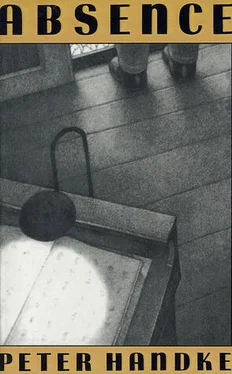

Peter Handke - Absence

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Peter Handke - Absence» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2000, Издательство: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Absence

- Автор:

- Издательство:Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Жанр:

- Год:2000

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Absence: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Absence»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

follows four nameless people — the old man, the woman, the soldier, and the gambler — as they journey to a desolate wasteland beyond the limits of an unnamed city.

Absence — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Absence», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The woman and the old man, who have taken their clothes off behind the camper, run down to the lake without a trace of embarrassment; the old man starts his run with a jump — like a child — and his way of running is equally childlike; the woman waits a moment, as though to give him a head start, and overtakes him at the brink of the water. The gambler and the soldier, each with a toothpick in his mouth, watch as the two swim out into the pond. The water is warm. The woman turns to the aged swimmer beside her and, speaking as though they were strolling down a path together, says: “I wish I could just stay here. Any other place I can think of would be too hot or too cold, too light or too dark, too quiet or too noisy, too crowded or too empty. I’m afraid of any new place and I hate all the old ones. In the places I know, dirt and ugliness are waiting for me; in the unknown ones, loneliness and bewilderment. I need this place. Yes, I know: it’s only on the move that I feel completely at home. But then I need a place where I can spread out. Tell me of one woman who lives entirely out of suitcases and I’ll tell you about all the little things you can’t help noticing the moment she arrives — a framed photograph here, a toothbrush there. I need my place, and that takes time. I wish I could stay here forever.”

Her swimming companion dives under; when he comes up, he has the face of a wrinkled infant. He answers in a voice made deep by the water, which resounds over the surface of the lake: “That wish cannot be fulfilled. And if it could be, it would bring no fulfillment in the long run. Whenever in my life I have thought I arrived, at the summit, in the center, there , it has been clear to me that I couldn’t stay. I can only pause for a little while; then I have to keep going until the day when it may be possible to be there somewhere else for a little while. Existence for me has never been more than a little while. There is no permanence in fulfillment, here or anywhere else. Places of fulfillment have hurt me more than any others; I have come to dread them. It’s no good getting used to staying in one place; wherever it is, fulfillment can’t last. It loses its magic before you know it, and so does the place. It is not here. We are not there. So let’s get going. Away from here. Onward. It’s time.”

The garden has undergone a transformation while the swimmer was speaking. Though the light is unchanged, the lake has taken on a late-afternoon look. The spring has almost dried up and the water level has fallen, uncovering the usual junk — tires, metal rods, whole bicycles — along with bleached, barkless tree trunks. The skeleton of some animal appears in the underbrush at the edge of the forest, and elsewhere a collapsed shooting bench comes to light; prematurely fallen leaves are blown over the springtime lake, and those soot-gray spots in the hollows are deposits of old snow. The clouds grow longer and are joined together by vapor trails of the same color; the faded scrap of newspaper in the bushes shows a distinct date; and that importunate noise is the persistent blowing of horns on an expressway.

The clearing is deserted, the boathouse sealed. The swimmers have left no trace in the wind-ruffled lake. Only the mud bank reveals the prints of bare feet and of the camper’s tires, vanishing in the gravel path as it mounts the moraine.

The four have been on the road a long time. As they sit in their camper with legs outstretched, it’s plain that they feel at home on the move. The gambler is at the wheel, the woman beside him is watching him; the old man and the soldier sit facing each other on the back benches, as in a minibus or cab. It’s not only the raised seats that give them the impression that they have been climbing; the light as well is an upland light, clear and spacious. And instead of a landscape, the naked sky appears in the side windows, yellow with sunset, hazy as though from smoke but in reality from dust. The bright gravel road, which the camper has all to itself, is bordered by a forest of diminutive trees, scarcely larger than bushes. In the fading light a dark tent city seems to extend to the distant horizon, where, as though on top of a barrier, the built-up center with its domes and towers and radio transmitters is situated. So tempting are the manifold forms of uninhabitedness that the four are determined to go there at once.

The area is not entirely deserted. A figure is standing by the roadside, signaling for a lift. The driver stops, and the hitchhiker, as nonchalantly as though getting into a bus, sits down in the back with the soldier and the old man. It is a woman swathed in a woolen headscarf, young, to judge by her eyes. The basket she props on her knees is empty, evidently she is returning home from a nearby market, where she has sold all her wares. (The only strange part of it is that she seems to have shot out of the bush, for there was no path at the place where she was standing.) Her presence underlines the feeling that this is a foreign country, but in what part of the world it is impossible to say. It could equally well be the far north or the deep south or somewhere in the interior; only the light of the particular moment lends any novelty. No attempt is made at conversation with the hitchhiker, communication seems inconceivable and undesired on either side. Only the two women have given each other appraising looks, then both turned away. The old man switches on a little overhead lamp — the light it throws on his notebook is very much like that on his lectern in the old people’s home — and tries to carry on with his signs, which the bumpy ride only makes more striking and picturesque. Before each of his strokes, always consisting of a single movement, he pauses for quite some time; shut off in his immersion, he looks at nothing else. Only the soldier, sitting across from him, manages to distract his attention. He too has a book in hand; it is still closed, and he makes elaborate preparations to open it. First he holds it out, eyes it as though to determine the right distance. What he does then is not so much to open it as cautiously to unfold it. He clamps a tiny, battery-operated reading lamp to the book cover and picks up the battery in his right hand, while with his left he places over the first line of text a semi-cylindrical glass rod, which magnifies the letters and lights up the spaces between them. The lamp sheds a tent-shaped light that makes the book appear transparent. For a moment it seems as though something is happening even without the reader. But the reader, sitting there so quietly, has his hands full, moving the magnifying glass from line to line and holding the heavy battery, which he hefts like a stone. He doesn’t even get around to turning the pages, the first page keeps him busy enough; each sentence takes time, and after each sentence he has to take a deep breath in preparation for the next. The reader reveals himself as a craftsman, and his dress, which only a short while before had seemed awkward on one who had long been in uniform, turns out to be right, a costume that leaves room for reading. Under the reading jacket his chest rises, his shoulders broaden, the mother-of-pearl button on his reader’s shirt shimmers, and the veins in his throat swell. The reader’s eyes are narrow and curve at the corners, widening at the temples as though the letters and words, though only a few inches away, form a distant horizon. These eyes show that it is not he who is digesting the book but the book that is digesting him; little by little, he is passing into the book, until — his ears have visibly flattened — he vanishes into it and becomes all book. In the book it is broad daylight and a horseman is about to ford the Rio Grande. As he watches the reader, the old man’s face copies his expression. He too has become all book, almost transparent.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Absence»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Absence» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Absence» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.