“Are you thinking of someone in particular?”

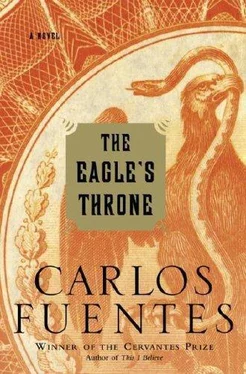

“I’m thinking of myself. I did nothing to get to the Eagle’s Throne. That was my strong point. I got there with no strings attached, no favors to pay back.”

“A process of elimination of sorts?” I dared to ask, with only a hint of impudence. He didn’t pick up on it.

“I got there just like Jesus,” he said, extraordinarily still, like an icon. “How many prophets and pseudo-messiahs were on the loose in Judea just like the son of Mary?”

Then, out of nowhere, he began to sing a line from an old Spanish zarzuela:

“Ay va, ay va, ay vámonos para Judea. . ”

At that, the parrot picked up on the tune in his shrill voice. “Ay ba, ay ba, ay Babilonia que marea. .”

I ignored these eccentricities.

“Yes, but that isn’t the rule, Mr. President.”

“Shut your mouth! Each president creates his own reality, but since the law against re-election forces him into retirement, this reality fades away and historical legend takes its place.”

He looked as if he were swallowing bile. Even the circles under his eyes seemed to be turning green.

“What happens? The ex-president is left with no power, but he’s still surrounded by ass-kissers. He doesn’t have to fool the people anymore. Now his aides want to fool him. They offer him the temptation of revenge. They intoxicate him with the idea that he’s incomparable, a cross between Napoleon and Disraeli.”

“ ¿Dónde vas con mantón de Manila? ” the parrot began to sing, and the Old Man whacked him so hard that the poor bird nearly went crashing to the floor.

“It’s like the old story about the whale and the elephant. The thing is, the poor slob ends up treating his allies like he treated his enemies. It’s a waste of time. Destroying them isn’t worth the effort. A lot of energy for nothing.”

He let out a sigh that the parrot didn’t dare respond to.

“Better to be alone and respected, even if they think I’m dead.”

There was a pregnant pause, as the Anglo-Saxons would say.

“Look at me here, drinking coffee and playing dominoes. I escaped the sad fate of most ex-presidents. I escaped the vicious cycle. And do you know why, Valdivia? Because I didn’t become president believing I’d be getting into bed with my own statue.”

He smiled as the parrot, having taken his punishment, sat once more on his shoulder.

“Don’t let that one get out. It’s the truth.”

“Mr. President, you were famous for shielding yourself with silence, for answering without speaking, for elevating the gesture into a sign of political communication, for turning the elliptical response into an art form, and the authority of your gaze into gospel.”

I looked him in the eye.

“I don’t want to waste time, Mr. President. I’ve come here for your guidance through the labyrinth of the presidential succession.”

Did I glimpse affection in his expression? Was he grateful for my attention, my respect, my interest? The look in his eyes seemed to say, I’ve known the depths of misery and disaster, and I’m the only one who left the palace without being disillusioned. . because I didn’t have any illusions in the first place.

“I never became disillusioned because I didn’t have any illusions in the first place,” he said, uncannily echoing my thoughts.

At that moment María del Rosario, your words came into my mind like a flash of lightning: “You will be president, Nicolás Valdivia.”

And I felt dizzy, as if I were on the edge of a cliff, seeing myself reflected in the Old Man. Was that how I’d end up as well, in a café in Veracruz, playing dominoes with a busybody parrot perched on my shoulder?

The vision sent me into a cold sweat in the middle of the sticky heat of the Gulf of Mexico.

The Old Man brought me back to reality.

“Do you think I didn’t know what kind of people I’d have to deal with as president? Damn it, Valdivia, the only cure for a hunchback is death, and in politics there are legions of them, all crooked, all of them incurable. They never straighten out, not even when they die.”

I was uncomfortable now. I scratched my back, I couldn’t help it— the Old Man’s tone of voice was so solemn, so gloomy, even fatal.

“As far as I’m concerned,” he went on, “a politician should be like a Japanese pilot: He should carry pistols but no parachute.”

He made an unusual gesture — a cinematic flourish straight out of an old Tyrone Power movie.

“Between the two extremes of Quasimodo and the kamikaze, I chose to be Zorro. The masked man everyone believes to be perfect.”

Did he sigh? I placed my two hands on the back of my chair.

The Old Man noticed and in a compassionate voice said, “Don’t rush. I haven’t breathed my last sigh yet. Oh, if you only knew how many times I’ve been taken for dead!”

I leaned forward. I took my chance.

“Don’t die on me without telling me first, Mr. President.”

“Tell you what?” the parrot said, as if he’d been preparing for that question all his life.

I had to laugh.

“The secret that you’re keeping.”

He didn’t move an inch. Unexpected or not, my question did not disturb him.

“Nobody should know everything,” he said after a long pause. “It’s not good for the health.”

“Don’t you mean, ‘Nobody can know everything?’ Isn’t that more to the point?”

“How straight you are, Mr. Valdivia. Get real. No, it’s not a question of can. It’s a question of should.”

“But we’re running out of time. I’m pleading with you now, like the young man you once were. Don’t send me back to Mexico City empty-handed.”

“I was never young,” he replied with a hint of bitterness. “I had to suffer and learn a lot before I became president. Otherwise I would have suffered and learned during my presidency and that would have been at the country’s expense.”

He looked at me with unconcealed scorn.

“Who do you think you are?”

He paused.

“You have to have lost a lot in order to be someone before and after you wield power.”

“But sometimes it’s the country — not the powerful leader — that loses with all that secrecy, intrigue, and personal ambition. And that’s what I’d call a catastrophe,” I said in the most dignified voice I could muster.

“Catastrophes are good,” said the Old Man, licking his lips like the Cheshire cat. “They reinforce the people’s stoicism.”

“Aren’t they stoic enough?” I asked, somewhat exasperated by now.

The Old Man looked at me with a mixture of pity, sympathy, and impatience.

“Look: Everyone thinks they can lock me up in an old age home. They underestimate my craftiness. But my craftiness is what makes me indispensable. The chitchat I leave to the parrot. You’re here because I know something everyone wants to know, information that could be critical for the presidential succession.”

He narrowed his eyes diabolically, María del Rosario.

“Do you think I’m going to spill the beans and let myself get thrown out in the garbage? Are you an idiot or are you just pretending to be?”

“I respect you, Mr. President.”

“What I said stands. I’m keeping my mouth shut.”

“Believe me, your honesty in no way diminishes the respect I have for you.”

He laughed. He dared to laugh.

“Comrade Valdivia, I believe in the law of political compensation. What I give with one hand, I take away with the other. If I give you what you want, what will I take away in exchange?”

Disquieted, I said, “Are you asking what you can expect from me?”

His response, lightning fast, was, “Or from the people who sent you here.”

Читать дальше