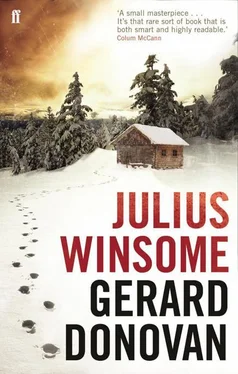

Not fifteen minutes later, deep in the New England chair on a Saturday mid-morning with my second sherry in hand and thirty-eight pages into Dickens, a bullet punctured the woods.

SOME PEOPLE WILL SHOOT ANYTHING, ANYTHING IN the world that moves, anything that flies, crawls or swims, anything of the living, furry, feathered, large, small, plump or scrawny, a grouse, woodcock, turkey, pheasant, white-tailed deer, black bear, moose, mice, rats, voles, rabbit, beaver, lynx, bobcat, raccoon, eastern coyote, muskrat, squirrel, otter, fox, mink, weasel, skunk, porcupine, they will do it on fine days, their favorite, on wet days, on days neither fine nor wet, though hunters love the chill in the air, the dank perfume of bark, the forest floor violets, the deer wandering the lakeshore in fog, it all triggers some deep delight in their blood, and if it makes them happy, then so be it, but my father often complained when the shots came five or six to a minute, saying it was hard to be reading in the middle of a broadside. We never heard the shriek of an animal, and that was at least something, but one day my father put down his book and paced the living room, hands behind him, his back slightly bent, his eyes a step ahead of his shoes on the floor.

He said, A battle sniper waits motionless for three hours for a second’s aim at a target that will shoot back or call artillery down upon him if he misses. These people out there, and he pointed out the window without looking, they shoot at targets taking a predicable course and without a return shot: you don’t have to worry about giving away your position, the flash of the gun muzzle, the steam off the barrel. The worst thing that can happen is you miss or hit but not fatally and they’ll go bleeding to find their young.

That was a lot for my father. Then he sat down and found his page again, but too late, I had heard what those shots had loosed in him. That night I dreamed of a feathery archer bending his bow to a nightingale in the branches of a cypress tree.

As a young boy of twelve or thirteen I often took walks in the woods around, though my father explained the places I could not go. One day off a trail forbidden to me I found rusted iron jaws chained to a tree and snapped shut on a leg. To the right in sunlit brush a mountain cat lay on its side. I clung to a tree in fright before seeing flies circle in the sunlight over the stump, a missing front leg. I ran home in tears. My father explained the mystery: the animal had stepped on a hidden hunter’s trap, and it chewed first through its own flesh and tendons, then the bone, and tore free. Those who did not, he said, pulled for a few days until hunger outpaced the pain, the string of convulsions, strange sights from the starvation, until they arrived at death and were calmed. He said that the cat’s ordeal was over. To the question I did not ask he added that some men must create pain in others to feel less of it themselves.

I soon came to a point in life when I watched for people who came too close to the cabin and the animals we kept. I was twenty or so when I saw a man with a 12-guage looped from his shoulder standing by the pond looking for something to shoot. We had a pet water fowl called Cinder who sometimes went down there, she’d lived on the farm for four years and her mate was somewhere about rummaging in the water basin to clean himself. I heard them calling to each other across the farm a few minutes before. So I stood at the treeline and watched this man. He looked forlorn, balding at the crown, with a tube in the middle, a flannel shirt rolled up and rough at the arms, staring still and silently at an empty pond ringed with plants. Maybe she was in there, he’d spy her and shoot, and she would not survive the blast of pellets. I made a movement and he looked up to me. I did not acknowledge him. He muttered and walked to his left along the pond and into the trees. I put water on for tea and waited for him to come back, since I suspected he was not to be happy that particular day unless he put an end to something. But I was wrong: that man did not return.

It seemed to me that the world and the people abroad in it would not be told where not to go. In summer I had a ring of flowers to stop the forest, in winter a ring of books to stop the cold, to retreat inside for the months of silence. And around me another living ring, the animals that grouped around because of the food I threw down, the birds that hoped for seed in winter and sang their hearts out in spring in return. They lived in a circle of maybe a hundred yards, and in the end they gave their bodies up in peace. I’d find a bird lying in the woods, a mouse curled up by a rock. I hoped I could die so well. Perhaps it is all instinct, men say this. But try stopping a man from doing what he wants: people will not be controlled, they will not be dissuaded, they are also chained to what is in their minds to do, that too might be called instinct. It whips us all.

I tried to read more, but another theme had inserted itself into my thinking. Mine was a minor life, no church steeple scratching at the clouds or joined to the streets of a town, no birthdays and weddings and weekends, a few flowers holding back the forest, a certain number of ducks and guinea hens crackling up in the branches at night. A life all of my own choosing. That thought brought me back to Hobbes, but I had never left him, nor he me. His loss scratched my stomach like burlap, my companion of those years, none to visit him where he lay with his small life, none to know what he was. And now these insistent shots, these reminders.

In the hour that followed, the gunfire came thick and heavy across the yard, the book in my hands. From the sound and the spacing I figured there were two shooters nearby, well within a mile, and whenever I lost myself in the novel, a pair of shots startled the words away brought me back, until my mind left the book altogether and returned to rifles. It became obvious to me that I may not have dealt with the hunter who shot Hobbes after all, that he might still be at large in the area.

Of the shots that banged relentless out of the trees, and closer now too in the last few minutes, one of the two had a familiar ring to it. Something stirred in me again, this deep measure that had the better of me. People were incapable of minding their own business, all this infernal noise they brought with them everywhere.

I feared suddenly that I had reached a time where life had taught me all it was going to or wanted to. From this point on it would be a circle for me, always the same again, and harder to bear at each turn of the wheel when it came round. If I had a child, or someone, I could have led them to what I’d seen and heard over the years, but that was not to be. Around and around, the life of Julius Winsome, day in and out.

I was being shot out of my father’s books.

Every year, more and more hunters, better equipped, venturing farther into property, not content to go home without taking something. And if I could not read with all this firing going on, then why have books? The idea caught hold of me, and perhaps because I had not eaten yet or the sherry had gripped my blood or because of the feeling in the air of an approach of some kind, visitor either of weather or man I don’t know, but I imagined myself going inside the house, grabbing a foot-length of books, as many as I could carry in one go, and bringing them out to the clearing and setting them in a stack at the edge of the flowerbeds. And again for the second foot of books, a stack every yard till I had a line of them stretched along the boundary with the forest. What use were books now.

If I did that, it would be best to burn them, not leave them for others, but no big blaze either with smoke everywhere, because in no time I’d have people running with buckets and good intentions, sirens tearing up the road. If I wanted attention, no better way to signal my name in the air than with a smoke blanket. More effective would be one small and secret burning, and then another and another, piles of incendiary words, until the entire library was gone without fuss or notice. Don Quixote? A man my father said had so much information in his head it conjured his mind outside of him. The Parliament of Fowles? Such grace was long gone, long of little use.

Читать дальше