a thin line of corn flour my godmother drew the sacred writing of the symbolic veve around a central post, the poteau-mitan; that was how the loas descended and mounted several servitors, but not me. Tante Rose sacrificed a hen. First she broke its wings and then tore off its head with her teeth, as it is supposed to be done. I offered my daughter to Erzulie. I danced and danced, breasts heavy, arms lifted high, hips crazed, legs independent of my thought, responding to the drums.

At first the master was not interested in Rosette at all. It bothered him when she cried, and when I tended to her. Neither did he let me carry her on my back, as I had done with Maurice; I had to leave her in a drawer while I worked. Very soon he summoned me to his room again; he was excited by my breasts, which had grown to twice their size, and his just looking at them caused my milk to flow. Later he began to notice Rosette because Maurice clung to her. When Maurice was born he was a pale, silent little mouse I could hold in one hand, very different from my daughter, large and very loud. It had been good for Maurice to spend his first months pressed close to my body, like African children who, I've been told, do not touch the ground until it's time to learn to walk; they are always in arms. With the heat of my body and his good appetite he grew healthy and shook off the illnesses that kill so many children. He was clever, he understood everything, and from the age of two asked questions not even his father could answer. No one had taught him Creole, but he spoke it as well as French. The maitre did not allow him to mix with the slaves, but he would slip away to play with the few little blacks on the plantation, and I could not scold him for it because there is nothing as sad as a solitary child. From the beginning, he was Rosette's guardian. He never left her side, except when his father took him to ride around the property to show him his possessions. The master always put emphasis on Maurice's inheritance, which was why he suffered many years later at his son's betrayal. Maurice sat for hours playing with his blocks and his little wood horse near Rosette's drawer; he cried if she cried, he made faces at her and died laughing if she responded. The master forbade me to say that Rosette was his daughter, something that had never occurred to me to do, but Maurice guessed or invented it, because he called her ma soeurette, my little sister. His father scrubbed his mouth with soap, but he could not stop that habit the way he had cured him of calling me Maman. He was afraid of his real mother; he didn't want to see her, and called her "the ill lady." Maurice learned to call me Tete, like everyone else, except the few who know me inside and out and call me Zarite.

At the end of a few days of chasing Gambo, Prosper Cambray was livid with rage. There was no trace of the boy, and he had a pack of crazed dogs on his hands, half blind and with raw, sore muzzles. He blamed Tete. It was the first time he had accused her directly, and he knew that at that moment something fundamental was defined between him and his employer. Until then one word from him had been enough to condemn a slave without hope of appeal, and with immediate punishment, but with Tete he had never dared.

"The house is not run the same way the plantation is, Cambray," Valmorain explained.

"She is responsible for the domestics," the overseer insisted. "If we don't make this a lesson, others will disappear."

"I will take care of this my own way," Valmorain replied, little inclined to raise his hand against Tete, who had just had a baby and had always been an impeccable housekeeper. The house functioned smoothly, and the servants carried out their tasks well. Besides, there was Maurice, of course, and the affection the boy had for the woman. To flog her, as Cambray intended, would be like flogging Maurice.

"I warned you some time ago that that young black was a troublemaker. I should have broken him as soon as I bought him, I wasn't hard enough."

"It's fine, Cambray. When you capture him you can do what you think best," Valmorain said, while Tete, who was standing listening in a corner like a prisoner, tried to conceal her anguish.

Valmorain was too preoccupied with his business and the state of the colony to be concerned about one slave here or there. He didn't remember Gambo at all, it was impossible to distinguish one among hundreds. On one or two occasions Tete had mentioned the "boy in the kitchen," and Valmorain had the idea he was a runny-nosed child, but that could not be the case if he was that daring; it took balls to run away. He was sure that Cambray would not be long in catching up with him, he had more than enough experience in hunting down blacks. The overseer was right; they should beef up discipline, there were enough problems among the free blacks on the island without allowing insolence from the slaves. The Assemblee Nationale in France had taken from the colony what little autonomous power it had enjoyed; that is, some bureaucrats in Paris who had never set foot in the Antilles and who scarcely knew enough to wipe their asses, he would say with emphasis, were now deciding matters of enormous gravity. No grand blanc was willing to accept the absurd decrees being made for them. Who could believe such ignorance! The result was pure noise and disorder, like what had happened to one Vincent Oge, a wealthy mulatto who'd gone to Paris to demand equal rights for the affranchis and come back with his tail between his legs, as might be expected: where would things be if the natural distinctions between classes and races were erased! Oge and his crony Chavannes, with the help of some abolitionists-there were always some of them around-had incited a rebellion in the north, very close to Saint-Lazare. Three hundred well armed mulattoes! It took all the effort of the Regiment Le Cap to defeat them, Valmorain told Tete during one of his evening monologues. He added that the hero of the day had been an acquaintance of his, Major Etienne Relais, a man of experience and courage, but one with Republican leanings. The survivors were captured in a swift maneuver, and over several days hundreds of scaffolds were raised in the center of the city, a forest of hanged men gradually decomposing in the heat, a feast for the buzzards. The two leaders were slowly tortured in the public plaza without the mercy of a coup de grace. And it was not, Valmorain said, that he was party to cruel punishment, but sometimes it was instructive for the populace. Tete listened without a word, thinking of Major Relais, whom she scarcely remembered and would not recognize if she saw him; she had been with him only once or twice in the apartment on the place Clugny, many years before. If the man still loved Violette, it must not be easy for him to fight the affranchis. Oge could have been her friend or relative.

Gambo had been assigned the task of tending the men captured by Cambray, who were in the filthy barn that served as a hospital. The women on the plantation fed them corn, sweet potato, okra, yucca, and bananas from their own provisions, but Tante Rose went to see the master to make a plea-one that Cambray would certainly have refused-for the lives of these men who would not survive without a soup she would make of bones, herbs, and the livers of the animals that were eaten in the big house. Valmorain looked up from his book on the gardens of the Sun King, annoyed by the interruption, but that strange woman intimidated him and he listened. "Those Negroes have had their lesson by now. Give them your soup, woman, and if you save them I will gain by not having lost so much," he answered. Gambo fed them during the first days because they could not feed themselves, and distributed among them a paste of leaves and quinoa ash that Tante Rose said they were to keep rolling like a ball in their mouths to endure pain and furnish energy. It was a secret of the Arawak chieftains that somehow had survived three hundred years and that only a few healers knew. The plant was very rare; it was not sold in the magic markets and Tante Rose had not been able to grow it in her garden, which was why it was kept for the worst cases.

Читать дальше