My parents looked at the doctor; the doctor looked at me. The social worker looked down at her clipboard and shuffled a few papers from the bottom of her stack to the top, and she started in on Mom and Dad: Did they understood the options available to them? Did they know that if they chose to take me home the work would be hard, overwhelming sometimes? Had they done anything to make the house safer: What, specifically? “Specifically from my end,” she said, looking directly at my mother, “have the guns been locked up?”

“There was only the one gun,” my dad said.

I saw my mom holding herself with what still feels in memory like incredible dignity and grace. Her voice caught but she did not break. Things had been going on in the house while I’d been away, hard conversations.

“We got rid of it,” she said. The social worker wrote something down. Dad took Mom’s hand, there on top of the long table. The questions started up again. I looked out through the window at the road that led from hideous rooms like this to a safe refuge hidden deep in the ground somewhere in Kansas.

They had enclosed pictures of themselves, wallet-size portraits by a high school photographer. Lance was not a new player, but I felt that he was now starting off on a new adventure; I stopped to consider that, what it might mean for him. I guess no matter what your circumstances are you drift at some point from feeling like you’re one of the young people to feeling like some of them could be your own kids. I hadn’t noticed the drift; probably no one does: but I felt my eyes, where most of my expression is concentrated now, beginning to assume that hateful, condescending warmth you struggle your whole life to resist.

In his high school portrait Lance wore a crisp gray blazer; it felt like somebody’d picked it out for him, but it suited his expression, the very intentional seriousness he projected. It was a little big on him; I remembered my mother urging me to wear something nice on picture day every year, a sweet little memory. Lance’s hair in the picture was long and thick, and you could see the fresh brushstrokes running through it where he or somebody else had put it into place just before the sitting. Curls bunched above his ears, playful intruders into the steely look he was trying to give the camera.

Carrie’s picture was in softer light and was set before a cloudy-blue background screen. Her elbows rested on a shelf, and she looked like she was making an effort to hold the pose. Her hair was rusty blonde; it looked dry and brittle, and a little wild. She tried hard to meet the lens directly, but ended up looking like she was staring at something on the other side of it, maybe something way off in the distance: that blank stare people get when they’re thinking too hard about how they’re going to look. I looked at their pictures next to each other, nested against the chaotic give and take of their letter; their faces looked wet. My lips twitched. It was just lamplight on the gloss, of course, or something like that. I started to tell myself a story about it, and then I made a point of not taking the story any further, and I pulled an envelope from a drawer.

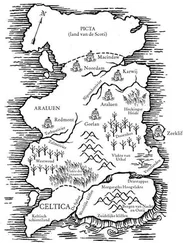

After the guy who invented Conan died a bunch of other people wrote Conan books. Some of them were by people who’d known him when he was alive; others were by fans who had their own ideas. I had a ton of these books. I could never get enough.

I wondered, in the privacy of my thoughts, whether the things that were interesting to me would leave me isolated at Transitional Living, but I didn’t go to Transitional Living. We got as far as the walk-through and a final planning interview at the facility, and then we drove back to the hospital, we three together; there were two days left for me there, formalities. Blood tests, last visits, paperwork. I sensed the gravity of my position when we got back to my room.

“I don’t want to go live with — with those people,” I said after they’d brought me back to my room.

Dad looked at Mom, and Mom looked at me.

“We can’t,” my father said, “take care of you here. At-home here, back at the house. At home we can’t take care of you.”

“I know, Dad,” I said. “I wonder if—”

I hadn’t given any thought at all to what I was going to say.

“Your chair won’t even fit in the main hallway,” Dad said. “We measured.” I pictured Dad with his measuring tape in the hallway, Mom reading numbers to him. I could imagine the look on his face as he worked out numbers in his head, his lips moving maybe, simple math and its consequences. I wondered how much less I weighed now than I had a few months ago.

“I still get physical therapy after I leave,” I said. “I’ll be walking by myself after a while.”

“By the time you’re nineteen, Sean. They say you’ll be walking unassisted when you’re nineteen.”

It would be a long time to keep me at home, I knew.

“If I can find a place to live by myself, will insurance pay?” I said. I had been around for enough insurance talk to understand that this was a big part of my future picture: who would pay for it. How I’d eat. When I asked this question, Dad looked at me like he was looking at a grown-up. I felt proud.

“They would,” he said. “If you can find work, insurance will pay for your care, but otherwise you have to be at home for them to pay. I just can’t see how you find a job with your — with your face — with your face like it is.”

It was the first time either of them had said something so direct about how I looked, about how I was always going to look. Dad’s little pausing stutter only slowed him down a little; I felt impressed with him, proud of him. I wanted to tell him. There was no way to tell him.

“I know I can figure something out if I can just have a little more time at home,” I said, remembering my intensive care bed in the dark, the patterns in the ceiling, the infinity I’d learned I had in my head. I imagined a quiet future in an imaginary world where nothing ever really happened but everything seemed charged with life.

Mom looked at Dad; if she meant to convey any message to him in her look I couldn’t read it.

“We can go home from here and talk about it for a while,” Dad said after a long minute. “We don’t have to decide anything today.”

It was too quiet for everybody. Mom started gathering my books from the cheap nightstand with its floor-scraping wheels. Conan the Freebooter. Conan of Aquilonia. Conan of the Red Brotherhood.

Skulls in the Stars.

They’re riding toward me now. They bear the mark of the captive on their forearms. These are men from a degraded oceanside kingdom somewhere far off, back where I come from, maybe: hunters with no personal interest in their bounty, conscripted into service by want or need. There’re two of them; one gestures toward me, his finger arrow-straight in the oncoming Kansas dawn. He has seen the tangled mass of new growth on my chest. I’m standing there shirtless, wide open, all my weapons long since traded for food or medicine, corn-stubble on the hard winter earth, the thousand kings of the strewn territories as good as dead, drained, ad hoc leather cuffs tied to sticks swinging saddle-side. They’re coming for me. There is an opening in the ground. I can stand and fight, or I can drop down. I have come too far to let myself be captured.

It was back when I was twenty-three, I think. Maybe twenty-two. From my own perspective my life was unremarkable. The pity strangers visibly felt for me, the unmistakable physical flinches they gave off on seeing me, were like map markings suggesting some present horror. But in my own eyes I was normal. Here and there, alone, reflecting, I’d bump up against what felt like a buffer zone between me and some vast reserve of grief, but its reinforcements were sturdy enough and its construction solid enough to prevent me from really ever smelling its air, feeling its wind on my face. There must be others like me who struggle more than I do. It makes me sad to think of them.

Читать дальше