“Look, Dad, not now-“

“Tell him,” he said to my mother, “tell him how long this has been going on with him.”

“Oh, not now,” said my mother, beginning to cry.

But he was fired up; miraculously, I was in the clear, and so he could finally let me know just how angry he was that I had squandered my familial inheritance of industriousness and stamina and pragmatism-all those lessons learned from him on Saturdays in the store, why had I tossed them to the wind? “No, no,” he would say to me from atop the ladder in the stockroom, as I handed up to him the boxes of Interwoven socks, “no, not like that, Peppy-you’re making it hard for yourself. Like this! Get it right! Always do a job right. Doing it wrong, son, don’t make sense at all!” All the entrepreneurial good sense, all that training in management and order, why hadn’t I seen it for the wisdom that it was? Why couldn’t a haberdashery store be a source of sacred knowledge too? Why, Peppy? Not profound enough to suit you? All too banal and unmomentous? Oh yes, what are Flagg Brothers shoes and Hickok belts and Swank tie clasps to a unique artistic spirit like yours!

“-it was a terrible thunderstorm,” he was saying, “there was thunder and everything, and you were in school, Peter, in kindergarten. Four-and-a-half years old and you wouldn’t let anybody even take you, after the first week, not even Joannie. No, you had to do it alone. You don’t remember this, huh?”

“No, no.”

“Well, it was raining, I’ll tell you. And so your mother got your little raincoat, and your rainhat and your rubbers, and she ran to the school at the end of the day so you shouldn’t have to get soaked coming home. And you don’t remember what you did?”

Well, at last I was crying too. “No, no, I guess I don’t.”

“You balked. You gave her a look that could have killed.”

“I did?”

“Oh, you did! And told her off. ‘Go home!’ you told her. Four-and-a-half years old! And would not even so much as put on the hat. Walked out, right past her, and home in the storm, with her chasing after you. Everything you had to do by yourself, to show what a big shot you were-and look, Peppy, look what has come of it! At least now listen to your family once.”

“Okay, I will,” I said, hanging up.

Then, eyes leaking, teeth chattering, not at all the picture of a man whose nemesis has ceased to exist and who once again is his own lord and master, I turned to Susan, still sitting there huddled up in her coat, looking, to my abashment, as helpless as the day I had found her. Sitting there waiting. Oh, my God, I thought-now you. You being you! And me! This me who is me being me and none other!

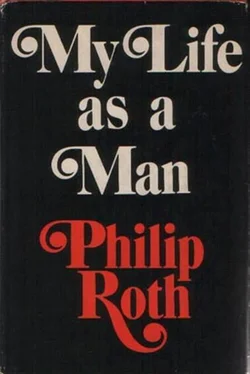

Philip Roth was born in Newark, New Jersey, in 1933. He is the author of eight books of fiction: Goodbye, Columbus (1959), Letting Go (1962), When She Was Good (1967), Portnoy’s Complaint (1969), Our Gang (1971), The Breast (1972), The Great American Novel (1973), and My Life as a Man (1974). Since 1965 he has been on the faculty of the University of Pennsylvania, where he teaches literature one semester of each year. In 1970 he was elected to the National Institute of Arts and Letters.

***