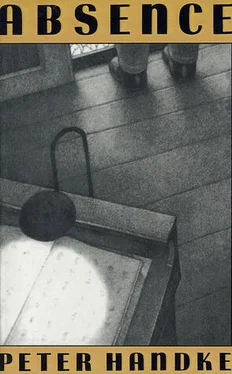

Peter Handke - Absence

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Peter Handke - Absence» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2000, Издательство: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Absence

- Автор:

- Издательство:Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Жанр:

- Год:2000

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Absence: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Absence»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

follows four nameless people — the old man, the woman, the soldier, and the gambler — as they journey to a desolate wasteland beyond the limits of an unnamed city.

Absence — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Absence», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The mute hitchhiker has long been gone; the wrinkles in her seat have smoothed out; it is black night in the moving vehicle. Now the woman is driving, with an expression at once vigilant and faraway; beside her the gambler, sitting upright but dozing off now and then.

The old man leans forward and motions the driver to turn off. The side road, almost entirely straight, descends steeply. The bushes are so close that they lash the roof and windows. Time and again the headlights pick a torrent, with frequent foaming rapids, out of the darkness. Just once the car comes to an almost level stretch, at the beginning of which there is a wrecked sluice gate with a chain still dangling from it, and at the end — indicated by a rotting wooden wheel with a few last stumps of spokes — an abandoned mill, its windows overgrown with hazel bushes, its loading ramp heaped with torn sacks and smashed bricks, and in the shed behind it an old handcart with upraised shafts, as though ready to be pulled.

They camp for the night at the spot where the torrent flows into a river which, in moonlight of a brightness seen only in old black-and-white Westerns, appears to be deep rather than wide. A wooden bridge leads across it, and on the other side a dark slope rises abruptly. This bridge was once an important crossing, perhaps even a disputed border, for at one end of it there is still a crank for a now-vanished barrier, and the plaster around the rusted flagpole sockets is riddled with bullet holes. But at the moment the place is almost completely forsaken, especially now at night; it’s not even a way station anymore; there has been only one late traveler, who was in such a hurry that he didn’t even stop to look at the camper.

Now it is parked on the stubbly grass between the road and a ruined building. Nimbly, the gambler and the soldier have made up the two bunk beds without once colliding in the cramped quarters. The interior is feebly lit by invisible lamps. From a radio in one corner, which seemed at first to be turned off, a voice is heard at intervals, rattling off frequencies and place-names, many of them overseas, in international radio English. The sound can also be heard outside — where the woman and the old man are sitting by a fire. She has slipped under his cape and is resting her head on his shoulder. But here the radio is almost drowned out by the murmur of the little waterfall at the spot where the torrent flows into the river. The river itself, by comparison, seems soundless, as though it had ceased to flow.

Now all is still in the camper, and the lights are out. The fire in the grass has burned down. The woman is still sitting by the ashes, but now the gambler is there instead of the old man, at some distance from her. The woman is warming her feet in the ashes and she no longer needs a cloak. At length the gambler breaks the silence: “That battered washtub over there on the bank, big enough for a whole family, has never been a household article. During the war the partisans used it as a ferry. They would paddle it across the river at night, not here, farther up. It often capsized, and a lot of them drowned — most of them were peasants who couldn’t swim; they had a secret workshop that turned out quantities of these washtubs. There’s no war memorial here. Nobody even knows that this ruin was the only electrical power station for miles around; the irregular current sparked and flickered in the region’s few houses, even in the farm at the tree line. The place is known only from a folk song which makes no mention of all that. It’s only about the name and a love that began here.” The woman has listened reluctantly, as though afraid of being lectured to; it took the key word at the end to relieve her fears; she wants no stories about places, only stories about love. The gambler takes his time, twists his ring, and says in a changed tone: “I didn’t respect you then, when you were brought before us in the amphitheater; I desired you. I wanted you. Your hopelessness was so complete, your brow gave off such a radiance, that I fell in love with you. Your despair aroused me. Then, when in your calm, friendly voice you told about your way of wandering around — the professor thought it was pathological — it came to me: I’ve found the woman of my life, something I had only dreamed of up until then; now it had happened. A decision was possible — actually, once you appeared, the decision had been made. In your hopelessness you struck me as immaculate, pure, holy, divine, and yet you were all woman, all flesh, all body, a perfect vessel. From my seat high up in the last row, I fell on you, I penetrated you with such force and to such depth that our ecstasy rose to the point of annihilation. And in your features, though I was sitting far away, I saw no difference between the face of extreme misery, the mask of inviolable feminine beatitude, and the grimace of utter lewdness. That day we loved each other before the eyes of all, I you in your forlornness, you me in my pure compassion. Since then I have had no feeling for anyone or anything. Since that day I have had no encounter with that rarest of all things, a beautiful human being. In that hour we, you and I, publicly engendered a unique child.” Whereupon the woman might have asked: “What sort of child?” And the gambler might have answered: “A child unborn to this day, perhaps already dead, perhaps unviable — a faint image, faint and becoming fainter.”

The woman has listened attentively to the gambler’s story. But from time to time she has shaken her head, as though the story were not to her liking, or in astonishment that such things were possible. And once she laughed, as though thinking of something entirely different. After the last sentence, she rummages in the ashes at her feet, finds a piece of wood that is still glowing, lights her cigarette with it; in the sudden glow her face is slit-eyed, masklike.

The full moon, at first yellow and huge on the horizon, is now small and white overhead, but its light is stranger than ever. Not only the whole breadth of the river glitters but also the leaves of the bushes on the banks; not only the metal parts of the camper but the wooden parts as well. The curtains are drawn, soft snores of varying pitch issue from them. Smoke rises from the ashes of the deserted campfire. In the gleaming water, a far brighter spot appears, a moving object; it crosses the river, shapeless at first, with a V-shaped glow in its wake. Mounting the bank, it shows the silhouette of an animal, too small and furry for a seal, too big and tail-heavy for an otter. The beaver crouches motionless; his eyes and ears are tiny and black as coal, his belly and feet are coated with clay. He sniffs uninterruptedly; he is the guardian of the site, he is guarding it with his sniffing. He is the master here now; he toils at night, damming the river; he has just come home from his place of work downstream.

In the morning it is summer. In the warm wind, the wall of foliage on the steep opposite bank has become a band of green, modulating from bush to bush, interrupted only in those places where the undersides of leaves shimmer pale-gray as though withered. The still half-dreaming ear mistakes the chirping of crickets for the din of cicadas. This bank as well is bathed in the light of high summer. In knee-length swimming trunks the old man stands under the little waterfall, which serves him both as shower and curtain; the woman sits with her eyes closed in a pool at his feet, quietly taking her bath, resting her head on a rock as against a bathtub; the water comes up to her chin.

The gambler and the soldier sit in the grass, playing cards. The soldier seems to be smiling, but his ears are deep-red, almost black, and oddly enough, the same is true of the gambler, who is sitting there in his shirtsleeves. The gambler shuffles, arranges his hand, plays and gathers the cards as eagerly and excitedly as if he had been a mere onlooker until then and had now at last been given a chance to play. He puts much too much energy into his movements for a friendly little game that is not even being played for money. The perspiration drips from his hair, and his shirt is plastered to his chest and back. He has taken to biting his nails when pausing to think; once or twice he tries to take back cards that he has already played — but here his opponent stops him, laying a firm hand across his fingers; and after losing he clasps his hands overhead and emits a loud curse. The woman, in a dressing gown, sits with them, applying makeup and taking it easy. The game, in which there is a winner but no winnings, has slowed all movements around it — in it they find their time measure — and, conversely, seems fenced in by slow time. What is outside the fence has lost its attraction, it frightens; there only the usual time can prevail, daily happening, history, “bad infinity,” never-ending world wars great and small. There beyond the horizon deadly earnest sets in, the treetops mark a borderline beyond which the lips of those who have just died quiver in an attempt to draw one more breath; bands of men and women, outwardly using words of endearment, inwardly mute, join forces, zealots of every kind, from whom there is no escape, who move even the highest mountains into the lowlands. One would like to regard the card game as reality and, thus fenced in, remain at the peak of time. The card players sit in the grass facing each other, as though they have shed their armor and for once are showing their true faces.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Absence»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Absence» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Absence» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.