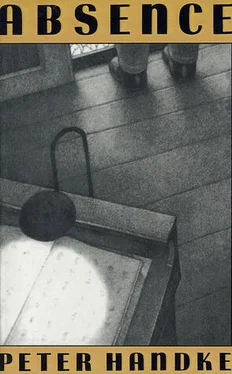

Peter Handke - Absence

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Peter Handke - Absence» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2000, Издательство: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Absence

- Автор:

- Издательство:Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Жанр:

- Год:2000

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Absence: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Absence»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

follows four nameless people — the old man, the woman, the soldier, and the gambler — as they journey to a desolate wasteland beyond the limits of an unnamed city.

Absence — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Absence», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

In the course of his speech the weather has changed several times, alternating between sunshine and rain, high wind and calm, as in April. One river crossed by the train, hardly a trickle between gravel banks, is followed by another, a roaring, muddy flood, which is perhaps only the next meander of the first. As so often on branch lines, the stations are farther and farther apart. Once, the train has stopped in open country. The wind was so strong that from time to time the heavy car trembled. Withered leaves, pieces of bark, and branches crashed against the window. When at last the train started up again, the lines of raindrops in motion crossed those of waiting time.

Surprisingly for a place so far out in the country, there are many tracks at the station they arrive at. All end at a concrete barrier; with the exception of the rails on either side of the platform, which have been polished smooth, all are brown with rust. The station is in an artificial hollow; a steep stairway leads out of it. The soldier carrying the woman’s suitcase, the four climb it together, more slowly than the few other people, all of whom are at home here. But even the newcomers are sure of the way. On leaving the ticket hall through a swinging door, they turn without hesitation in the direction indicated by the gambler, who has taken the lead. After crossing an area of bare ground and sparse, stubbly grass, suggesting an abandoned cattle pen or circus ground, they find themselves at the edge of a large forest. The trees in its dark depths seem at first sight to be covered with snow; in reality they are white birches. Here the four hesitate before crossing a kind of border, the dividing line between the yellowish clay of the open field and the black, undulating, springy peat soil. The peat bog and the forest rooted in it are also several feet higher than the field. Instead of a path cut through the earth wall there are several small wooden ladders, to one of which the gambler directs his followers with an easy gesture, showing that this is a man who gets his bearings without difficulty wherever he goes. He climbs up last, and once on top resumes leadership. Strolling through the woods — there is no underbrush between the birches — all four turn around in the direction of the station, toward which passengers are converging from all sides, all goose-stepping in a single file, though there is plenty of room in the field. Seen through the white trees, the shacklike structure seems to be somewhere in the taiga.

The forest is bright with birch light. The trees stand in beds of moss, as a rule several in a circle, as though growing from a common root. As one passes, they revolve in a circle dance that soon makes one dizzy. Over a footpath that suddenly makes its appearance — white stones sprinkled over the black ground — the four emerge at length into a wide clearing, announced some time earlier by the substitution of berry bushes for moss and by the widening middle strip of grass in the path. By now the path has become so wide that the four are able to walk abreast. On the threshold of the clearing, each of the four, on his own impulse, pauses for a moment; the woman has taken the arm of the old man, who nods his assent. Now they are fanning out in different directions, as though no longer needing a leader.

The clearing is rather hilly, shaped like a moraine spit thrust into the peat bog, and so large that the herd of deer at the other end goes right on grazing though the arrival of the newcomers has been far from soundless. Only the stag has raised his light-brown head like a chieftain. For a moment, his widely scattered herd looks like a tribe of Indians. In the middle of the clearing there is a small lake, which at first seems artificial but then — with its islands of rushes and black muddy banks, marked with all manner of animal tracks — proves to be a bog pool. Only at one point, at the tip of the moraine, so to speak, can the pool be reached dry-shod over gravel outcrops, and here its water, instead of presenting an opaque, reflecting surface, is perfectly transparent. The bright pebbles at the bottom stand out all the more clearly thanks to the glassy streaks in the water of the spring which emerges underground from the moraine and can be followed as it twines its way through the gravel to the lake which it feeds. This is also the place for a hut built of weathered, light-gray boards, shot through with amber-yellow or reddish-brown trails of resin, and for a strangely curved uphill-and-downhill boat dock that juts out over the water like a roller coaster.

Here, one by one, they all gather. The woman, the old man, and the soldier look on as the gambler fishes an enormous bunch of keys out of his coat pocket, unlocks the padlock on the hut, throws the door wide open, unlocks the glass-and-metal compartment inside it, and, after turning a last key, drives out in a car that gets longer and longer: a camper. Birch branches — camouflage and ornament in one — slide off the top.

He pushes open the back door, sets up a folding table on the grass, and spreads a white tablecloth over it. The soldier hastens to help him and brings four chairs from inside the vehicle. But for the time being no one sits down. The old man vanishes purposefully through the trees, the gambler goes into his camper, and the woman, again with her silver suitcase, signals the soldier to follow her to the boat dock. Standing behind him with scissors and comb that she has taken out of her suitcase, she changes his hairstyle. Then with a quick gesture she bids him take off his uniform and, repeatedly stepping back to scrutinize not so much the soldier as her handiwork, dresses him in civilian clothes, likewise out of her suitcase. She keeps tugging and pulling and plucking at the soldier, who doesn’t seem to mind; his transformation from a chubby-cheeked bumpkin to a smooth, ageless cosmopolitan, dressed for summer and ready for anything, seems perfectly natural; only his eyes, when he turns back toward the woman, are as grave as ever; behind the happily smiling woman, ever so pleased with herself, they see the old man, who has just stepped bareheaded out of the woods, his hat full of mushrooms. While the woman takes an awl — she has everything she needs in the suitcase — and makes an extra hole in the soldier’s belt, the old man, sitting beside them on the bank, cleans his varicolored mushrooms.

By then the table has been set for all. The gambler in the camper also seems changed, not only because he is officiating at the stove in his shirtsleeves and wearing a flowered apron, but also because for cooking he has put on a pair of half-moon glasses. It is only when he suddenly looks over the edges that his glance seems as cold and dangerous as it used to. In the cramped galley he moves with the grace of a born cook — carefully wiping the glasses, putting the plates in the oven to warm, reaching for the bunches of herbs hanging from the ceiling — and shuffles in and out of the camper as though he had been running a restaurant for years.

Meanwhile, the woman and the soldier are at the table waiting. The old man is sitting on a mossy bank with his canvas-covered notebook, inscribing his columns as though in accompaniment or response to the kitchen sounds. Then he too sits motionless, though without expectation, his strikingly upright posture attributable solely to the place or the light; there is no wind, but his cape is puffed out. A bottle of wine is cooling in the spring at his feet.

Now all four are at the table and the meal is over. The glasses are still there, but only the old man is drinking wine; the gambler and the woman are smoking; the soldier has moved a short distance away; resting one heel on the knee of the other leg, he is twanging a Jew’s harp rendered invisible by the hand he is holding over it — isolated chords with such long pauses between them that in the end we stop expecting a tune. As though in response to the music, the old man puts his wineglass down after every swallow, or waits with the glass in midair. Under his gaze the open back door of the camper turns into a cave, while the shingle roof of the boathouse becomes vaulted and shimmers like the scales of the fish that dart to the surface of the pool after scraps of food. Now the entire clearing has the aspect of a garden where time no longer matters. The only sounds to be heard are garden sounds, the fluttering of the tablecloth, the splashing of a fish, the brief whirring and chirping of a bird among the ferns at the edge of the forest. The clouds drift across a sky which becomes so high that space seems to form a palpable arch overhead. The blue between the clouds twists and turns and is reflected down below in the water, in the grass, and even in the dark bog soil.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Absence»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Absence» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Absence» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.