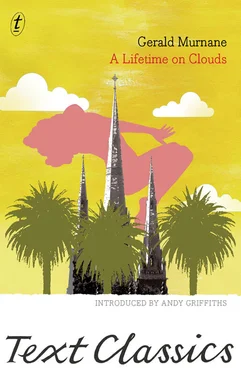

Gerald Murnane - A Lifetime on Clouds

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Gerald Murnane - A Lifetime on Clouds» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, Издательство: Text Classics, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Lifetime on Clouds

- Автор:

- Издательство:Text Classics

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3.5 / 5. Голосов: 2

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Lifetime on Clouds: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Lifetime on Clouds»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Earnest and isolated, tormented by his hormones and his religious devotion, Adrian dreams of elaborate orgies with American film stars, and of marrying his sweetheart and fathering eleven children by her. He even dreams a history of the world as a chronicle of sexual frustration.

A Lifetime on Clouds — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Lifetime on Clouds», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘And what do we find? This year, 1954, we had twenty-three ordinations. That’s just six more than in 1944. You can see we’re not really keeping up with the demand for priests. It’s been calculated that we need a minimum of fifty to sixty ordinations each year until 1960 just to properly staff the parishes we’ve already got and keep some of our overworked priests from cracking up under the strain. Our team is up against it. We’ve got our nineteenth and twentieth men on the field and we’re fighting overwhelming odds. The coach is crying out for new recruits. And this brings me to the point of my little talk to you.

‘Theologians tell us that God always provides enough vocations for the needs of His Church in every age. In others words, this year all over Melbourne God has planted the seeds of a vocation in the hearts of enough young men to meet the needs of our Archdiocese. But God only calls — He never compels. So if we find next year an insufficient number of candidates entering our seminary, we can only conclude that a great many young men have deliberately turned their backs on a call from God.

‘And now I’m going to speak bluntly. Bearing in mind the needs of our Archdiocese at present, I would say that each of the major Catholic colleges (and this includes St Carthage’s of course), that each of them should have at least ten boys in the matriculation class this year who’ve been called by God to be priests in the Archdiocese of Melbourne. Next year most of you chaps will be in matric and the same will apply to you. Which means there could well be ten of you listening to me now who’ve already been called, or will soon be called by God, to serve Him as priests.

‘To have a vocation to the priesthood, a boy needs three things — good health, the right level of intelligence, and the right intention. Good health means an average constitution strong enough to stand up to a lifetime of hard work — you all look to me as if you’ve got that. As for intelligence, any boy who can pass the matric exam (including a pass in Latin) will have the intelligence to cope with the studies for the priesthood. Health and intelligence are fairly easy to judge. The third sign of a vocation is the one you have to be really sure of.

‘A boy who has a right intention will first of all be of good moral character. Now this doesn’t mean he has to be a saint or a goody-goody. He’ll be a good average Catholic boy who’s keen on football and sport and works hard at his studies and doesn’t join in smutty conversations. Of course he’ll have temptations like we all do. But he’ll have learnt how to beat them with the help of prayer and the sacraments. And as for the right intention, well, it could be the desire to win souls for God — to give up your whole life to do His work.

‘An example of a wrong intention would be, for instance, to want to be a priest as a way of advancing yourself in the eyes of the world. But thank God in these days it’s very rare for anyone to offer himself for the priesthood for reasons like that.

‘And that’s really all there is to it. If you have good health, the right level of intelligence, and a right intention, you’ve almost certainly got a vocation to the priesthood. The trouble is, too many young fellows think they have to get a special sign from heaven. They expect an angel to tap them on the shoulder and say, “Come on, son, God wants you for a priest!” Or perhaps they think they’ll have a vision some morning after mass, and see Our Lord or Our Lady herself beckoning to them. Nonsense! All the priests I know have been thoroughly normal young chaps like yourselves who realised one day that they had all the signs of a vocation. Then they prayed and thought about it and talked it over with a priest and that was that.

‘Sometimes a fellow can realise he’s got a vocation in funny ways. One of our outstanding young priests always maintains he got his vocation at a dance. It seems he was standing in a corner watching all the happy young people enjoying themselves around him when he suddenly realised that all this was not for him. God was calling him all right, and compared with the life of a priest, all the pleasures of the world seemed worthless.

‘Some men say they knew from the time they were small boys that they had a vocation. Others never realise it until they’re grown men — sometimes years after they’ve left school. The idea that God is calling you can grow on you slowly or it can hit you like a flash of lightning. There may be someone in this room right now who has never before asked himself this simple question, “Is God calling me to be a priest in the Archdiocese of Melbourne?” If any one of you is in this position, it might be a good time now when you’re approaching your last year of school, and wondering what you’re going to do with your life — it’s a good time to ask yourself seriously and honestly, “Is God calling me?”

‘Boys, would you each take a pencil and a piece of paper and write down something for me. For the sake of privacy I must ask you all to write something. If you can say in all honesty that you definitely don’t have a vocation to the priesthood, just write “God bless you, Father,” or something like that on your paper and don’t put your name. If you’re at all interested in the priesthood, just sign your name and write the word “Interested”.

‘Those who are interested can have a chat with me in the brothers’ front parlour some time today. I’m not a salesman, remember. No priest would ever dare to put pressure on a boy in such a serious business as this. If you care to have a chat with me I’ll arrange to send you some literature and leave you my phone number if you want any further advice from time to time.

‘Now would every boy write on his paper and fold it up small and pass it to the front, please.’

Adrian wrote, ‘Definitely interested — Adrian Sherd’. He folded his paper and passed it forward. Then he sat back and told himself he had just taken the most dramatic step of his life. But then he remembered you couldn’t make a decision as important as this without a lot of prayer and thought. Yet the young man at the dance had decided in a flash that he would give it all up. (Some of the girls in their ballerina frocks would have been almost as beautiful as Denise McNamara.) And now that man was an outstanding young priest and the girls were all happily married to other chaps.

Soon after lunch a message came for a certain boy to see Father Parris in the brothers’ parlour. The whole class watched him get up from his seat and go. They were not surprised — he was quiet and solemn and he objected to hearing dirty jokes.

Adrian waited for his turn to visit the priest. He was worried about Seskis and Cornthwaite and O’Mullane seeing him leave the class. He saw them putting up their hands and saying, ‘Please, Brother, Sherd can’t talk to the vocations priest — last year in Form Four he committed nearly two hundred mortal sins.’

Father Sherd stepped up to the pulpit to begin his first sermon in his new parish. He saw the three of them grinning up at him from the back seats. They were ready to heckle him with shouts of ‘What about Jayne and Marilyn?’ They had already sent an anonymous letter about him to the Archbishop.

But God would keep their lips sealed. He would never allow one of His own priests to be reproached in public for sins that had been forgiven years before. And how could Seskis and the others speak out without revealing their own guilty secrets?

When it was Adrian’s turn to leave the classroom, he stood up boldly and strode to the door and silently offered up his embarrassment as an act of reparation to God for the sins of his past life.

Adrian said to the priest, ‘My story is probably unusual, Father. When I was at primary school I served as an altar boy for years and developed a great love for the mass and the sacraments and often wondered whether I might have a vocation to the priesthood. But I’m sorry to say a few years ago I fell among bad companions and had a bit of trouble with sins of impurity — not with girls, fortunately, but on my own — mostly thoughts, but sometimes, I’m sorry to say, impure actions.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Lifetime on Clouds»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Lifetime on Clouds» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Lifetime on Clouds» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.