Winfried Sebald - Vertigo

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Winfried Sebald - Vertigo» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2001, ISBN: 2001, Издательство: New Directions, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Vertigo

- Автор:

- Издательство:New Directions

- Жанр:

- Год:2001

- ISBN:978-0811214858

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Vertigo: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Vertigo»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Vertigo

The Emigrants

The Rings of Saturn

The New York Times Book Review

The Emigrants

Vertigo — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Vertigo», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

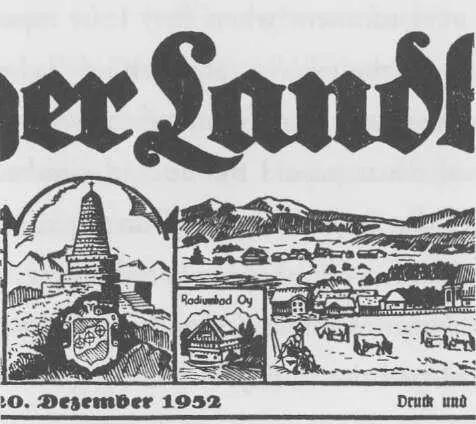

From such carnival exploits, our talk turned to Specht the printer, whose stationer's shop Lukas's wife was now running. For Specht, as Lukas said, had invariably still had his Christmas tree in his shop window when carnival week came round; indeed, that tree, which he had put up during the last week of Advent and which was now quite bare of needles, remained in the window not only until carnival but frequently until Easter, and on one occasion Specht even had to be reminded to remove the tree from the window in time at least for the Corpus Christi procession. Specht, who since the 1920s had written, edited, set and printed the fortnightly four-page newspaper Der Landbote, was an extremely introverted fellow, as is not infrequently the case

with printers. Moreover, the constant handling of lead type had made him ever smaller and greyer. I had a clear memory of Specht, from whom I had bought my first slate pencils and later the pens and the exercise books made of pulp paper on which the nibs constantly stuck when one was writing. Year in, year out he wore a grey calico coat which almost reached down to the floor, and round steel spectacles, and, whenever you entered the shop beneath the jingling bell, he would emerge from the printroom at the back with an oil rag in his hand. In the evenings, though, he could be seen sitting in the lamplight at the kitchen table, writing the articles and reports which were to be included in Der Landbote. Lukas claimed that much of what Specht wrote week after week for Der Landbote was rejected by him in his capacity as editor as not being up to the standards of the paper. Later on, when we had run out of Kalterer wine, Lukas took me around the house, showed me where Babett's and Bina's café, the Alpenrose, had been, where Dr Rambousek had his surgery, and where the bedrooms and the living room of the three sisters once were. As I was leaving, Lukas clutched my hand in the birdlike grasp of his gouty fingers for a long time, and I said that I would be glad to come over to see him more often so that we might talk further about the past, if he did not mind. Yes, said Lukas, there was something strange about remembering. When he lay on the sofa and thought back, it all became blurred as if he was out in a fog.

That same evening, over a second bottle of Kalterer in the Engelwirt, I was able to assemble some of my recollections of the Alpenrose. Whether it was Babett and Bina who had the idea of opening the café, or whether Baptist thought that it would support his unmarried sisters, was a part of the story that nobody could recall any more. At all events, there had been a Café Alpenrose, and it had continued until the deaths of Babett and Bina, although nobody had ever set foot in it. In summer, a small green metal table and three green folding chairs stood in the front garden under a pollarded lime tree which afforded a fine broad canopy of leaves. The door of the house was always open, and every couple of minutes Bina would appear in order to look out for the guests who would, surely, be arriving sometime. There is no way of telling what kept visitors away. Probably it was not simply because strangers, as summer guests were referred to in those days, hardly ever came to stay in W., but rather because the coffee house was run by Babett and Bina as a sort of spinsters' parlour which had nothing to offer the men of the village. I do not know, nor did Lukas know, what-sort of figure the two sisters had made at the beginning of their business venture. The only thing that could be said with any certainty was that whatever Babett and Bina had been at one time, or had wanted to be, was eventually destroyed by the years of continuous disappointment and perennially revived hope. The impairment to their lives which that destruction and their unending dependency on each other entailed ultimately led to their being regarded as no more than a pair of dotty old maids. Of course it did not help that Bina, smoothing down her apron with her hands, spent the hours running around the house and the front garden, while Babett sat in the kitchen all day long folding tea towels, only to unfold and refold them again. It was with the greatest effort that the two of them managed to keep their small household in order, and what they would have done if one day a guest had actually crossed the threshold is quite inconceivable. Even when making a pot of soup they were more of a hindrance than a help to each other, and the weekly creation of a cake for Sunday, Lukas told me, was always a major operation that took them the whole of Saturday. Nonetheless, whenever the end of the week was approaching, Babett would prevail upon Bina, as much as Bina prevailed upon Babett, that a cake should be baked once again, alternately either an apple cake or a so-called Guglhupf. Once the task was accomplished, the cake would be carried with some ceremony into the front room and there, virginal and freshly dusted with icing sugar, as it was, placed under a glass dome on the sideboard, next to the apple cake, or else the Guglhupf, that had been baked the previous Saturday, so that any guest who had happened by on the Saturday afternoon would have had a choice of two cakes — a stale apple cake and a fresh Guglhupf or a stale Guglhupf and a fresh apple cake. On the Sunday afternoon that choice ceased to be available, for it was always on Sunday afternoons that Babett and Bina consumed either the stale apple cake or the stale Guglhupf with their Sunday afternoon coffee, Babett eating the cake with a cake fork while Bina would be dunking hers, a habit which Babett deplored and which she had never been able to correct in her sister. After consuming the stale cake the two of them would sit for an hour or two, sated and silent, in the gloom of their parlour. On the wall over the sideboard hung a picture of two lovers in the act of committing suicide. It was a winter night and the moon had emerged from behind the clouds to witness this final moment. The pair, out on a narrow landing stage, were about to take their last decisive step. Together, the foot of the girl and that of the man were suspended over the dark waters, and one could sense with relief how both were now in the grip of gravity. I remember that the girl had a thin, viridescent veil draped over her head, while the man's coat was taut against the wind. Below this picture stood the cake intended for the coming week; the clock on the wall ticked, and whenever it was about to strike it gave a long-drawn-out wheeze, as if it could not bring itself to announce the loss of another quarter of an hour. In summer, the light of late afternoon entered through the curtains, in winter the falling dusk, and on the table in the centre, biding its time, stood the enormous aspidistra which the long years had left untouched and around which, in some mysterious manner, everything at the Alpenrose seemed to revolve.

My grandfather went across to the Alpenrose once a week to call upon Mathild. The two of them usually played several games of cards together and conversed at some length, as there was always plenty to talk about. They would sit in the front parlour, for Mathild did not allow anyone, not even Grandfather, up to her room; Babett and Bina, who respected Mathild as a higher authority, had become accustomed to remain in the kitchen during these visits. I often accompanied my grandfather to the Alpenrose, just as I accompanied him almost everywhere, and there I sat with a diluted raspberry syrup as the cards were shuffled, cut, dealt, played, placed to one side, counted and shuffled again. My grandfather was in the habit of wearing his hat while playing cards, and not until the last game was finished and Mathild had gone out into the kitchen to brew the coffee did he take off the hat and then wipe his forehead with his handkerchief. Of the matters discussed over coffee, there were few I had any notion of, and for that reason, once they started talking together, I generally went out into the front garden, sat on one of the chairs by the green metal table and looked at the old atlas which Mathild put out for me every time. In this atlas there was a page on which the longest rivers and the highest elevations on the surface of the

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Vertigo»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Vertigo» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Vertigo» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.