Josef K.’s existence is rooted deeply in order. At the bank, he can keep his clients waiting, even if they are important entrepreneurs. Time vibrates, “the hours hurtle by”—and Josef K. wants to enjoy them “like a young man.” A thought troubles him: will his superiors at the bank view him with sufficient benevolence to offer him the post of vice director?

Josef K. doesn’t know that all these facts predispose him to being put on trial. Like a fragrant, friable substance, he will during handling reveal new qualities, among them the pathetic beauty of the defendant — if it’s true that “defendants are the loveliest of all.”

Josef K.’s situation, as his trial begins, greatly resembles Franz Kafka’s in the spring of 1908. Both are brilliant employees. Kafka, younger by five years, is about to be hired, following flattering recommendations, by the Workers’ Accident Insurance Institute, after having resigned from another insurance company (Assicurazioni Generali). Both permit themselves to “enjoy the brief evenings and nights.” Kafka frequents the Trocadero and the Eldorado, eloquent emblems of the Prague demimonde. He once concocted a plan to show up in those places after five in the morning, like a tired, dissipated millionaire. Josef K. keeps in his wallet a photo of his lover, Elsa, who “by day received visitors only in bed.” Kafka recounts one of his late-afternoon visits to the enchanting Hansi Szokoll. He sat on the sofa by Hansi’s bed; her “boy’s body” was covered by a red blanket.

Hansi introduced herself on her calling cards as “ Artistin ” or “ Modistin ,” two terms sufficiently vague as to rule nothing out. According to Brod, Kafka once said of her that “entire cavalry regiments had ridden over her body.” Again according to Brod, Hansi made Kafka suffer during their “liaison.” We know this much for sure: they posed together for Kafka’s loveliest surviving photograph. Elegant in his buttoned-up frock coat and derby, Kafka is resting his right hand on a German shepherd that looks like an ectoplasmic emanation. But someone else is petting the dog: Hansi, whose figure has countless times been cropped out of the photo as if it were a Soviet document. She is smiling beneath a panoply of presumably auburn curls, topped by a little round hat. Kafka and Hansi are seated, posing, symmetrical. The out-of-focus, demonic dog sits between them — and their hands are almost touching.

According to Brod, Kafka in that photo has the look of one “who would like to run away the next moment.” But that’s a spiteful interpretation. His expression seems closer to absorbed melancholy. On the other hand we must be suspicious when Kafka smiles in a photograph, as in that silly pose at the Prater with three friends, facing a painted airplane. There Kafka is, in fact, the only one smiling, yet we know that in those very hours he was suffering from acute despair.

K. and Karl Rossmann are two figurations of the foreigner, he who sets foot in a world about which he knows nothing and through which he must make his way, step by step. But their gaze always retains, deep in their eyes, the reflection of another life. Josef K. is quite different: not only does he not start out as the foreigner, but he gets asked by his superiors to serve as guide for a foreigner who is passing through their city. The foreigner is he who is forced to understand, who must take it as his calling to understand, if he wants to survive. Josef K., on the other hand, is the native, and he’s completely at home in the bank where he works, to such a degree that he can be chosen to represent the company. It’s not required of him that he understand so much as that he submit to the order of which he is a part.

K. and Karl Rossmann live in a state of protracted wakefulness and chronic alarm. Josef K. is subjected to a forced awakening, thanks to two guards, who may even be impostors. The moment they choose is early morning, the moment that corresponds to physiological awakening. When the two kinds of awakening merge, one can be sure that a strange, ungovernable event is about to take place: everything is becoming literal. And so more dangerous. From the moment of his forced awakening, Josef K. is compelled not to understand but to recognize the existence of an ulterior world that has always been concealed within his city, mostly in anonymous, dreary places: the offices of the court that has issued the order for his arrest. With respect to that world, Josef K. will finally find himself in the position of the foreigner, a position he doesn’t like and hasn’t sought.

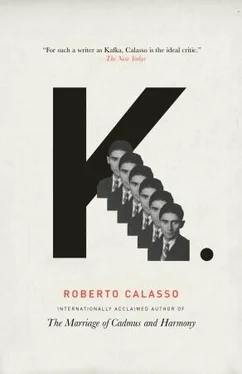

Josef K. thus has an acquired foreignness. He is the one forced to become foreign, whereas Karl Rossmann and K. are foreign from the start — Karl by order of his parents, K. by his own choice. Karl is the only one with a long line of precursors behind him: all those who, under adverse circumstances, have had to leave home and seek their fortune in the world. The antecedents of Josef K. and K., on the other hand, are not as clear, their relatives not as numerous. The simple K that marks them announces the disappearance of that jewel box of details that defines the Balzacian variety of novelistic character. That letter becomes an algebraic symbol, which designates a range of possibility. But this shift doesn’t imply a greater abstraction. Indeed, by now characters with thick identification files have become an atavism. Much more common is the cohabitation under the same name — or under the same insignia — of many people, even incompatible ones, who often cross one another’s paths without recognition, perhaps a few seconds apart, like daily riders of the subway.

Josef K. first grasps the gravity of his situation when he sees the two guards who have come to arrest him “sitting by the open window.” What are they doing? “They’re devouring his breakfast.” The verb Kafka uses, verzehren , is stronger than the usual essen , “to eat.” The voracity of the two guards presumes their total autonomy and the insignificance of whomever the breakfast was meant for. In an instant, life strips Josef K. of all authority. As with his breakfast, so with his undergarments, which the guards have already confiscated, going so far as to say: “You’re better off giving these things to us rather than the depository.”

No less intimate than undergarments, breakfast marks the end of the delicate phase of awakening and the entrance into the normal course of the day. But it is precisely this from which the guards want to exclude Josef K. From now on, he will have to remain perpetually exposed, vulnerable, defenseless, like a man just shaken from sleep who hasn’t yet got his bearings. Now he will have to get used to his new state, until it comes to seem normal. There will be no more breakfasts. At most, he’ll be allowed to bite the apple he left on his bedside table. The guards imply all this when they dip the bread and butter into the honey. For Josef K., this scene is like the gaze of the guard Franz: “likely full of meaning, but incomprehensible.”

When Josef K. realizes that two unknown persons have come to arrest him, he thinks at first that it’s all a joke, indeed a “crude joke,” being played on him by “his colleagues at the bank, for unknown reasons, perhaps because it was his thirtieth birthday.” He is comforted in any case by the thought that he lives “in a state governed by law,” where “peace reigned everywhere and all the laws were in force.”

And yet, when he withdraws briefly into his room, he finds it surprising — or “he found it surprising at least according to the guards’ way of thinking”—that “they had driven him into his room and left him alone there, where it would be ten times easier to kill himself.” Resuming then for a moment “his way of thinking,” Josef K. wonders “what motive he could possibly have for doing so.” He answers himself at once: “Perhaps because those two were sitting in the next room and had taken his breakfast?” This is the most delicate of passages. From the very beginning, Josef K. has tried to “insinuate himself somehow into the guards’ thoughts,” in order to sway them in his favor (a vice or virtue he will frequently indulge during the various phases of his trial). In so doing, he has discovered that his arrest is tantamount to a death sentence, and hence the risk of suicide, which would seek to preempt the sentence. But immediately following this insight, when he wonders about the possible motive for suicide, he reenters his own “way of thinking”—and it is there that he formulates the laughable hypothesis according to which his suicide might be provoked by the fact that the guards have taken his breakfast. Josef K. judges this thought “absurd,” and yet it’s the most lucid thought he has had so far: the sight of the guards devouring his breakfast implies that he has been notified of his death sentence. It implies too that notification and execution tend to coincide. The breakfast that the guards are devouring is already the breakfast of a dead man. By now the psychic commingling has begun; it will become increasingly difficult for Josef K. to distinguish between his own “way of thinking” and that of his persecutors. Blunders will become increasingly likely.

Читать дальше