“And be left not knowing the secret?” Julia said again.

“Never finding out how it all ended?” Genara supported her again. “Nobody leaves a movie without finding out how it all turned out. We can’t even stand for somebody to tell us about it later.”

“No matter the consequences?” Julia asked with the timidity of a novice.

Augusta did not reply. It was better, she thought, to leave the answer in the air. Or in the heart of each sister. She made a calculation. Genara could go. Julia and Augusta would remain. Julia and Genara could go. Augusta would remain alone.

The mere idea broke her impassivity. She felt real terror. Terror of absence. Knowing herself absent. Alone. Absent: stripped of inspiration or speculation. Incapable of even commemorating her own death.

How was she going to flee their father? Didn’t she know that ten years after his death, as soon as the secret of the inheritance was revealed, their father would impose a new time period? And what new surprise was waiting for them when they completed this one, and the next, and the next? Didn’t he once say before he went in for his daily sauna, “If I begin something, I don’t stop”?

The twelve strokes of midnight sounded in San José Insurgentes.

7. Six in the morning had sounded. Genara stretched. She had fallen asleep against her will. The beach chair was comfortable.

Poor Julia, sitting all night on a piano stool. She wasn’t there. Genara looked for her. Julia was putting on makeup, looking at herself in a pocket mirror. Pink powder. Purple lipstick. Eyeliner. Mascara. All arranged on top of the coffin.

Julia fluffed out her hair. She adjusted her bra. “Well, the next appointment is with the notary. We’ll see one another then. This business of a conditional will is so annoying! Well, we’ve fulfilled the condition. Now we’ll execute the will. Though we never lost our rights. . did we?”

“Unless we’re disinherited,” Augusta said from the shadows in the garage.

“What are you talking about!” Julia laughed. “It’s obvious you two didn’t know Papa. He’s a saint.”

Julia pushed the clanking metal door. Light from the sunken park came in. Birds were chirping. Julia went out. A Mustang convertible was parked in front of the garage. A boy in a short-sleeved shirt with the collar open whistled at Julia and opened the door for her. He didn’t have the courtesy to get out of the car. This didn’t seem to bother Julia. She got in, sat down beside the handsome young man, and gave him a peck on the cheek.

Julia looked young and agile, as if she had shed a gigantic bearskin.

She did not look back. The car took off. She had forgotten the revolving stool.

Genara smoothed her skirt and arranged her blouse. She looked at Augusta, wanting to ask her questions. She felt a hunger to understand. Julia would not explain anything to her. Julia’s world was resolved, free of problems. She was sure about inheriting. She had left.

Would Augusta explain things to her?

Genara took her handbag, a Gucci copy, and went toward the metal door. She insisted on looking at Augusta. The oldest sister did not return her look. Disorientation was etched on Genara’s features. She knew she could not expect anything of Augusta. She armed herself with patience. She was prepared to continue living her life decorously. In solitude. In front of the wheel. And then in front of the television set. With a cold supper on a tray.

“The three of us will see one another with the notary, won’t we?”

She put a foot outside the garage.

The foot stopped in midair.

8. Augusta did not see the actions of her sisters. Let them leave. Let them feel free. Let them run from their father. As if they could get away from him. As if the executors weren’t loyal to their father. What an idea.

Augusta will remain beside the father’s coffin. She will fulfill the funeral ritual until she herself occupies the father’s coffin.

She is the heir.

Choruscodaconrad

the violence, the violence

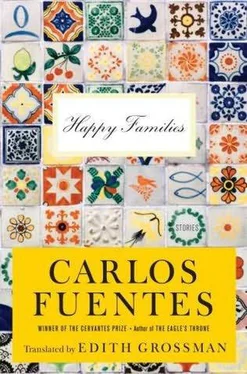

CARLOS FUENTES, Mexico’s leading novelist, was born in Panama City in 1928 and educated in Mexico, the United States, Geneva, and various cities in South America. He has been his country’s ambassador to France and is the author of more than ten novels, including The Eagle’s Throne, The Death of Artemio Cruz, Terra Nostra, The Old Gringo, The Years with Laura Diaz, Diana: The Goddess Who Hunts Alone, and Inez. His nonfiction includes The Crystal Frontier and This I Believe: An A to Z of a Life. He has received many awards for his accomplishments, among them the Mexican National Award for Literature in 1984, the Cervantes Prize in 1987, and the Légion d’Honneur in 1992.

EDITH GROSSMAN, the winner of a number of translating awards, most notably the 2006 PEN Ralph Manheim Medal, is the distinguished translator of works by major Spanishlanguage authors, including Gabriel García Márquez, Mario Vargas Llosa, Mayra Montero, and Álvaro Mutis, as well as Carlos Fuentes. Her translation of Miguel de Cervantes’s Don Quixote was published to great acclaim in 2003.