Urvaśī and Purūravas’s room was always in shadow. But with two bright patches that sometimes melted together: two white lambs, tied to the sides of the bed. “They are my children,” Urvaśī had said. Purūravas had asked nothing more. They treated them with love, and fed them, but never let them loose. The bed, the lambs, Urvaśī’s and Purūravas’s bodies made a single pearly mass.

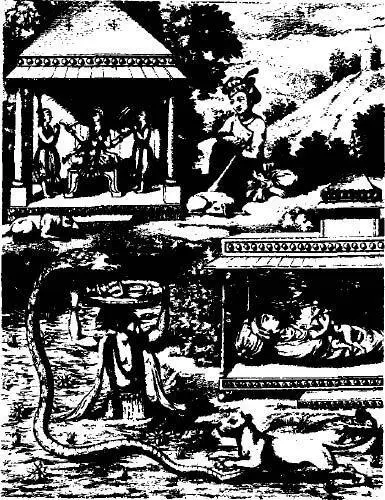

They slept. The lambs had curled up by the bed. There was a tearing sound, a feeble bleating. Then another tear, another feeble bleat. The lambs had gone. Without them the room seemed no more than a dreary shelter. Urvaśī sat upright, cold and angry, careless of her marvelously slanting breasts. “They’re taking away my loved ones… And there’s no man here to defend me.” Purūravas was deep in a sleep that was carrying him far, far away. Urvaśī’s voice came like a needle in his heart. With a shudder he leapt from the bed. He would rush off anywhere in his rage. There was a dazzling flash. For one long moment Purūravas’s body stood out in sharp silhouette against the air, completely naked. Thinking back on that moment — and he was to think back on it his whole life — Purūravas always experienced the same strange sensation: while he was suspended in the air, his entire body tense as an athlete’s, he was also fighting an elusive woman, very like Urvaśī, but hateful and mocking, who was grabbing his thighs and pulling off the white cloth he was never without. In that dazzling light, Purūravas felt someone, some creature he didn’t know, touching him, handling him, humiliating him. Then all was suddenly dark again. Purūravas rushed out. He came back with the lambs. “I’ve got them,” he said. But Urvaśī was gone.

This was the first time two lovers had ever been separated. For Purūravas it felt as though every sweetness had gone out of the world. He began to wander around. The earth at that time was a mass of vegetable decay. Ferns, riotous grasses, huge trunks fallen flat, plants growing on plants. What was missing was that liberating element: emptiness. Nothing was ever reduced to ashes, because fire was as yet unheard of. Purūravas found that nothing is so important as absence. He tried to get himself killed. He called for the help of some wild beast. Otherwise he would hang himself. Meanwhile he walked on, in no particular direction, ever further from anything he had known.

For some time he’d had no idea of his whereabouts when he found himself by a pond full of lotus flowers. Anyataḥplakṣā, in Kurukṣetra. It was majestically beautiful, but the only thing it offered him was a place to drown himself. Far away across the water, seven swans took shape. Purūravas paid no attention. As they approached the bank, Urvaśī said to her companions: “See that tattered man, with the feverish eyes… I lived with him for some years.” The other swans stretched out their necks, curious and incredulous. “Let’s make ourselves beautiful…,” said Urvaśī. Then they began to preen their feathers with great concentration. At the same time they were getting nearer and nearer the bank. When they touched the ground, they became Urvaśī and the six Apsaras who escorted her everywhere. But now they left her alone.

Acting quite naturally, Urvaśī sat down without a word on the grass next to Purūravas. Her lover lifted his empty eyes and recognized her. “Don’t disappear this time,” he said at once, as if afraid that Urvaśī were a vision. “You are cruel and dangerous, but we have some secrets we must tell each other. Otherwise, in times to come, we won’t have the joy that comes from having said them, at least once, in days gone by.” The stern Urvaśī raised her high cheekbones a fraction. In her contralto voice she said: “What’s the point of talking about it? I slipped away like the first of the Dawns. I’m like the wind, you can’t hold me. Go back home…” Purūravas gazed at her, her hard, elusive beauty: he remembered their first days together, when Urvaśī had begged him to keep her with him and it had been he who wasn’t interested. He had agreed to live with her out of curiosity, and for the vanity of having a divine being beside him, but always thinking of her as a stranger, who could be ditched the morning after. “All right,” he said. “Your friend will be off on his way. I am a companion of death, and I shall know where to find her. There must be some wolf willing to tear me to shreds. If not, I can hang myself.” The trap worked. Urvaśī’s expression was changing. A look of suffering rippled across her features. “Purūravas, don’t die. Don’t get yourself killed. But don’t believe in friendship with women: they have the hearts of hyenas. Go back home.” Purūravas was exultant, because he could see that Urvaśī was giving in. And at the same time he was still afraid she might disappear from one moment to the next. But Urvaśī went on speaking, albeit as though in trance, and to herself more than to him. She recalled the years they had lived together. Pervaded by her presence, Purūravas wasn’t even listening. All he heard were her last words: “I still remember those drops of cream you offered me every day. I can still smell them. It gives me joy to remember them…” Urvaśī had yielded. But immediately she recovered that lucid, determined expression Purūravas had noticed when they’d made their first pact. “All right, from now on we will meet for one night every year. We will have a son. It will be up to you to come to me this time, in the golden palace of the Gandharvas.” Speaking these words, Urvaśī was almost sad, as though thinking: “Of course, it won’t be so fine as before, when we had the two lambs tied to the sides of the bed. But it is all we are allowed…” Then she added: “Tomorrow the Gandharvas will grant you a favor. They are my lovers, they are jealous, it was they who stole me from you. But they will grant you the favor of becoming one of them, one among many. Accept. What matters, for you, is not so much to become a Gandharva, but what you will have to do to become a Gandharva.”

The following day, as solicitous as they were diffident, the Gandharvas explained to Purūravas what he and indeed all men and the earth were lacking: fire. “As a companion of death,” they said, “and you are all companions of death,” they insisted, “you can never gain access to the sky without fire.” That was why the earth was heavy and dull. It knew nothing but growth and decay. Now it would finally be able to destroy, and to destroy itself.

Purūravas went back to earth holding the hand of his son, Āyus, born of Urvaśí. In the forest, not far from his old home, he left the fire and the pitcher the Gandharvas had given him. Before performing what he knew would be a fatal act, he wanted to see the house he had left. He showed it to his son, who thus far had known only the sky and its palaces. A squeaky door opened onto a huge, empty room, full of dust. Against the far wall, a big bed. On the sides at the bottom, Purūravas recognized two hooks and two broken ropes. He said nothing, weeping inside. He went back to the forest with his son. The fire was gone. In its place he saw a tall fig tree, an aśvattha stretching its branches toward him. He broke two twigs off, like a sleepwalker. He rubbed them together, sensing that something was rising along each piece of wood, as when he used to go to Urvaśī’s body and brush himself against her. A light spurted, and it was fire, forever. From that day on those two twigs — and all other pieces of wood later used to make fire — were called Purūravas and Urvaśī.

Читать дальше