After an hour or so of that tune I was ready for the next. The fire was turning to a mush of red-hot ember as I passed quietly to the bedroom and placed another record on the turntable, songs by John Dowland, a lute player from Shakespeare’s time: I saw the first three titles circle on the label: Flow Not so Fast Ye Fountains, Come from My Window, Flow Now my Teares .

On the way out I poured hot water for coffee to keep myself awake and carried it on top of a pillow so I could lean back and see the sky without straining. Before I got too comfortable, I went into the barn and spread all the seed, the cracked corn and pellets for the birds, all of it across the floor and into the yard, and wedged the door open so they could get in and out. From the window I heard more scratches and wondered how the sound of the record could reach this far, then saw the bundle of wings unfurl in the light of the moon and the claws scratch the glass, and the small bird flung itself once more at the sky it couldn’t reach. You think the moon is the sun, you do, I smiled, and you should be asleep, and I walked to it with my coat spread wide. It scattered itself into the folds, caught as I closed them. Goodness knows how long you’ve been trying. I carried the soft punch of its feathers into the yard and opened wide, and it flew up and was gone.

Not long now.

I was restless as a man waiting for a performance, an empty hand stretched out too far for another hand, an ear lost between notes. There was only one thing for it, the pipe would calm me, that and another sherry. I stoked the fire first, then poured a glass and lit the pipe, puffing my way out to the clearing.

* * *

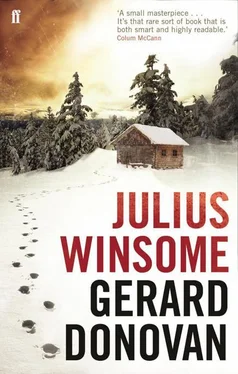

The wind came and slit me along the skin. This time I knew it for a snow wind, the way the trees rattled like fine silver, the sound of a trembling arctic sea across the tops of the forest. That same wind must have bounced off the trees and brushed the moon too, because when I looked up I saw it bulged slightly on the left side, like water in the thinnest reach of the wave when it spreads and then seeps, a bright salt stain on the sand.

My father’s astronomy book was correct to the hour in predicting the event to come, what he pointed out to me over thirty years ago one day when he told me to keep a look out for it. I said I would. Now here it was, the covering, the moon and sun and the earth arranged into a song, knowing nothing of the magic they made in the night. I let the book fall to my lap and sat back, my eyes steady on the shadow, the ground to which my chair and I were pinned, in which Hobbes lay curled, turning to cloth under us and spreading a giant cloak across the void. More wind blew like cutlery, a long, slow tinkling over Maine, what I would see if I rose up on wings over the forest, north to Quebec and east to Newfoundland, the bright foil of rivers, woods shook with frigid streams, wilderness run through with eagles, hawks, owls, bears, caribou, hungry herds gliding over the stones, the expanse of mountains and ice, roaming from night into day into night past wet towns nursed in valleys, the wide St. Lawrence salmon spearing ocean miles and river currents with a compass set for the narrow pond of their birth.

I passed an hour going from the clearing to the kitchen and back, more sherry, more music, more wood. And all the while the shadow passed across the moon until the reflected light dimmed to the color of paper, and then stone gray, and then burnt wood. And then there was no more in and out, and I was sitting in the big chair in the yard, arched for viewing through the trees with the pillow at my neck, the pipe in one hand, the book on my lap, the coffee in the other. Look at the hole in the sky, I thought, that was no giant glittering star in the night leading no men to their king. I waited, watching the faint stars find their places as the sun went behind the earth with all its light and switched off the moon.

When I felt the rushing through the woods behind me scurrying along the trails, I thought the whole world was sweeping itself clean in the vacuum, a piece of airless lightless space drenched down through the atmosphere. But it was just the snow wind again, this time reaching as far as the yard, and the first drops fell from the sky, from where I do not know, I saw no cloud. I was warm enough with the blanket and the coat, the gloves, and I wanted nothing on my head.

The truth was that I had lost track of the clock. I felt suspended in time not my own, not my choosing, a place I fell into by some omission or error, and grew. I might have risen then in my chair and be blown to the right time, backwards to an age I could breathe in, where my all waiting was right, a living place and pace, wine and hot meadows spread out under steeple bells.

Sitting in the chair, I watched the moon go a damp orange, then some blood seeped into it: and there it stayed, the true face of the moon, its true art, that cold, red flesh, a gunshot wound hung up in the night.

I watched it till I was so tired I had to close my eyes for a bit.

I had no logic, no excuse, no dreams that drove me to act or conjured a different man in me: every part of the last few days, everything I had done and not done, was my doing and mine alone. He was my friend, and I loved him. That is all of it.

* * *

When I woke, the cup had fallen, the book too, but the pipe still lay in my fingers. My ears were stones rubber-banded in skin, my lips and nose sore and numb at the same time. The moon had moved to the right and found its light, and the sky had collapsed, a good few inches of more snow fallen already, snow white-hot with light, snow on my coat, snow down one boot where the pants went inside, my sock drenched. Still I wanted to stay, to wait for morning, to cover myself and sleep the night out, but the fire was out for sure, and I wondered idly about the time.

I carried everything inside, the chair last, and resuscitated the flames. I watered the plants, stood briefly in my bedroom, bending over the mattress on the box springs, so much of my life spent unconscious there. The clothes in the closet were few, a couple of summer shirts. They could stay. An extra pair of summer shoes. Best leave them here. I turned the gramophone off and stored the record.

Since the cut in my shoulder was seeping red, I looked for some calendula in the bathroom cupboard. I opened the window, peered out then, and heard the hiss of dead brittle leaves. I heard the sound as if a name was being spoken, but the forest did not have a word for itself that I knew. And what was I to call myself now in any case? To the woods, I was doubtless a wound living in a clearing, a patch of infection.

I passed the books, so many books, and wondered how they would fare without a fire. Now they would all be cold books, if they stayed together. I stood by the chair and placed my grandfather’s pipe on one armrest, The Winter’s Tale on the other, then stepped out past the porch and glanced again at the grave, wondered if another Hobbes would grow in the spring, and who would be there to see it if one did. I did not care to be there: I should be wiped away, erased like pencil, cleaned like wood dust from the grate. They’ll have plenty to say now. What I wanted to say to that man as he walked ahead of me in the woods was that I didn’t have feeling where I should and too much where I shouldn’t. You keep away from men like me and you’ll be alright in life.

I meant to say that to him, but it never came up.

Five young deer ran in the moonlight between the trees. I saw their eyes shine as they passed the cabin, bunching briefly before loosening into a quick trot, an accordion of hooves bounding through the downy white.

I don’t know why but I waited a while watching the woods from the flowerbeds, as if Claire was going to come again out of the snow, for I had never figured how a woman who lived all those miles away in St. Agatha had ever walked out of these woods by accident.

Читать дальше