Then she said when did I want to get the patch sewn on, and I felt so good, because our group of friends was so tight. We helped each other. It was like we had a code, a way of doing things. A way we treated each other. I’d known when I’d picked up the phone to call her that she would eventually say yes to sewing on my patch, but she’d give me a hard time first, and if I stuck with it and stayed cool, it would all turn out nice. And that was exactly how it happened. There was for me in that time a real comfort in feeling a sort of casual ability to predict the future.

I said I could probably come over later that evening, and she said: “You’re so lucky you have cool parents,” and I pictured my parents: how they looked at me now that my hair was long, how they looked at each other a lot when they were talking to me. How obvious it seemed to me that somewhere along the line our paths had forked, and now we were on different tracks looking at each other across a distance that would soon be infinite. Cool parents, I thought, are the ones who know nothing. It made me feel a little sad for mine, but I didn’t say any of this. I had a funny feeling that day, all day: something about how much I liked my life and where I was with it.

So I told Kimmy I would come over at seven. She said, “If I sew your patch on you owe me.” And I said, OK, cool, I’ll see you there.

Lying on my bed, I listened to the Conan tape on my tiny cassette radio. There were ten songs by ten different bands or people on it, nobody I’d ever heard of. Some were just guys with acoustic guitars telling stories and some were bands with loud guitars and maybe a violin in there howling and squealing away. One was just a guy playing an organ with no singing at all. Mostly it sounded very cheap, but some of them were trying very hard to make something that sounded majestic and mighty. I loved it; nobody I knew listened to stuff like this. I looked at the tape shell, trying to think about all these people I didn’t know anything about from somewhere way up north, making music for people who cared about Conan. And I picked one of them at random to make a little mini-poster for, a band called Crom.

First I drew a picture of a skull, and then I put a helmet with horns over the skull. Then I put little flames inside the eye sockets. You couldn’t really see the flames unless you were looking for them. I did the whole thing with a mechanical pencil, and when I looked at the flames, they were still too clear; I wanted the eyes sitting way back, so they looked out from somewhere so far inside that looking into them would require real concentration and effort. I tried different shapes for the flames, first rounder and softer and then little pyramids almost, and then I went with little diamonds instead. You could only see the diamonds if you leaned in super close. The sockets were otherwise completely black.

At the table, Mom asked what I’d been drawing when she came to get me for dinner, and I pretended I didn’t know what she was talking about. It was like walking a tightrope. I’d been lying on my bed with the sketchbook open and several different pencils at hand for different shadings, and she’d knocked once and then opened the door; as soon as I’d heard the knock, reflexively I closed my notebook, just to be safe, I’m not sure from what, but I was still there with a notebook in front of me when she came in.

“The thing you were drawing, just now, when I came to get you.”

“I can’t draw,” I said.

“But you were drawing something, weren’t you? When I came in, just now,” she said.

“Not really,” I said. There are planets so far away from ours that no scientist will ever guess that they exist, let alone know the stories of their civilizations, their beginnings and ends. They’re not being kept secret from us, but they’re secret all the same.

“All right,” said Mom, looking over at my father for support, but he wasn’t paying attention. The TV was on in the living room, and he had a sight line to it from his chair. He was watching the news. I didn’t know why my dad liked to watch the news, because it made him angry, and the angrier he got, the louder he’d have to turn up the volume to hear the news over the things he yelled back at it. It got louder over the space of two hours most nights, and then the news was over. This made the house during dinnertime feel like an insane asylum.

Every night now there was new stuff about Libya. The CBS Evening News would show short clips of Gadhafi, who was president of Libya, or king, it was never clear to me. He was usually in sunglasses. Sometimes he’d be wearing a weird scarf bunched up around his neck, sailing out on the open sea somewhere maybe, or else riding around the streets in a military van. Everyone around him would always be smiling and sometimes yelling. You couldn’t see his eyes through the lenses, so it was hard to say what was going on in his head, but I always imagined he felt good. He looked like a white point in a map of a moving weather system. Cameras pointing at him, people yelling questions constantly, and him just standing amid it all holding his head still, waiting to see what he had to say, and sometimes speaking, subtitles quietly translating on the screen.

My father hated him; a bomb had gone off in the Vienna airport at Christmas, and the story’d been on the news every day for a week. Mom and Dad had gone to Vienna for vacation once before I was born, so for my dad this made the whole thing personal. He’d try to explain the stories to me as they ran, to get me excited about them like he was: and I’d try; I’d nod and pay close attention as his voice rose. But I couldn’t make myself care much about it: it seemed like nothing; I couldn’t keep any of it straight. The jagged, blurry pieces of footage spoke to me a little; there was something in them like a code or a secret message, not for me necessarily but for somebody. Or maybe for nobody, but hidden there all the same. But I didn’t know how to steer the conversation that way, or what I’d say about it if I succeeded.

We were having meat loaf with tomato sauce. I didn’t like meat loaf, but my mother remembered that I’d loved it as a kid. If I ate too slowly she’d say: “You used to love meat loaf!” I never knew what to say back, though that night I tried “It’s good” while stuffing a forkful of peas, potatoes, and meat loaf all into my mouth at once. I tried to remember liking meat loaf as a kid; for my mother the memory was so vivid she couldn’t forget it, but I couldn’t remember anything about it. At all. I knew we’d eaten it a lot, because you could make a pound of meat last longer by making meat loaf with it, but the only taste I could think of was the one I was trying to mask by eating everything on my plate at once. It was sad. “I like the sauce,” I tried again.

Then the story on gas prices came to an end, and they started in on Gadhafi. It had something to do with ships in foreign waters. “American ships in Libyan waters” was how it started off, and that was all I really heard: everything else receded quickly into the background for me and became nothing within a few seconds. Libyan waters. Dad watched while he ate and Mom watched his face nervously, and I wondered to myself whether waters take on special qualities depending on who they belong to.

I went out on a limb.

“Dad,” I said when the commercial started up, “are Libyan waters different from other waters?”

“Sean,” said Mom.

“They’re different because of sovereignty,” he said, keeping his eyes on his plate.

“Bill,” said Mom.

“But there aren’t any actual lines on the water or anything,” I said.

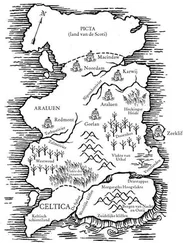

“They have maps and coordinates,” my dad said.

“Right, but the water—”

Читать дальше