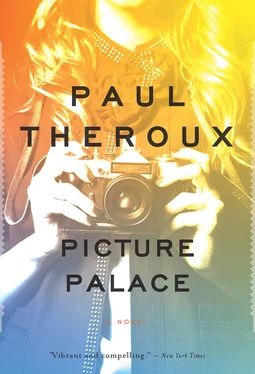

Paul Theroux

Picture Palace

From the first moment I handled my lens with a tender ardor, and it has become to me as a living thing, with a voice and memory and creative vigor.

— Julia Margaret Cameron, “Annals of My Glass-house”

ALL DAY LONG I had been thinking that I had grounds for believing I was an original. A beautiful day.

Now the light was failing, and the old house had that late-evening fatigue that followed a scorcher, a kind of thirst aggravated by crickets: groans from the woodwork and all the closets astir. Beyond the windmill the moon on white fence-posts made tracks to the shore of the Sound. The rest of the Cape was dark, yet I would not have been anywhere else. Blind love? It was an old feeling in me. It made me a photographer.

Some people thought I began in the wet-plate days. No — and I did not invent the camera, though a fair number of admirers told me I was the first to make it work properly, not only with Boogie-Men , my early negative prints, Pigga, Negro Swimming to a Raft , and Blind Child with Dead Bat , but in the simpler Clamdiggers: Wellfleet and the very steamy sequence of the Lamar Carney Pig Dinner. Firebug, Fidel at Harvard , and my portrait of Ché Guevara were part of the folklore. As for your favorite, Twenty-two White Horses— that received more attention than it deserved: it is seldom one’s best work that brings one fame. But I was still proud of Orthodox Jewish Boys, Cummings in Provincetown, Refugees, Danang , and Marilyn .

“I’ve never seen Marilyn like that before,” a critic once said to me.

“That’s not Marilyn,” I said. “It’s a picture.”

There were many more. Where was I? A barnacle named Frank Fusco told me that laid end to end in a retrospective they would tell my complete story.

I said, “Just because I happen to be a photographer, it doesn’t mean I have to make an exhibition of myself.”

“I want to hang your pictures,” said Fusco.

“Hang them!” I threw open the windmill, my picture palace. “Hang them until they’re dead!”

I was posturing; I still believed in my pictures. And what a posture! Your Walter Mitty dreams of heroism and great deeds. This is not odd, but most heroes and doers I have known dreamed of being Walter Mittys — puzzled benumbed souls with sore teeth and eyeglasses, shuffling through the house in carpet slippers to take a leak. “What’s all the fuss about?” says the American creative genius. “I’m just a farmer.”

For over fifty years I was a world-famous photographer, but being a woman was regarded as something of a freak. “A credit to her sex,” the patronizing critic often said, calling attention to my tits, which they promptly put in the wringer of art criticism.

But art should require no instrument but memory, the pleasurable fear of hunching in a dark room and feeling the day’s hot beauty lingering in the house. No photograph could do justice to these aromas. And gin and solitude — drawing the cork and decanting the clear liquid and tasting it to hear the ghosts wake in the walls. A camera was, after all, a room.

As a photographer I considered my camera indistinguishable from my eye. It was my Third Eye, as close-fitting as a jeweler’s loupe, almost corporeal. My life was in my pictures. With so many loyal subjects it was easy for me to believe that I was a queen.

Frank had begun to forage in the windmill for the Maude Coffin Pratt Retrospective. I had no reason to discourage him. It was not until I tried to do Graham Greene in London that I had doubts about the whole shooting-match.

IT WAS something of a struggle, getting away from Grand Island (which is not an island, but a “neck”—a South Yarmouth sandbar in Nantucket Sound). No one wanted me to go: afraid I’ll croak, barf on my shoes, faint on the plane, get lost, disgrace myself — that sort of elderly caper. My eye! Of course no one admitted it. They said, “Watch out, Maude — he’s got a reputation,” laying it on thick with that leering insincerity the younger set uses on old ladies. They want to keep us indoors, so they get flirtatious and start the canoodling routine. They are supposedly flattering me by treating me like a fairy’s mother, one of those grasping disappointed women who like to be kissed and winked at and warned that they might be in for a little unwanted boom-boom.

I said sharply, “Listen, I don’t think a seventy-year-old has much left to fear, do you?”

“Sure, he’s all right, but what about you, sugar?”

Nudge, nudge; you can’t win. They’re really saying: Forget it, stay home, frig around with your old prints, leave everything to us; your career is ours now. Kind of a denunciation, and it peeved me.

It was about this time that Frank Fusco came up to the Cape from New York and asked me would I consider a Maude Pratt Retrospective and let him use my “archives,” as he called the crates of photographs in my windmill. May we hang you?

I could not refuse. I do not enter that windmill. And Frank was eager. A tetchy too-skinny bachelor, thirty-odd, Frank seemed to me one of those barnacles of the arts who is more tenacious than any practitioner. He called himself variously a collator or curator or an archivist, but I knew he would flourish tight against my decayed timbers, prove himself my benefactor and show me the value of my bulk. As unobtrusive as a thief and with the same ability to conceal the fidget in his gestures, he was helpful, secretive, unreadable, at my service and irritating in a way that helped me think straight.

“Why bother?” he said when I told him I had been asked to photograph Greene. But I thought: Why not? The Greene portrait could be the last one in the exhibition, a celebrated artist, my own vintage. It would be a fitting end to my career. I could then quietly die — or as Papa said, “leave the building”—with the certainty that I was really done.

The story was that Greene would only consent to a portrait if someone like me did it, a point of view I could well understand, since I would only consent to do a portrait of someone like him. The photographer at the frontier of her profession poses no problems to the distinguished subject — no danger, no indignity; nor does the beginner, who doesn’t mind being bullied and condescended to. I know: it was for this reason that, at a fairly young age, I was able to photograph Alfred Stieglitz. But somewhere in between are the ones we’ve learned to avoid, the hookers and fame-suckers of the trade who want to take you over. Photographers are the worst — they want to marry you, move in, flush your achievement down the tube or gobble you up. The young lady chronicling with her camera is out for blood; young men, too. And they’re not attracted by the work. It’s the cult of personality they want to glom onto. It’s a free country: Why can’t I be you ? At my age, I find them an annoyance rather than a threat, but I felt in all modesty that Mr. Greene needed me.

Frank was opposed to my going. He narrowed his eyes at the windmill and said, “I could use your help in there.”

“Not on your tintype,” I said.

“And I don’t think you should be traveling.” He shook his head and made a cringing appeal, a funny little pitying noise at the back of his throat that meant at your age . “I mean, to Yerp.”

“You don’t think I’m up to it?” Yerp!

“I didn’t say that.” he said hoarsely, backing away. “It just seems kind of, um, precipitate.”

“Whip it out,” I said.

Читать дальше