I got a phone call, anyway.

“A colleague of mine has been working on this new surgical technique people are having pretty good results with,” said my old doctor. “He’s had several patients, burn patients, you know, people with really significant trauma, and they’ve been able to live a, you know, a less secluded life.”

I put on my glasses and I looked in the mirror.

Chris told me about the scalpel and the cyst as he prepared to launch an assault on the men in the gas masks by the overpass. Almost nobody began their play by attacking the cleanup guys; it was a nearly suicidal move. But Chris’s involvement in the game, the intensity of it, was so total from the outset that it was hard to know what to think about it. I pictured him acting out his dreams in real space, pantomiming his moves in a room somewhere before he wrote them down. I’ve got this cyst on my arm , he wrote; it’s gonna be a problem but I grabbed a scalpel off a crashed ambulance when the fallout hit. It was shocking stuff; this was his first full move.

I actually had a scalpel in the kitchen. I saw someone use one on a cooking show once and it looked cool, and since I have to get gauze and Betadine from the medical supply store every so often, I’d picked one up the next time I went in. They didn’t blink.

I used it once or twice to peel some oranges, and then I kept it on the desk for a while for opening letters. Using a scalpel to open my mail was a little more theatrical than I’d usually get in my daily life, the sort of thing people might imagine about me that wouldn’t turn out to be true. But really it was an accident. It sounds sad to say “It gave me something to do,” but it gave me something to do.

It’s gone now, anyway. I sent it to Chris a few turns after he’d described his impromptu surgery. I ought not to have done this; I am pretty careful to avoid acting on the spur of the moment. But it felt like a fun and probably harmless improvisation, a tiny thing conceived of on a moment’s notice. Still, I’d had to pack it up in bubble wrap, and find the right sort of box, and sending it required a trip to the post office instead of just placing a stuffed SASE in the mail slot on the door. That so much planning was necessarily involved is troubling to me; I don’t like to think about it. I can tell this is the wrong move I don’t care!! Chris had written at the end of that first turn. I can’t play through this with this burly knot on my arm!!! And immediately, wide-eyed, I’d seen the playfield as it must have looked to him, really letting myself take in the full view of it through what felt like his eyes.

He never mentioned it again; I thought I understood why. It was a question of style. I put it, for the most part, out of my mind. Sometimes I’d remember when his turns would get long and intricate. I get out the scalpel to kill snakes but there aren’t any snakes actually in snake landing so I look pretty stupid , he wrote once. No you don’t, I thought before I could stop myself from thinking it. No you don’t.

At home we worked out the mechanics of my situation, setting terms; my parents were very angry with me, and would stay angry for a long time. The air in the house would stink of blood forever; we’d breathe it as long as we lived there; new carpets didn’t really help. There was nothing anybody could do about it now. Even if I could’ve explained myself, anything that felt like an overture toward pressing the issue was visibly too painful for them to stand.

I would take the California High School State Proficiency Exam; this was an important point to both of them. I would go to therapy weekly, all of it: physical therapy, talk therapy, the dermatologist. I’d talk to the job placement people whose contact information the social worker had sent home with the discharge papers, and if they found me work, I’d take it to save up money. Dad would work out my monthly payout with the insurance people and send it directly to me to help with rent once I’d found a place. I told them about the game I’d come up with in the hospital, how I thought it might bring in a few hundred dollars a month if people liked it; they didn’t really try to hide their doubts, but they said that if it came to something, they’d support me in it. In a canvas tote from the hospital I had the papers I’d put together framing the full expanse of the Trace. They bulged in notebooks and folders that bore the hospital’s name and its little futuristic logo, a stylized cross that doubled as a letter.

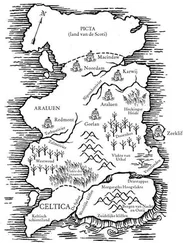

Over the course of the next month the house took on its own atmosphere, like a terrarium for fragile plants. I worked in earnest all day and into the night, sketching maps, writing turns. I stayed inside; the sun rising and setting outside my bedroom window became the sun of the Trace Italian, climbing the sky to illuminate the wasted plains of the near future, sinking down behind the western hills at night and leaving endless streaming dark in its wake. After I’d become adept with crutches, and later, when I walked, I’d go out to the front porch in the morning sometimes before the rest of the world was awake, thinking about the elaborate architecture of my invented world, how most of it lay east of here, in places I’d never see. Sometimes I’d turn my head left to look a little north, which always felt like the direction of the cold to me; ever since I was a kid and heard about the North Pole, where the snow never melted, I’d feel chills looking up toward Mount Baldy.

Chris followed a northward path when he first started playing. Lance and Carrie did the same thing a few years later. I took note of it at the time, but it was a connection I drew in the wrong place, like a surgeon putting an X on the wrong leg just before somebody fires up the saw.

I don’t save everything. It would be impossible to save everything. From the busiest days of the game, starting in the summer of 1990, there’s almost nothing left. Once I had boxes full of excited dispatches from across the country and occasionally even farther off: Mexico, Canada, Germany. But I cleaned and culled and thinned, and things lose meaning over time.

I grabbed a copy of The Watchtower from a small stack left on top of a PennySaver dispenser outside the Golden Arcade on the day of the accident, though, and I’ve saved it in a shoe box I keep near my desk. There’s a story called “Who Hid the Dead Sea Scrolls?” in it. It has underlined phrases and half-sentences running through its three short paragraphs: Sets out to reveal. Brought the bundles or sackfuls of texts from the capital to the desert caves for hiding. “All flesh is like grass, and all its glory is like a blossom of grass.” I don’t remember reading it or underlining anything, which troubles me, which is sort of why I keep it.

I used to save these Xeroxed handbills some crazy person attached by thumbtack to local telephone poles warning about the imminent colonization of Earth by aliens; there’s a few of these in the box, too, and some toys from the cheap toy dispensers you find in grocery stores. There are, finally, a few tapes, things a little too close to the bone for me to listen to but which I don’t want to throw away; and a letter from Chris from right around when he started reaching depths I hadn’t really foreseen. The turn he was answering had ended, You see the horde of misshapen half-human creatures on bony horses. North toward Oregon they ride, always at night or in the waxing dusk, evading the hungry outsiders who kill horses for meat and their riders for sport. You see packs slung astride the horses. There’s some brush just east.

These guys can’t touch me I’m going to live forever , Chris says toward the end of his second page, preparing to hurl himself upward and face-first toward the riders who weren’t supposed to pose any threat, who had no designs on him down in the dirt in his overnight lair. I remember reading this letter and closing my eyes, both seeking out and fleeing from the sharp memory it called up, unable to decide where to go, where to put the parts of myself it seemed to make manifest in the room.

Читать дальше