Besides the bees, the painting, the carpentry, and his accomplishments as a handyman — he made birdhouses, he kept tropical fish — he had a great assortment of simple weapons: air guns, slingshots, crossbows, throwing knives. And much more: a suit of armor, a blunderbuss, a working cannon, shields, spears, a collection of war clubs from various Pacific islands. In the room that served as his arsenal, he also had a wind-up phonograph and a jukebox.

"What do you want to hear?"

"What have you got?"

Pressing buttons, he said, "Here's a favorite of mine."

It was Frank Sinatra singing "Blue Moon."

"That was very popular when I was at school."

That was how I got an idea of his age.

"Did you grow up with guns like this?"

"Oh, no," he said. "My mother hated guns." He paused, smiling at the music or a memory. "Hated rock-and-roll too." He looked around the room and said with pleasure, "This would have appalled her."

I understood him better then. These were things he had always wanted, that he had finally attained. It was really very simple. He didn't yearn for "Rosebud" — he possessed it and had all the time in the world to enjoy it.

I never saw him angry or drunk or depressed. He had the patience of a Buddhist monk. He was modest; I never heard him boast. He was compassionate and kind, and he yearned for nothing. His staff loved him. I

liked being with him — and, as I say, I always felt better afterward. He gave me confidence and energy. I saw him as one of the lucky few.

But he confounded me. A happy man cannot be the subject of a story. You never saw his sort in a story. Happiness is hardly a subject — Tolstoy said as much in the opening sentence of his hybolic masterpiece. It amazes me that I have written this much about Lionberg, the happiest man in Hawaii.

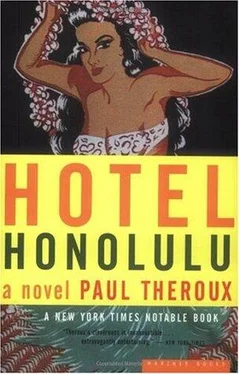

They had agreed that he would be in the Hotel Honolulu lobby holding a copy of Honolulu Weekly, and so would she, but coming up behind the man reading the personals and chewing his knuckles, she hoped he was the wrong one. Her eyes racing, she took him in all at once in desperate scrutiny, looking for something positive, any feature, as if she were trapped in a strange room and searching for an exit. He had not noticed her yet, still he was reading, and she was short of breath seeing the page headed Women Seeking Women.

Perhaps he seemed uglier than he really was because she was so afraid of him. Certainly the instant she saw him sitting there, gnawing the back of his hand, she forgot that she had ever spoken to him. He might well have been a reasonable-looking person, but the moment made him hideous and she could not recapture any of the innocence of her first glimpse. Had her mood, her distorting memory, made him into a monster?

He might have looked like a nice guy — she would not have approached him otherwise — but later, all she could remember was that she had feared him from the first — his size most of all, for he was big, sacklike, with small shoulders, sprawling pillowy hips, weighty legs that seemed even wider because of his baggy shorts, the sort of tightly laced

sneakers that made your feet sweat. His head was tiny and two-sided, exaggerated by a cheap haircut.

His earrings worried her more than almost anything else: he wore one in each ear. Two earrings — what's the deal? was a question she tried to improvise. She wanted him to be the wrong man, not "larc22" from aloha.net but just a fat guy with the Weekly where "larc22" should have been.

His narrow shoulders twitched in premonition, then twisted, and he squinted at her and smiled. Had he just eaten a candy bar? He had parentheses of chocolate scum at the corners of his mouth.

"Aloha, Saddy."

Her heart pinched. She said, "Sadie."

The e-mail name was "Saidy," but she could not blame him for getting it wrong — she had never spoken the word before.

"Daisy, actually," she said. "Are you 'larc twenty-two'?" Only now did she remember his mentioning the Milky Way candy bar he usually ate when watching The Tonight Show. Yet he had also claimed to like scuba diving and said something about riding around the island on his motorcycle. It was easier to imagine him in his room, eating candy and watching TV, and on his shelf the first catcher's mitt he had ever owned and the scattered parts of a turntable he was fixing so that he could listen to his collection of old Hawaiian 78s. She knew everything about him.

"Or should I call you Carl?"

As he had come toward her, walking flatfooted as though tramping through sand, she had stepped backward. She registered that he was heavy but not tall and that he had a hungry smile.

"I spend so much time online, I don't even think of myself as Carl anymore."

Another scary factoid, she thought, that he regarded himself as "larczz," like one of those bulgy-faced robots on Star Trek, the reruns of a show he never missed. He had warned her, I'm a Trekkie.

So that he would not come any closer, she sat down, and he sat too, heaving himself into a nearby chair, seeming like an obstacle.

"Did you come here on your motorcycle?" she asked.

One of his habits — in this minute or so she had established this, had seen him do it twice — was knuckle-chewing. He did it again.

"Sold it," he said. His gnawing made him scowl. "So you want to go somewhere?"

She wanted to go home. But she was fearful of upsetting him by rejecting him so fast. She was already afraid of him and wishing to placate him, so that she could leave and never see him again.

"How about right here?" she said. "There's a bar and a lanai."

Something in his manner made her want to stay in the open with him. She went ahead into Paradise Lost, imagining she could feel his

breath on her neck. She hurried past the booths and made for the outside tables, sitting quickly so he would not touch her.

"I know you don't drink," she said. "But this is a nice place."

"I'm a cheap date." He had made that comment every time he mentioned how he didn't drink alcohol. "But go ahead, have your frozen margarita."

She almost did not order one, to spite him, but the waiter was hovering and listening, and she thought the drink might help her get through this. After a sip of it — he was drinking Diet Pepsi — she said, "Isn't there anything you can do? I mean, is your liver permanently damaged?"

"Stays fried," he said, and explained his hepatitis once more, how he had contracted it on Maui one New Year's.

I cannot believe I'm having a conversation with this strange man about his liver, she thought. In her mind she saw a purplish piece of raw liver on a white dish.

"So are you still getting those dizzy spells?"

"I just told you I am," he said.

She hadn't been listening. He had been describing his ailments while she had been abstracted thinking of them. To hide her face, she lifted the wide margarita glass and sipped.

"I really hate him."

"Who?"

"Jimmy Buffett."

She knew that. She just hadn't made the connection. He hated the Grateful Dead, too. He liked Hawaiian music and Philip Glass. So did she.

He liked scuba diving. She was certified. And motorcycles. She had imagined herself a passenger on his. But I hate these macho bikers, he had once said to her. From that remark she took him to be small, perhaps delicate, slender anyway, and saw him somehow in light slacks and sandals and a fluttery aloha shirt. But no, you could hate machismo and still be a big soft spud with two earrings.

"So how's the diving?"

"I haven't been lately. We usually go to the North Shore."

She knew that, too — Haleiwa Beach Park, with his friend Mickey.

"Wetsuit's shredded. Have to get them specially made. Credit card's maxed out."

His manner of speaking was so like one of his e-mails that she smiled and absent-mindedly touched her forearm.

Читать дальше